President Obama made headlines a few years ago when he proposed a new generation of federal fuel economy standards that would give us passenger vehicles that by 2025 would be averaging the equivalent of 54.5 miles per gallon. That number has been tossed around by media, politicians and environmentalists all over the country ever since, and "54.5 mpg" has become gospel whenever the media covers the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards for 2017-'25. (For a short history of CAFE and its testing, see our CAFE FAQ.)

Yet the headlines obscure an important fact embedded in the fine print of the new standards: 54.5 mpg merely reflects the best guess of those who jointly concocted it. It is not a mandatory target. It's just a goal that will change with market conditions.

Here's a look at the good, bad and variable aspects of CAFE for vehicle buyers.

1. CAFE Gives Carmakers Lots of Leeway. While pro- and anti-CAFE forces have praised and blasted the 54.5 mpg figure, there is nothing in the reams of CAFE documents prepared by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that says automakers must fashion a passenger vehicle fleet that by 2025 will deliver an average fuel economy of 54.5 mpg. Not only do trucks and cars have separate requirements, the plan is surprisingly flexible, permitting automakers to build and sell whatever models they think consumers will buy. The catch, of course, is that the fuel economy for those cars and trucks will have to ratchet up significantly over the 13-year span of the plan, adding to the production cost and purchase price of most models.

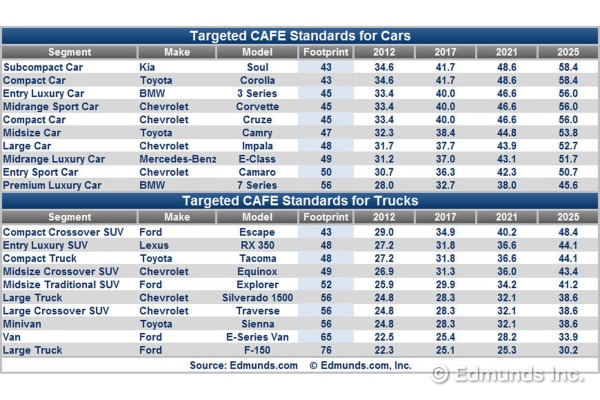

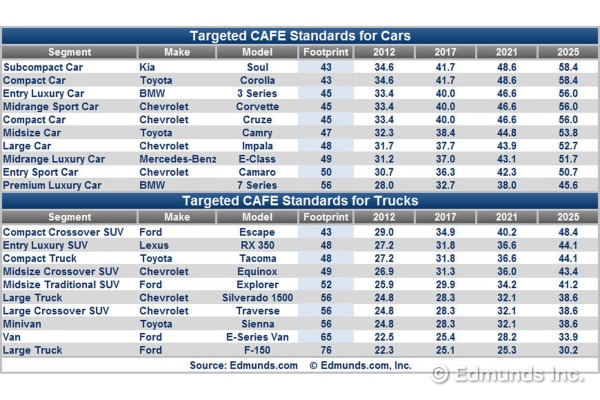

The plan adjusts actual annual mpg requirements to match the industry's real-world production tallies and the end of each year. That's done by assigning fuel economy targets based on a so-called footprint system. Vehicles are measured and categorized by the square footage between the points where their tires touch the ground. Regulators express this as track width multiplied by wheelbase.

The chart below shows the footprints and CAFE targets of several best-selling 2011 model-year cars and trucks, as well as some other 2011 vehicles in key segments. Some of the SUVs shown may have to be redefined as cars in future model years unless they evolve to meet CAFE's footprint definition for trucks: or, as regulators put it, "non-automobiles."

Rather than set an inflexible annual efficiency standard for each automaker and for the industry as a whole, the rules set standards for each automaker that are based on the footprints and production volumes of the different vehicles the automaker produces. While the standards are estimated at the beginning of the model year based on data supplied by the automakers, the actual annual requirements are not fixed until the model year is done and real production and model mix numbers come rolling in.

From there, regulators derive a given manufacturer's actual fleet performance by combining this as-built model mix with the measured mpg values for each vehicle footprint. Annual compliance boils down to the degree to which this number agrees with the locked-in manufacturer target.

There are footprint-based target curves, one each for passenger cars and light trucks for each model year. They escalate each model from 2017 through 2025. The exception is the largest light trucks, for which targets are nearly unchanged in model years 2017-'21. (The 2021-'25 rules are subject to revision after a midterm assessment expected to occur early in 2018.) So air quality should improve and oil use should go down, unless people significantly ratchet up their driving, a phenomenon called the rebound effect.

Nothing in the standards requires automakers to make vehicles they can't sell. There are, however, incentives for building alternative fuel vehicles (such as electric cars and hybrid pickups) that to date haven't had much in the way of broad consumer acceptance. The incentive to do so is that building these highly efficient vehicles will give automakers credits they can apply to offset the inefficiencies of some of the larger cars and trucks they will be building.

2. MPG Confusion Will Continue. CAFE's goal is to achieve a 2025 fleet average fuel economy of 49.6 mpg (as expressed by NHTSA). But the test system enshrined by Congress in 1976 cannot adequately capture the benefits of certain fuel-saving and CO2-reducing technologies. To paper this over, regulators established a system of credits, and the use of such credits is what boosts the EPA's CAFE number to the equivalent of 54.5 mpg: the figure usually cited by the administration, members of Congress and the media. This higher figure is what is required to meet the EPA's requirement that tailpipe emissions of CO2 drop 35 percent to 163 grams per mile by 2025.

The congressionally mandated CAFE tests do more than mask the benefits of certain modern technologies. They're also wildly optimistic. The EPA, NHTSA and everyone in the industry knows this, so a more modern system of tests has been put in place to figure fuel economy ratings for new-vehicle window stickers. That program is not subject to CAFE's congressional mandate. The 54.5-mpg figure equals about 36 mpg in the EPA's current window-sticker measuring system. So despite what the politicians and headlines say, forget the idea that all cars and trucks will be delivering somewhere around 54.5 mpg 13 years from now. That simply won't happen.

We could get mpg clarity someday, however. NHTSA received a number of complaints about the disconnect between real-world and CAFE fuel economy figures when it set the rules for the 2012-'16 period. It would literally take an act of Congress to change the methodology for computing official CAFE numbers, because Congress ordered up the system in the first place.

Sources say that NHTSA isn't averse to pushing for such a change. It could even explore administrative means of implementing a change if the public continues to ask for a more simplified system based on the window sticker fuel economy numbers that are most familiar to consumers.

3. Complexity Rules the New Rules. Why does it take 600 pages to set out the rules for the new CAFE plan? Why are two federal agencies needed to draft the plan? It would make so much more sense if EPA and NHTSA would simply tell carmakers: "We don't care how you do it, but make cars and trucks more efficient each year until by 2025 the whole fleet is achieving an average of 36 mpg."

That sounds nice, but the regulators tell Edmunds that with two dozen auto companies and hundreds of individual models with scores of different powertrains and several types of fuel in play, simplicity can't be applied in a fair and equitable manner. A single annual fuel economy number applied to all makes and models would be patently unfair, NHTSA argues. It would force manufacturers of large vehicles to quickly make huge improvements at great cost while makers of smaller, more efficient vehicles would face a much easier job.

Even more complexity comes from the way the CAFE mandate has changed over the decades. Congress put CAFE in place in the 1970s to help reduce oil consumption via improved passenger-vehicle fuel economy. But then Congress subsequently reacted to court decisions that involved the EPA's authority to regulate greenhouse gases and recently inserted the environmental agency into the CAFE process. So now CAFE has become policy for greenhouse gas reduction rather than a policy strictly for fuel economy. The machinations necessary to harmonize the different goals of Congress and the EPA have, unsurprisingly, increased the complexity of the program.

4. It's Harder for Automakers To Game the CAFE System. Because CAFE requirements are now based on vehicle footprints, with lower required annual mpg increases for vehicles with bigger footprints, it would seem easy for automakers to reduce their fuel-economy burdens by enlarging the footprints of some models. That's a fairly inexpensive strategy if the vehicle modification simply means increasing the width of the track between the tires, but such a measure only would deliver a very small increase in footprint. A significant increase in footprint can only come by stretching a vehicle's wheelbase, which is not only a complex manufacturing proposition but also an expensive one.

NHTSA said that it recognized the apparent loophole early on and took steps to plug it. It ensured that the incremental reductions in fuel economy requirements would be so small that it would not be economical for an automaker to merely step up one or two footprint sizes. The cost of stretching footprints beyond that, the agency said, would be far greater than the benefit an automaker would receive from the mpg reduction.

In short, the shape of the footprint curves has been carefully tailored to allow the continued existence of larger vehicles without favoring them over smaller ones.

The new plan also redefines trucks and cars in such a way that the carmakers can no longer play the old game of turning a car into a truck by simply flattening the load floor. (That's what Chrysler did with the discontinued PT Cruiser.) Unless they have four-wheel- or all-wheel-drive systems, most of the small crossover SUVs, such as the Ford Escape, are classified as cars. This means these crossovers must meet tougher fuel economy standards and can no longer be quietly slipped into an automaker's truck fleet under a technicality in order to reduce the average fuel consumption of the truck fleet.

But where there is a will there's a way. It's likely that some enterprising automaker will figure out a method or two for improving its fleet fuel-efficiency average in a way the rulemakers never envisioned.

5. There Will Be More Math for Car Shoppers. NHTSA and the EPA estimate that if all goes as projected today, the various new technologies that will be employed so cars and trucks can hit their CAFE goals will add an average of $1,946 to the cost of a new vehicle in 2025. That's assuming there are no significant changes in global oil and gasoline prices, no disasters that wipe out a nation's automobile production capacity and no automakers that go broke and shut down.

But this estimate of an average increase in price doesn't tell the full story. While the increase might hover in the range of $2,000-$2,200 for a big, full-line car company such as Chrysler, Ford or General Motors, the projected price increase goes as low as $1,483 for Toyota and as high as $7,109 for Ferrari. And within the lineup of individual automakers, the estimates of added costs will also vary. In Toyota's case, for example, there's likely to be almost no additional cost for a Toyota Prius, but a Toyota Tundra might pick up $2,000 or more in additional costs.

The lesson here is that shoppers really need to look at these projections in incremental cost and compute the estimated fuel savings per year to see if a car or truck will earn back its extra cost with fuel-efficiency savings. Every consumer's purchase decision should include an estimate of a vehicle's lifetime operating costs.

6. CAFE Rules Favor Certain Technologies. NHTSA says this isn't the case, but NHTSA only writes half the rules this time. The EPA, in its quest to lower greenhouse gas emissions, has established special credits for hybridizing large pickups and for all-electric, plug-in hybrid and fuel-cell electric powertrains.

Additionally, Congress over the years has mandated special treatment for bi-fuel and flex-fuel vehicles, the most notorious example being the credit for vehicles fueled by ethanol. The ethanol credit is slated to fade away soon, but in the past it has allowed carmakers to overestimate the CAFE impact of the flex-fuel gasoline-ethanol vehicles they sell, since there was no one to ensure that a vehicle owner would use ethanol rather than conventional gasoline. (For example, GM sells thousands of flex-fuel SUVs and pickups in California, but there are fewer than 50 public ethanol stations in the state, and only four in the entire greater Los Angeles area.)

7. Full-Size Pickup Trucks Will Survive. The yearly fuel-efficiency increases demanded of trucks are more modest than those for cars. What's more, NHTSA's curve for projected efficiency increases by truck footprints becomes less aggressive at the end of the scale where full-size trucks reside. Regulators did this intentionally, recognizing that full-size pickups that are meant primarily to perform such jobs as towing or hauling substantial loads will have the hardest time meeting ever-increasing standards of fuel efficiency. The physics just doesn't add up.

The regulations also seem to acknowledge that pickup trucks will continue to play an important role in the market. Because full-size pickups come in many different wheelbase and cab configurations, the footprints vary widely within a given model and, as such, the target fuel economy increases are easiest for the long-wheelbase versions. These are the vehicles that are generally purchased by people who really need to tow and haul.

Furthermore, full-size trucks are eligible for special credits for hybridization (at least 10 percent of a manufacturer's truck production would have to be hybridized). They also get credits for exceeding their footprint-based mpg targets by certain margins. Passenger cars and midsize and compact trucks don't qualify for those credits.

The way trucks are treated may be the most political aspect of the entire 2017-'25 CAFE program, since it's clearly U.S.-label brands that stand to gain the most from the continued popularity of trucks. On the other hand, any automaker can enter this segment if it chooses to do so. If automakers decide that the lower fuel efficiency targets for large trucks are easier (and cheaper) to hit than the car targets, there could actually be a net increase in the number of full-size pickups, especially in years when the price of gas isn't high.

8. Fuzzy Outlook for Smaller Pickups. If there were hope that increased fuel economy standards would lead to more compact pickup truck choices (and the return of enthusiast-oriented vehicles like the El Camino), it may have been dashed. Such vehicles have smaller footprints, which carry with them the burden of larger annual fuel-economy improvements. This may help explain why Ford said in 2011 that the redesigned Ranger compact pickup, launched elsewhere around the globe, wouldn't be sold in the U.S. GM, however, said early in 2013 that it would introduce two new midsize pickups for the 2015 model year. It seems the jury's still out on this issue.

9. Big Changes Possible for SUVs. Full-size SUVs do not meet the definition of full-size pickup trucks, so they are not eligible for the extra hybrid credits. Automakers with hybrid SUVs would benefit from the direct fuel-economy benefits such systems provide, however. For example, the Chevrolet Suburban has a footprint of around 61 square feet, while the shorter Chevrolet Tahoe sits at 55 square feet. This means the Tahoe faces a stiffer challenge in meeting future fuel-efficiency targets. It would seem that GM is faced with a choice between adding fuel-efficiency technologies to the Tahoe that would run up its price (and drive down sales), or reduce or eliminate Tahoe production in order to save the cost of CAFE compliance.

One choice for automakers is to shift full-size SUVs to unibody construction. SUVs in the small and midsize market segments have been heading in this direction for some time now, and full-size SUVs could be next to lose their body-on-frame construction. Unibody construction would reduce the weight of full-size SUVs for increased fuel efficiency, although it could also reduce towing capacity, which could increase demand for big pickups.

Midsize and larger crossovers and minivans will continue to exist. Like everything else, they'll need to steadily improve, but they are well positioned to do so. Smaller crossover SUVs like the Honda CR-V and Toyota RAV4 may change slightly, because SUVs with gross vehicle weights under 6,000 pounds are defined under CAFE as trucks only if they have four-wheel or all-wheel drive. The two-wheel-drive versions of these "cute utes" are considered cars and will have to meet the tougher passenger car standards.

Clearly, there are winners and losers in the new CAFE standards. The next chance for consumers to communicate their thoughts about the plan directly to NHTSA and the EPA will be during the formal review period when the final version of the 2021-'25 portion of the plan is hammered into shape. There's no date yet for that review except a broad statement that it should be completed by April 2018. We'll keep you posted.