Women represent about 51 percent of the population in the United States, but having a slight majority in the population did not make it any easier for them to be considered in crash testing. Up until recently, only average-sized adult male dummies were used in crash testing, which meant that effects of auto crashes on women, particularly petite women, were not studied. But as automobiles and the safety systems in them became more advanced, the size of the occupants suddenly became more important and researchers saw the need for dummies of other sizes. Since 2000, both the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), have used female dummies in various crash tests, yet each group takes a very different approach to its use of the female dummy in crash testing. We talked with both organizations, which are the two groups that conduct crash testing in the United States, to learn about their approaches, why they are different and what it means to today's female drivers.

Good Ol' Boys

Back in 1978, when NHTSA first began its crash test program, automobiles were very different. Airbags, and even three-point seatbelts, weren't commonly found in cars. Dr. Rolf Eppinger, chief, National Transportation Biomechanics Research Center at NHTSA, explains, "Before the agency [NHTSA] mandated airbags and seatbelts, the use of the 50th-percentile male dummy was considered sufficient to provide an evaluation of the performance of safety belts for the entire driving population, even if each possible size wasn't tested." This dummy, called the Hybrid III, is still in use by both NHTSA and the IIHS today. An average-sized adult male, the Hybrid III dummy weighs in at 170 pounds and is 5 feet 9 inches tall.

As airbags were developed, it became obvious that the effects of these safety systems, what Eppinger calls "safety performance," varied widely depending on the height and weight of the occupant, especially if that occupant was in the driver seat. "Smaller females, and small males, too, tend to sit closer to the steering wheel and thus have a greater chance of interacting with and being harmed by the rapidly deploying, unfolding airbag," says Eppinger.

Boy Meets Girl

As researchers began to realize the issues that people of differing sizes would face, they started to look at developing dummies that would represent the smallest and largest adults. In the mid-1980s, researchers developed a dummy representing a 95th-percentile male, who was larger than 95 percent of the adult male population, and a 5th-percentile female dummy, who was smaller than 95 percent of the adult female population. Both of these dummies are versions of the Hybrid III dummy that have been scaled up or down. The 95th-percentile male is 6 feet 2 inches tall and weighs 223 pounds, while the 5th-percentile female is 5 feet tall and weighs 110 pounds.

While the 5th-percentile female Hybrid III dummy was put to work immediately in frontal crash testing within the automotive industry, she was not used for U.S. safety regulations until the year 2000. There, she is used by NHTSA to "evaluate the out-of-position performance of inflating airbags as well as the performance of a normally seated female driver and passenger at crash speeds of 20, 25 and 35 miles per hour," says Eppinger.

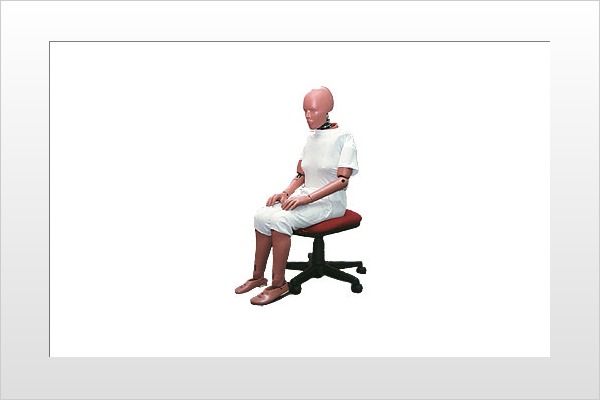

Like all adult crash test dummies, the 5th-percentile Hybrid III female dummy is designed in a seated posture that can be adjusted to create realistic driver and passenger seating positions, including both restrained (wearing a seatbelt) and unrestrained. She has a range of motion similar to a human, so researchers can assess the way her body moves during crash testing. Multiple tests are conducted that allow researchers to study her movement in a variety of seating positions, with and without her seatbelt and with and without the airbag deploying.

In frontal crashes, most small women tend to sustain injuries to the neck when they are in what Eppinger calls "out-of-position" crashes, essentially due to women sitting much closer to the steering wheel — and the airbag — than the average or tall driver, or by not wearing a seatbelt and being propelled forward in a crash. This was a much larger issue in the 1990s than it is today, before federal regulations led to the development of depowered and multiple-stage airbags. "Airbags deploy at very high velocities, sometimes over 100 miles per hour, and certain designs can potentially harm people who come in contact with them during the unfolding phase of their development," explains Eppinger. Since 1990, when airbag deaths were first tracked, there have been 95 deaths of adults who were either the driver or front-seat passenger. That number has declined dramatically in the last few years, with nine adult deaths recorded between 2001 and October 2004.

While vehicles with depowered airbags reduce this risk dramatically, some women still fear being hurt by their airbag in a crash and consider disabling it. Both NHTSA and the IIHS say that this would be far more dangerous than leaving the system enabled. "It's definitely not a good idea to disconnect your airbag. The chances are far greater that you'd be injured in a crash without the airbag than you would by the airbag itself," says IIHS chief operating officer Adrian Lund.

Rather than disconnecting the airbag, Eppinger advises to "set the seat back as far as possible to maximize the distance between the steering wheel hub and the forward surface of the chest without compromising your ability to drive the car." Lund adds, "Ideally, you'd want to be at least 10 inches away from the steering wheel."

She Has a Sister

While the 5th-percentile Hybrid III female dummy is useful for front crash testing, her body is not built for side crash testing, so a "sister" dummy was created for this use. SID II(s), which stands for Side-Impact Dummy, version two, small, is also representative of a 5th-percentile female. Like her Hybrid III sister, she is also 5 feet tall and weighs 110 pounds. This dummy is a derivative of the original SID, a 50th-percentile male dummy that was developed in the late 1970s by NHTSA. Because humans who are in a side-impact-type of collision are likely to suffer different types of injuries than those in a front-end collision, side-impact dummies have ribs and a spine that flexes differently in a crash. They are built specifically so that researchers can measure the risk of injury to the ribs, spine and internal organs, such as the liver and spleen.

SID II(s) was built as a special project by a group of researchers working with a group of automakers. Currently, she is only being used in the side-impact testing conducted by the IIHS, although NHTSA is considering a proposal to put her into use in its program. The IIHS began using her in its early developmental side-impact testing in 2000 and now uses her in all its side-impact crash tests both in the driver seat and in the rear seat behind the driver. "The 5th-percentile female is also similar in size to the average 12- or 13-year-old child, who is most often in the rear seat," explains the IIHS' Lund. "This allows us to measure the potential of injury to those youngsters as well."

The issue affecting small-statured adults and older children is the same. In both instances, the shorter height of these vehicle occupants leads to a greater likelihood of head and neck injury than taller occupants. "Smaller drivers usually have shorter legs and tend to move the seat forward so their head is in front of the window (instead of at the B-pillar — the metal pillar where the seatbelt is mounted). Older children's heads are frequently also next to the rear window. In both cases, there is a much greater risk of head injury from intrusion of another vehicle during a side-impact collision," says Lund.

Her Day at the Office

A typical day at the office for either the Hybrid III or SID II(s) dummies means a whole lot of abuse before any crash testing begins. Her head is detached and dropped to check that it bounces correctly. Her head and neck are swung from a pendulum and then stopped suddenly to ensure that her neck bends properly. Heavy weights hit her in the chest to double-check that the steel ribs bend the way they are supposed to on impact.

Once the tests are complete, she is dressed in a yellow T-shirt, yellow shorts and yellow shoes. She's then covered with greasepaint that allows researchers to see which parts of the vehicle the dummy collides with during the crash. Yellow and black circular stickers, called "target stickers," are applied to both sides of the head to provide the researchers with reference points when they review the taped footage of the crash in slow motion.

When it's time for the crash test, her real work begins. Sensors all over her body measure the force of the impact and are recorded in a device inside her chest. During the typical crash, which lasts between 100 and 120 milliseconds, her sensors will record over 31,000 pieces of data. After the collision, the dummy's work is done, but the researcher's work is just beginning. The data from the dummy is downloaded into a computer and researchers analyze it to assess the potential of injury a human would have in the same type of crash.

No Average Woman

There is no such thing as an "average woman" when it comes to crash testing. While it would seem logical that if there is a 50th-percentile male crash test dummy, there should also be a 50th-percentile female, researchers at both NHTSA and the IIHS say that there would not be that much difference in the test results of these two.

The IIHS, however, does think there might be some merit to having a 50th-percentile female dummy for rear-impact crash testing. While the risk of serious injury or death is relatively low in a rear-impact crash compared with other types of crashes, there is substantial risk of neck injury, what is known as whiplash, during these types of crashes. Because the position of the head restraint in relation to the occupant's head is crucial to reducing and even preventing whiplash, even the height difference between an average-sized adult male and an average-sized adult female could mean a substantial difference in risk of injury.

"For rear impact, I'd prefer to have a 50th-percentile female for testing. We have talked about this, but it's not something that has gone anywhere yet," says Lund. While it may sound like an easy thing to build, "it's not just a matter of scaling," explains Lund. A new crash test dummy, even one that is derived from an existing dummy takes years to develop to a point where it can be used in formal crash testing. Plus, the dummies themselves are not cheap — about $150,000 for a fully instrumented dummy that is used in testing.

The Pregnant Dummy

There is one more situation where men and women simply can't be compared — when a woman is pregnant. And when it comes to auto crashes, pregnant women, especially those in late pregnancy, are at particular risk. According to research by Dr. Harold Weiss published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, car crashes are the number-one cause of injury death among unborn babies. While there has been some experimenting to create a crash test dummy that simulates a woman in late pregnancy, no "real" dummy has been successfully built.

For the last several years, however, safety engineers at Volvo have been working on a "virtual" pregnant crash test dummy. "Linda," as she is called, is a computer-modeled dummy of an average-sized woman late in pregnancy. She is 5 feet 4 inches tall, weighs about 150 pounds and is in her 36th week of pregnancy. "It is difficult and perhaps even impossible to build a physical model with as much detail and accuracy in human tissue response as we have in Linda," says Laura Thackray, a biomechanics and crash simulation engineer at Volvo Cars Safety Center, who developed Linda. "Additionally, if a physical model was to be made, with realistic tissue responses, it would likely be destroyed after a single crash…. Our computer model can endure as many crashes as we'd like — at any severity level," she explains.

As a computer model, Linda is a combination of a real human body and the Hybrid III crash test dummy. Her "human" components include humanlike tissue in her lower torso, abdomen and upper thigh areas as well as ribs, pelvic bones, uterus, placenta, amniotic fluid and a 36-week-old fetus. These items are crucial to the results of Thackray's virtual crash tests because, in a real accident, a pregnant woman's thorax and pelvis are restrained by her seatbelt, but her abdomen is free to move as a result of the impact. As a result, injuries to her unborn child occur either by the placenta becoming partially or completely detached or, in rarer instances, from the child getting injured from an impact into the mother's pelvic bones or the car's interior.

By using a virtual dummy, the model can be easily scaled up or down to simulate women of different sizes. Volvo researchers are studying how the seatbelt moves; the influence of the seatbelt, airbag and steering wheel on the uterus, placenta and fetus; and how the baby moves in relation to the mother's body. It can also be used to test new designs for seatbelts and other safety systems. "From the simulation results with Linda and the ergonomic studies performed here, I'm certain that there's potential for further development of today's safety systems, especially the safety belt, to provide optimized usability and protection for pregnant women," says Thackray. "In doing so, I think that other occupants will benefit by the solutions."

Thackray has conducted a variety of frontal impact crash tests with Linda in the driver seat, some of which have been similar to the standard frontal crash tests currently conducted by NHTSA and the IIHS. "The tests we've run so far include with and without the airbag, with the steering wheel at various distances from her belly and with the seatbelt worn correctly and incorrectly, as well as not at all," she says.

While it is still early in testing, the results clearly correspond with real-world crashes — that when the seatbelt is worn, and in the correct location, both the mother and her unborn child have a significantly higher chance of escaping injury. Volvo's testing, however, indicates that it is critical the seatbelt be worn properly. Thackray explains, "The belt should fit close to the body, with the diagonal section between the breasts and the side of the belly. The lap section should lay flat and as low as possible under the belly. It must never be allowed to ride upward."

While computer modeling sometimes leads to actual crash testing in a lab, it is unlikely that a "real" pregnant dummy will ever replace the virtual version. Thackray says, "We [Volvo] feel that computer models are far more accurate at modeling human tissue than today's physical models."

Staying Safe in a Crash

Being in an automobile crash is always a scary experience, but there are some things you can do to help reduce the likelihood you are seriously injured.