Update: In November 2007, the U.S. Department of Transportation announced a federal proposal to make school buses safer by requiring higher seat backs and setting new seatbelt standards for the nation's 474,000 school buses. The proposal was approved in October 2008, but all sections of the new safety standard will not be in full effect until 2011.

Should children use seatbelts on school buses? Think this is a no-brainer? Not so fast. Some experts say yes, others say no, and the government's highway safety agency hasn't been able to make a decision.

The government agency involved, the National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration (NHTSA), invited all points of view to be heard at a roundtable in July 2007. Here's what we found out:

Safest Form of Transportation

First, school buses, the big yellow variety, are incredibly safe. According to NHTSA, of the 23.5 million school children who travel an estimated 4.3 billion miles on 450,000 yellow school buses each year, on average, six die in crashes. At the summit, Secretary of Transportation Mary Peters asked, "How can we make this number lower still, so that no parent ever has to hear...that the cherished child they sent off in the bus...is never coming home...even if it requires opening up old decisions and challenging old assumptions?"

In 2002, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) found an additional 815 fatalities related to school transportation per year. But here's the difference: 75 percent of those school children were traveling in passenger cars, not school buses, and just over half of those were teenagers driving themselves to school. Another 22 percent of the 815 fatalities occurred during walking and bicycling. Only 2 percent were school bus-related — referring to children who were hit by buses.

Robin Leeds, spokesperson for the National School Transportation Association, which represents private school bus contractors, says, "The focus on seatbelts ignores the fact that we lose 800 children going to and from school in some other mode. Our challenge is not to make kids in school buses safer. Our challenge is to make kids safer, and the way to do that is to put them in school buses."

Can Buses Be Made Safer Still?

Fatalities aren't the only measure of safety. A NHTSA crashworthiness study of large school buses found that properly used lap/shoulder belts would mean fewer head injuries compared to unbelted passengers. (Lap belts alone, though, showed some potential to cause head and spinal injuries to young children.)

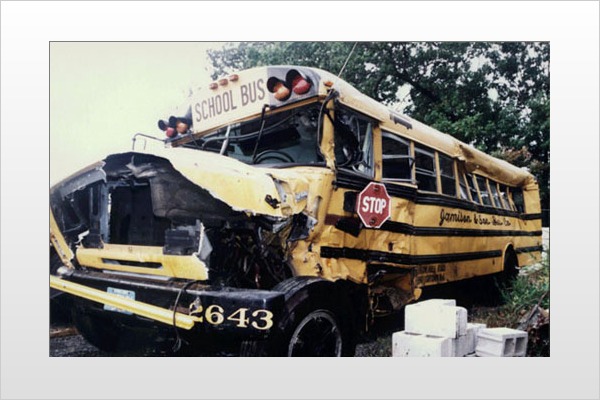

In 1977, federal regulation mandated that large school buses must have strong, closely spaced seats with energy-absorbing seatbacks, a built-in protection called "compartmentalization" that is based on the way crash forces are distributed. The buses were exempted from carrying lap belts. But the government required that small buses (with a gross vehicle weight rating of 10,000 pounds or less) carry lap belts, because the design and weight of the smaller vehicles would not offer protection similar to large ones. (For a dramatic illustration of how compartmentalization, lap and lap/shoulder belts differ, see the crash test dummy video above.)

Despite these measures, government accident studies from the 1980s say that passengers are still endangered in large school buses when they crash with an even bigger or heavier vehicle, such as a loaded tractor-trailer truck, or if they roll over an embankment.

Is the Government Doing Enough?

Seatbelt advocates accuse NHTSA of foot-dragging and relying on compartmentalization to keep kids safe.

Dr. Phyllis Agran, spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics, says, "Data in real-world crashes comparing seatbelt use versus compartmentalization only do not exist. But compartmentalization is a 30-year-old standard that belongs at the Smithsonian."

Using data on emergency room visits, her organization believes there are 17,000 school bus injuries annually versus the government's estimate of 8,500. But the count includes accidents like slips, falls and non-crash events that have nothing to do with seatbelts.

The National Coalition of School Bus Safety (NCSBS), a loose organization of volunteers, says that industry and the NHTSA are shirking their responsibilities to children. "We don't need to reinvent the wheel here, nor do we need scientific studies," says Alan Ross, NCSBS president. "Seatbelts should be federally mandated. We have the available technology to use them for children of all sizes now."

NHTSA, on the other hand, wants to hear all sides before it makes its next move. "We were pleased with the tremendous amount of information and different views discussed at the School Bus Safety summit," said NHTSA Administrator Nicole Nason. "We are currently analyzing the data to develop proposed changes to our current standards for a rule-making this fall."

How Much Is Safety Worth?

Only one state, California, currently requires lap/shoulder safety belts on all new school buses. Texas has legislation pending that will require lap/shoulder belts on all new buses beginning in 2010, if funding is approved in 2009.

But funding is an issue for most school districts. The estimated cost of adding lap/shoulder seatbelts on school buses is an additional $10,000 over the $75,000-$100,000 cost of a new bus. One hundred belt-equipped buses would cost an extra $1 million. Plus, safety belts use up space, and that translates to fewer seats on new buses; estimates vary from 6 percent to 25 percent fewer. That could mean even more money would be necessary to pay for extra buses — often paid by higher property taxes on retirees in rural and suburban areas, where buses are most needed. Or it could mean fewer buses, which would force children to travel in other, less safe ways.

For her part, Agran is undeterred by cost. "The average life of a school bus is 11 years. Over 11 years it amounts to about 10 cents a day, per seat. Any parent would agree to that for their child's safety. People who oppose this initiative won't talk about insurance and liability claims if a kid is injured. If one kid is injured and gets a payout, it can be $100,000."

Other Factors To Consider

Besides the safety benefit, there may be other reasons to encourage seatbelts on school buses. A University of North Carolina pilot study found that parents liked the idea of lap/shoulder belts because they felt it would keep kids in their seats, reducing incidences of bullying on the bus. Ironically, these restraints require raising the seat height from 24 to 28 inches, making it more difficult for drivers to keep an eye on students.

Then there's the problem of making students, particularly teenagers, wear lap/seatbelts if they are, in fact, mandated. Bob Riley, executive director of the National Association of State Directors of Pupil Transportation Services (NSDPTS), which represents manufacturers and private contractors by state, says new standards would be fine, but that "standards will only work if someone on site is making sure that seatbelts are used and used correctly. NHTSA should issue standards and leave the [enforcement] decision up to the states."

Right: No matter what the federal government says, someone at the local level would have to make sure that those teenagers buckle up.