A new grade of fuel called E15, a blend of 15 percent ethanol and 85 percent gasoline, is very slowly wending its way into the marketplace. Proponents say E15 fuel will help Americans by reducing gas prices and fostering energy independence. But there's also a debate raging over whether any savings at the pump would be offset by more frequent (and costly) engine and fuel system repairs.

Most consumers won't have to grapple with the problem any time soon. E15 fuel has been approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for use in passenger cars from the 2001 model year or later, and it is being promoted in several Corn Belt states where ethanol is a major product. But it faces a number of political, regulatory and economic hurdles and its market introduction, which began with a single gas station pump in 2012, has been glacially slow.

It also had faced a lawsuit, brought by the automobile industry's key trade group and a mélange of groups representing the motorcycle, boat, off-road and agricultural equipment industries. They allege that the E15 fuel hasn't been tested sufficiently to guarantee that it won't damage engines in which it is used.

But the case was dismissed by a federal court that ruled that the manufacturers did not have legal standing to file the suit. E15 opponents appealed that decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case and let stand the lower court's decision.

Citing the results of new tests that show "substantial" failures of fuel pumps and other equipment designed for post-2001 model year passenger vehicles, the American Petroleum Institute also has called on Congress to order the EPA to repeal its E15 authorization: a call that has gone largely unheeded.

Why Would Consumers Want E15?

Ethanol is about $1 a gallon cheaper than gasoline at the wholesale level. If the full savings were passed along at retail, diluting gasoline with 15 percent ethanol would make the resulting blend about a nickel per gallon cheaper than the E10 blend of regular unleaded gasoline that now accounts for most of the nation's motor-vehicle fuel.

It would lower the price of the blended fuel by about 15 cents a gallon compared to the so-called "pure gas" that can still be found at pumps in some states, particularly in the South. (Pure gas doesn't contain any alcohol additives. It costs a bit more than the more common E10 blend that now accounts for about 90 percent of the nation's motor vehicle fuel, but can be used without worry on all kinds of new and old gasoline engines — from cars and boats to chainsaws and jet-skis.)

Ethanol might be cheaper, but it delivers fewer miles per gallon than gas. Edmunds.com examined that question in a fuel-efficiency road test of E85, which is a blend of 85 percent ethanol and 15 percent gasoline.

With its 15 percent ethanol content, E15 fuel would not reduce mpg enough to erase the benefit of ethanol's cheaper price, says Bob Dinneen, chief executive of the pro-ethanol Renewable Fuels Association. "It's a win for consumers," he says.

We Do the Math

It might actually be more of a wash than a win. Given the disparity in energy density, E15 would deliver about 5 percent less fuel economy than gasoline, versus a 3.5 percent decline compared to everyday E10 fuel. Efficiency for a specific vehicle would depend on terrain, temperature, vehicle type and load, the way the engine is tuned and the manner in which the vehicle is driven.

On the cost side of the equation, if an E10 blend of fuel were selling at $4 a gallon, an E15 blend would be about $3.95. This would represent a savings of just 1.3 percent. Over 10,000 miles, the driver whose car gets 27 mpg using $4-a-gallon E10 would buy 370 gallons of fuel, at a cost of $1,480. Switching to an E15 blend would increase fuel consumption to about 375.5 gallons, at a cost of $1,483.23.

In such a case, the real winner would be the ethanol industry, which would benefit from a 50 percent increase in demand if E15 became ubiquitous.

The Corrosion Question

One of the chief complaints by E15 opponents is that ethanol (an alcohol) is corrosive to many of the metals, plastics and rubber components used in internal-combustion engines and their fuel systems.

That's the case whether the ethanol is derived from corn, as is most ethanol made in the U.S., or from sugar cane, the preferred feedstock in Brazil. Corrosion also is a problem with what's called "cellulosic ethanol," which is derived from waste material and woody non-food plants such as switch grass, wood pulp or algae. Cellulosic ethanol is just now beginning to be produced for commercial use.

The auto industry and other E15 doubters cite corrosion as one reason more study is needed before the fuel is released. While modern engines have been designed with E10 blends in mind, their ability to use E15 for prolonged periods without damage hasn't been sufficiently tested, opponents argue.

Dueling Studies

In support of E15 fuel, its backers presented the EPA with a study that says there's no statistical evidence that the new blend is any more harmful to vehicles built after 2000 than is E10. Additionally, the federal Department of Energy says it has tested vehicles on E15 for a total of nearly 6 million miles — on test tracks and dynamometers — without finding any engine or fuel system damage.

But opponents countered with a study of their own that says several post-2001 engines run on E15 for a substantial amount of time showed substantial damage due to the fuel's corrosiveness.

Additionally, new test results released in January 2013 on fuel pumps and fuel-level sending gauges designed for 2001 and later models show that a "substantial number" failed at 50,000-60,000 miles of use, according to the petroleum institute's Coordinating Research Council. The council is made up of fuel and automotive industry representatives.

Test results showed that fuel pumps broke down because of corrosion and that fuel-level sending units began malfunctioning, causing inaccurate fuel gauge readings and unnecessary "check engine" warning lights initiated by vehicles' onboard diagnostic systems.

Opponents of E15 fuel also argue that its use without proper controls could endanger the estimated 40 percent of all passenger cars and light trucks on the road today built before the 2001 model year and not approved for E15.

Engines with carburetors — as opposed to the more recent and more sophisticated fuel-injection systems with electronic controls for mixing fuel and air — are particularly susceptible to problems when running on gasoline-ethanol blends.

Unsurprisingly, each side says the other's study is flawed.

Other Issues in E15 Fuel Adoption

There also are concerns that many service stations would either have to abandon one grade of fuel they now sell in order to make room for a new E15 grade, or add additional pumps and underground storage tanks.

While not a deal-breaker for stations just being built, that could be an expensive proposition for existing stations, says Kirk McCauley, a representative of the Service Station Dealers of America, a trade group of independent station owners who mainly are located along the Eastern seaboard. "It wouldn't be economically feasible for many to have to tear up an existing place to put in new pumps and tanks."

In any event, he says his group isn't endorsing E15 at this time, citing "the potential liability if a customer misfuels and his car is damaged."

Labeling Required

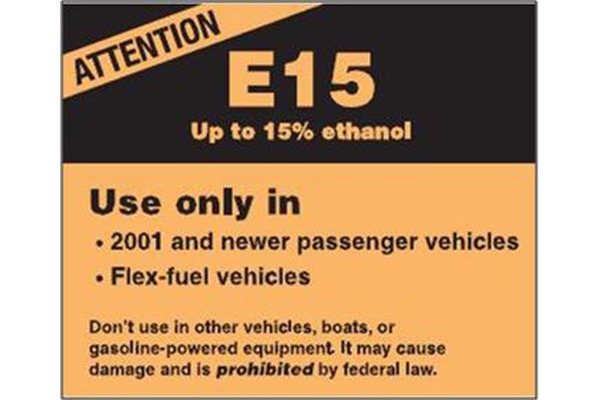

One requirement imposed on the ethanol industry by the EPA is that E15's rollout be accompanied by a "misfueling mitigation" plan to protect consumers from damaging engines not approved for E15 use.

The solution that's been approved is a relatively small (3.6 by 3.5 inches) orange and black label for E15 pumps. In large type, it says: "E15, Up to 15 percent Ethanol; Use only in 2001 and newer passenger vehicles [or] flex-fuel vehicles."

The small print below says: "Don't use in other vehicles, boats, or gasoline-powered equipment. It may cause damage and is prohibited by federal law."

That's sufficient warning and information to keep people from misfueling cars and other equipment, says Dinneen.

Skeptics, though, worry that the E15 label is too vague. With several major automakers saying they won't honor warranties even on their newest models if E15 is used and causes damage, the fuel's opponents say that the label simply adds to the confusion.

Congressional Efforts Sputter

Ethanol backers are trying to ease that concern and in 2012 persuaded a bipartisan group of U.S. representatives to back a bill that would have relieved fuel retailers, oil companies and carmakers from liability related to use of federally approved fuels such as E15.

That bill died in committee and was replaced in 2013 by a new measure, H.R. 1214 that is backed only by a group of a dozen Republican legislators and is still awaiting action.

The measure faces an uphill battle. Congress in the past has shied away from such broad liability relief. Further, a powerful coalition of environmental and consumer groups, engine manufacturers and fiscal conservatives has come together to oppose the measure. It is concerned that government would end up with the liability.

At the same time, 14 automakers selling cars and light trucks in the United States have sent letters to Congress urging delay in approving E15. So far, the only response has been one measure that died in committee.

Automakers Want More Testing

In their letters, automakers including Ford, General Motors and Toyota say E15 fuel hasn't been studied enough. They are members of the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, which represents most major car companies.

At present, BMW, Chrysler, Nissan and Toyota have said that the use of E15 can invalidate their new-car warranties if the fuel causes damage. Toyota has gone so far as to add a warning label on the fuel-filler caps of its models from 2012 onward, stating: "Up to E10 gasoline only."

Toyota has told the EPA that it doesn't believe the agency testing that led to approval of E15 for later models is adequate, says Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A. spokeswoman Cindy Knight. "Vehicles are simply not designed for it."

Ford Motor Co. is a little more accommodating. The automaker is still cautious and supports additional testing of E15's impact on engines and fuel system components, but beginning with the 2013 model year, new vehicles bear a label in the fuel filler area that says blends of up to E15 are acceptable.

Ford supports "the use of biofuels to address climate change and energy security concerns," says Cynthia Williams, fuel policy chief for Ford. But the carmaker does not believe that the potential risks of using E15 have been addressed. Ford doesn't support E15 use in its older vehicles, and owners of the newest Ford models should be guided by the fuel recommendations in their owner manuals, she says.

General Motors Corp. has now approved E15 for its 2012 and newer models and Porsche has approved it for all of its vehicles introduced since the 2001 model year.

"It's rolling slowly, but we're still leaps and bounds ahead of where we were with E10 a year after it was introduced," says Robert White, director of market development for the Renewable Fuels Association. "It took six years for E10 to be included by automakers" as an approved fuel.

First Appearances of E15

Controversy notwithstanding, the EPA has approved applications from almost two dozen fuel blenders that plan to produce E15. The ethanol industry is funding an EPA-required national survey to determine where and how much E15 is expected to be sold.

The nation's first E15 pump was installed in 2012 in Lawrence, Kansas, and as of June 2013 there were 24 E15 outlets in seven corn belt states, with most of them clustered in Kansas, Illinois and Iowa.

The ethanol-boosting Renewable Fuels Association expects more E15 availability as individual states update their fuel-blending specifications to permit increased use of ethanol.

"It's been slow for several reasons," says White. "The anti-E15 people scared a lot of retailers by saying they could be liable for damages to customers' cars."

Some franchise agreements have been written to make it almost impossible for a gas station operator to sell E15, he says. One major oil company requires its franchised stations to sell only the fuels it provides, for instance, and it doesn't provide E15.

E15 is presently not permitted at all in 18 states and is restricted in more than 30 others. Most states with regulations that bar E15 aren't actively opposed to the fuel, though. They just have fuel-specification regulations that were written when E10 was the most ethanol-intense blend available. They would need to update those rules to include E15.

In a recent report to the Society of Automotive Engineers, one industry consultant estimated that all regulatory blocks to E15 could be removed by 2014.

An Option Only

Initially, at least, E15 will appear as an additional choice at the pump, not a replacement for the blend of gasoline and up to 10 percent ethanol that is the passenger vehicle fuel most widely sold in the U.S.

Consumers who don't want to try the higher ethanol blend won't have to.

In some states, California prime among them, tight fuel standards aimed at reducing emissions including pollution from evaporation emissions will prohibit E15 altogether. One of California's top clean-air regulators has said it would take several more years of study and testing before the state's Air Resources Board could decide whether to approve E15 for use.

Why Ethanol Could Proliferate

Despite the objections to E15, ethanol backers believe that political and economic pressure for energy security and cheaper fuels will ultimately win out, making a place for higher blends of ethanol in all 50 states.

There also is the embattled federal Renewable Fuels Standard, which requires increasing use of ethanol in transportation fuels each year. At present, the plan calls for ethanol to account for more than 11 percent of the passenger vehicle fuel sold in the U.S. in 2014. That's a goal the ethanol industry could not reach if fuel producers refuse to blend E15 in quantities.

Although the EPA has recently indicated willingness to reduce some of the requirements for ethanol, at present the only way the fuels industry can meet the Renewable Fuel Standard goals, ethanol supporters say, is to increase the amount of ethanol that's blended into petroleum-based gasoline.

Despite opponents' concerns, consumers shouldn't worry about the fuel, Dinneen says. "E15 is the most studied fuel in history."

It May Be up to You

Ultimately, acceptance or rejection of fuels with higher ethanol content is going to be up to the consumer. If the biofuels industry can overcome concerns about engine damage and can demonstrate that increasing ethanol content meaningfully reduces the retail price of motor-vehicle fuel, E15 might catch on.

If not, then fuel retailers won't see increased demand and won't be motivated to make the often-costly changes needed to bring E15 fuel to their pumps. In that case, it would take government intervention, likely prompted by energy security concerns, to require automakers to design their fuel systems to handle blends such as E15 and even E20, and fuel suppliers to provide the higher alcohol blends.

In the meantime, don't expect the confusion to lessen any as the argument over ethanol's economy, efficacy and efficiency continues between the corn-grower-dominated renewable fuels industry and the nation's engine and automobile manufacturers.