In Everett, Washington, Jasmine Vandelac awakened one morning to discover that someone had ransacked the Honda Odyssey minivan and Toyota Tacoma truck parked in her driveway and made off with her husband's electric guitar. Vandelac has security cameras mounted around her home, but when she watched the video from around 2 a.m., she was puzzled.

"It was a group of four men who came down the driveway at the same time," she recalls. "Each went to a different side of the vehicles. Then one man took something out of his pocket — it looked to be about the size of a cell phone — and aimed it at the cars. Then, instantly, the lights went on and all four doors opened."

Vandelac is sure that both vehicles were locked. Nevertheless, the thieves apparently were able to open the vehicles' keyless-entry systems as readily as if they'd been using the smart keys that she says were inside her home.

The still-unsolved theft is just one of numerous reports over the past year, in locales ranging from Sausalito, California, and Yukon, Oklahoma, to Saginaw County, Michigan. Criminals are gaining entry to parked cars, apparently by tricking their keyless-entry systems into unlocking the doors.

None of the perpetrators have been caught, and the gadgetry they are using remains mysterious. But some electronic security experts believe that the criminals may be exploiting the convenience of keyless-entry systems, which are designed to detect and authenticate the smart key inside a car owner's pocket as he or she pulls on the door handle. They say that if the thieves can amplify the car's signal (a "relay attack," in electronics lingo) it can be fooled into using the owner's key to open the doors, even if that key actually is on a nightstand or the kitchen table inside the house.

But the vulnerability doesn't stop with the doors. European researchers actually have used the same sort of electronic trickery to start cars' ignitions and drive them away — though fortunately, thieves haven't followed suit. At least not yet.

The hacking of keyless-entry systems is so new that there isn't yet any reliable data on how often it is occurring, says Carol Kaplan, director of public affairs at the National Crime Insurance Bureau, an industry organization that tracks auto thefts and break-ins.

"But we hear increasingly from law enforcement agencies that we work with that there are more and more cases like this," she says. "One problem is that it's very hard to prove that a car has been broken into by using this method. There's no evidence left behind, no broken glass or scratches on your car. All you know is that you come back, and your stuff is gone."

This video from the bureau includes surveillance footage of some thieves using the devices.

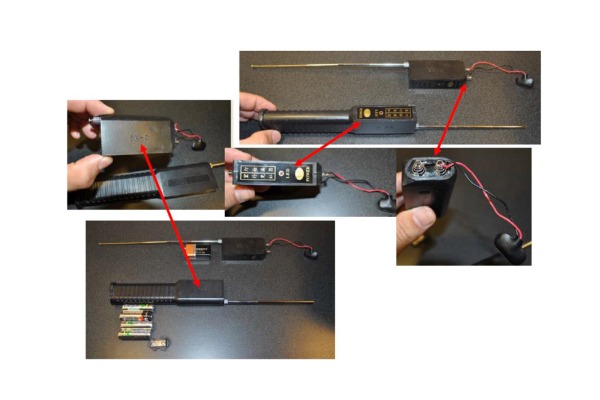

Kaplan says that one law enforcement agency, which she declined to identify, actually has obtained black-market devices used in such thefts. She described one of the devices as looking "like a transistor radio with an antenna."

On the academic front, a trio of researchers demonstrated the vulnerability of keyless-entry systems to relay attacks in 2011. The researchers from ETH Zurich, a Swiss technology and engineering university, presented a paper at a security conference that described a method for defeating the keyless systems in 10 vehicle models from eight different makers. They not only unlocked the doors but managed to drive away, even though the smart keys were no longer nearby.

"Cars will never stop the engine if the key is not detected anymore," one of the researchers, Aurélien Francillon, explains in an email. Instead, "they will show a warning on the dashboard or they will emit a warning sound."

Francillon, who sometimes assists law enforcement agencies, says he's convinced from information he's seen that European thieves are using relay attacks to steal cars outright, using electronic signal-amplifier devices manufactured in Eastern Europe and Germany. "Maybe it's just a question of time before they get used in the USA," he says.

The prospect of thieves being able to exploit keyless-entry systems, and what countermeasures might be needed to stop them, is something that the auto industry doesn't seem to be eager to talk about. Several automakers whose vehicles reportedly have been broken into by gadget-wielding thieves didn't respond to requests for comment. The Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that represents 12 major brands, provided a statement by email in which it said that automakers "have been working on multiple fronts to address the security of their products."

According to Francillon, it's not going to be easy to fix the vulnerability. The problem with current keyless-entry systems, he says, is that they don't actually measure the distance between the key and car, but instead assume that the key is close because its radio signal is detectable. Actually measuring the distance would require manufacturers to switch to a different radio technology, Ultra Wide Band (UWB) 9.

"It uses very short radio pulses, which allow it to measure the time at which signals arrive, very accurately," he explains. Manufacturers also would need to beef up their cryptography.

Other experts question whether those upgrades really are warranted, given that relay attacks aren't yet being widely used by thieves, in part because they require too much technical expertise compared to the array of proven low-tech methods for breaking into cars or stealing them.

"Compare it to breaking a window, or driving up in a tow truck and hauling the car away, and it's a lot more complicated," says David Wagner, a professor of computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, who has studied the cryptographic systems used in keyless-entry systems.

For car owners who want to protect themselves against keyless-entry hacks, though, experts say there are precautions you can take.

Stefan Savage, a University of California, San Diego computer science and engineering professor and a staffer at the Center for Automotive Embedded Systems Security, says that keeping your keys in a metal box, or carrying them in a wallet or purse designed to thwart hacks of passports with radio-frequency ID chips, could do the trick. Some key-holder products that claim to act as effective Faraday cages are the Fob Guard pouch and cases or wallets by Silent Pocket.

If you're really worried, he says, you could stick the key in the refrigerator, whose exterior would block signals. But a downside to storing keys in the refrigerator (or the freezer, another location that some security experts have suggested) is that doing so may harm lithium batteries. They are meant to be stored at about 68 degrees Fahrenheit: far above refrigerator and freezer temperatures, according to standards set by the National Electrical Manufacturers Association.

It may be that simply adding additional layers of security (such as parking your car in a locked garage or in a well-lighted place) could deter technologically savvy thieves, just as it would ones who employ more brutish methods.

But even if relay attacks aren't yet a major menace, they might be a harbinger of a future in which thieves increasingly try to attack the electronic and wireless gadgetry that has become an integral part of automobiles. A recent article on Wired.com described a more complex method demonstrated by Australian security researcher Silvio Cesare. He reportedly used a laptop computer and a radio transmitter to bombard a keyless-entry system with thousands of guesses about its authentication code, until he hit upon the one that would unlock it.

Researchers have exposed other vulnerabilities in automotive cryptography as well. Wagner says he's concerned about the future prospect of hackers breaking into cars' electronics via the Internet and seizing control of them for extortion purposes — a racket similar to the ransomware that some use to infect unwary PC users. "We haven't seen that yet," he says. "But that would be my real worry."