The Obama administration has issued an historic set of far-reaching federal fuel economy rules that aim to nearly double the present passenger fleet average by 2025. The Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, approved on August 28, 2012, set a 54.5-mpg average fuel-efficiency goal for the 2025 model year, up from 27.6 mpg in 2011. The rules are expected to shape the cars that automakers will build over the next several years, changing their features and some of their basic functions — as well as raising their price tags.

Here are some frequently asked questions about CAFE, along with our answers.

Question: What is CAFE?

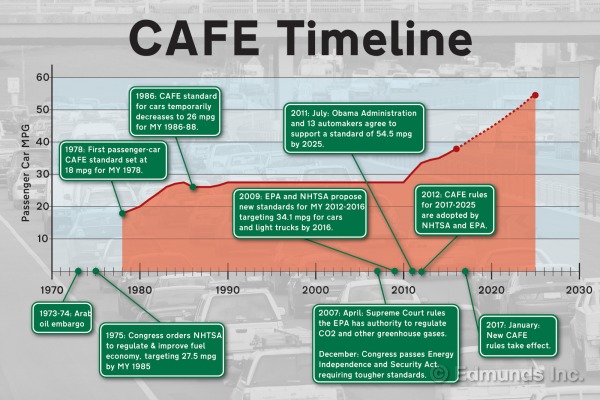

Answer: CAFE is an acronym for Corporate Average Fuel Economy, a fuel economy standard program originally developed in the wake of the 1973-'74 Arab oil embargo.

Q: Why was it created?

A: To reduce oil consumption. Stung by the embargo and its effect on the U.S. economy, Congress in 1975 passed the Energy Policy Conservation Act (EPCA), seeking to reduce oil consumption by increasing the fuel economy of cars and light trucks. "Energy independence and security" and "environmental and foreign policy implications" were important considerations, according to a program history in federal documents. Congress charged NHTSA with administering the program, which required each automaker to hit certain fuel economy targets for its fleet, meaning the vehicles sold in a given model year.

Q: How is mpg measured for CAFE?

A: Cars come into a temperature-controlled lab and are strapped to a dynamometer, a large in-ground roller that simulates road forces. The "dyno" allows a car to be put in gear and driven at speed without going anywhere. Trained drivers operate the throttle and transmission to precisely follow two standardized test patterns that scroll across a monitor screen, videogame style. One pattern represents city driving and the other mimics highway driving. (More about CAFE testing later.)

Q: What changes in fuel-efficiency has the law required so far?

A: CAFE has pushed up average fuel economy at a fairly gradual pace. At its inception in 1978, the program's near-term goal was to double new-car fuel economy, raising it to 27.5 mpg by the 1985 model year. Except for the period from 1986-'88, when NHTSA lowered it to 26 mpg, the CAFE standard of 27.5 stood for several years.

In April 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the statutory authority to regulate emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases from new motor vehicles — something the agency had declined to regulate previously.

In December 2007, Congress enacted the Energy Independence and Securities Act (EISA), amending the EPCA of 1975 and requiring "substantial, continuing increases in fuel economy standards." As far back as 2002, California had wrangled with the federal government over the state's congressionally granted authority to set its own emissions standards.

All these events set the stage for a joint proposal in 2009 by the EPA and NHTSA to establish new vehicle standards for 2012-'16 model years. These were finalized in April 2010 and required that carmakers achieve a standard of 34.1 mpg for cars and light trucks by 2016. California agreed to adopt that standard.

Then in July 2011, President Obama and 13 automakers announced an agreement "to pursue the next phase in the Administration's national vehicle program," increasing fuel economy to 54.5 miles per gallon for cars and light-duty trucks by 2025. (More about that 54.5 mpg figure later.)

Q: How does this new CAFE standard differ from others?

A: It covers a longer period and significantly ratchets up the fuel economy gains and emissions reductions of cars sold in the U.S. The plan is really a continuation of the one established for the 2012-'16 period, which will end with a NHTSA CAFE standard of 34.1 mpg. The new plan covers a nine-year period, which is twice as long as previous ones. It accelerates the rate of increased fuel-efficiency to be required of automakers, averaging close to a 4.3 percent year-over-year improvement across the plan's lifespan. By category, the plan calls for annual improvements of 5 percent for passenger cars and 3.5 percent per year for light-duty trucks in the initial 2017-2021 model years. The annual improvement figures for light duty trucks for the 2022-'25 period are still being developed but will average 5 percent per year.

The stated goal of the new plan, which is subject to reevaluation in the middle of the nine-year period, is to achieve a fleet average fuel economy of 49.6 mpg through real improvements. This would be kicked up to the equivalent of 54.5 mpg — the figure that the administration, EPA, NHTSA and most news media most often cite in public announcements and articles — by use of various offsetting credits in order to meet the EPA's requirement that overall tailpipe emissions of CO2 drop to 163 grams per mile. The 163 grams-per-mile figure would be almost 35 percent lower than the 2016 CO2 level.

Q: Why does the plan cover such a long period?

A: In theory, pushing the national fuel-efficiency and greenhouse-gas reduction goals out to 2025 makes it easier for automakers and regulators to do their planning. In actuality, federal law prohibits NHTSA from setting CAFE rules for more than five years at a time, so the "2017-'25" plan is actually divided into two parts. The final plan establishes firm standards for the 2017-'21 period, but the portion dealing with fuel-efficiency for the 2022-'25 period is presented as a proposal.

There will be a review around 2020 so that automakers and regulators can negotiate the specifics of the final four years of the plan, taking into account the state of the industry and the various technologies at that time.

Q: Why are the CAFE mpg numbers so much higher than what's displayed on the carmaker's window sticker seen on a new car?

A: The short answer is that the window-sticker mpg and CAFE mpg are derived from separate tests.

Here's the full story: When CAFE was first put in place, CAFE mpg and window-sticker mpg were identical. The city-cycle lab test determined City mpg and the highway-cycle lab test determined Highway mpg. But almost from the start, consumers began complaining that their cars weren't matching the advertised mpg.

The window-sticker mpg was first "downrated" in 1985, with City mpg pegged 10 percent below the city-cycle test result and Highway mpg set 22 percent below the highway-cycle test result. When the 55-mph national speed limit was later abolished and states started raising speed limits, consumers then began complaining anew as the mpg they experienced fell even further below window-sticker predictions.

EPA introduced a second window-sticker downgrade in 2008, and this time it came with three new mpg tests. These accounted for higher speeds, cold weather and hot weather, plus the use of air-conditioning in the test for the first time. Today, there are five tests all contributing to the mpg you see displayed on a new car's official window sticker of pricing and fuel-efficiency.

CAFE results and accounting practices never changed to match the ratcheted-down window-sticker mpg figures, however. CAFE mpg still comes from the original pair of tests that are now widely viewed as bad predictors of real-world mpg. The 34.1 mpg CAFE target for 2016 is actually equal to only 26 mpg on a window sticker. The talked-about 2025 CAFE standard — usually described as 54.5 mpg — amounts to a figure of 36 mpg Combined on a window sticker.

Q: Why haven't the CAFE procedures been changed to match window stickers?

A: Politics and momentum. Everyone in the industry and the regulatory community knows the history of CAFE testing — and its pros and cons — by heart. Realigning CAFE mpg to match window-sticker mpg would make the current and 2017-'25 CAFE numbers plummet, and in the view of some, this would make it seem as though the nation was losing ground rather than progressing toward better fuel economy and fewer emissions. Politically, it would be very difficult to switch testing protocols, even though it would render a more accurate result.

Yet the huge disparity between CAFE numbers and the window-sticker fuel economy numbers actually works as a political opportunity for both supporters and critics. For those in favor of CAFE, the higher numbers make it look like a lot is being accomplished. Opponents can use the high numbers to argue against "Draconian" regulations requiring such massive increases.

Even when industry professionals and other interested parties are using the old testing method to arrive at CAFE mpg, they still can have intelligent discussions about percentage improvements that the fleet achieves year after year. The big problem is that the existence of two sets of mpg figures makes it very hard to explain to the public what's really going on.

Q: What are the biggest changes in the 2017-'25 plan?

A: Credits for the use of new technologies. Automakers will get significant credits for introducing newer fuel-saving and emissions-reducing technologies.

They'll be credited for battery-electric vehicles, compressed natural gas vehicles and for using hybrid powertrains such as gas-electric and diesel-electric, plus forthcoming new hybrid technology for large pickup trucks that features compressed natural gas and electric. Automakers also will get credits for widespread use in their fleets of what's called "off-cycle" fuel-saving technologies. These are technologies that can improve fuel-efficiency but aren't directly related to the engine and its air emissions. The proposed version of the rules required that that they use those technologies in at least 10 percent for their vehicles to gain credits. That was dropped in the final version.

Q: What technologies would be eligible for credits?

A: The list is lengthy. Technologies include such things as the use of non-hydrocarbon air-conditioner refrigerants and electrically powered air-conditioning systems; active grille shutters to modify airflow and improve aerodynamics; high-efficiency lights and alternators; vehicle stop-start systems; electric heat pumps that place fewer demands on an engine when they operate; solar panels on electric vehicles and hybrids that produce at least 100 watts of power to help with battery charging; and engine-heat recovery systems that convert heat to electricity. Other technologies are being discussed and they'll receive a specific carbon-credit value that can be applied against the EPA's CO2-based target.

In fact, we're starting to see some of these technologies now. That's because the EPA standard allows certain surplus credits to be carried forward to future years — a little like cellphone rollover minutes.

Q: There seem to be two different mileage figures associated with the 2025 CAFE goal: 54.5 and 49.6. Why is that?

A: The 54.5 mpg figure is actually the EPA's figure. It is not, strictly speaking, the CAFE number. The 54.5 mpg figure comes from the EPA's new CO2-based standard, and represents the fuel economy needed to achieve a CO2 target of 163 grams per mile by 2025.

The EPA's CO2 target is not the same as the CAFE mpg target. The discrepancy comes from the fact that EPA and NHTSA operate under different regulatory authority. The EPA's authority under the Clean Air Act permits manufacturers to apply credits for the "off-cycle" technologies that do not affect lab test results. CAFE mpg, meanwhile, is regulated by NHTSA, but the mandate under which NHTSA operates does not allow it to apply such credits. It must strictly go by test results obtained on dynamometer.

In order to "harmonize" EPA CO2 regulations with NHTSA's CAFE targets, NHTSA has set its 2025 CAFE number at 49.6 mpg. That's the equivalent to the EPA CO2-based standard before the EPA-allowed "off-cycle" credits are added in. But if you're trying to apply those to real-world window-sticker mpg, think in the vicinity of 36 mpg.

Q: Whether it's 49.6 mpg or 54.5, will automakers be able to comply with the new standards?

A: Most companies say that they will. Thirteen major automakers signed the preliminary agreement worked out with the White House. (There also were some non-signers.) Regulators, environmentalists and most automakers agree that existing technologies can be used to achieve this plan's goals — although there is a lot of debate about their cost.

And while some critics believe that compliance will dramatically alter the automotive landscape, eliminating some types of vehicles altogether, most automakers say they don't see that happening.

Compliance will require dramatic changes in the types of powertrains offered, however. The cost of the average vehicle will rise, thanks to such expensive technologies as turbocharging, direct fuel injection, 8- to 10-speed automatic transmissions, electric drive and other fuel-saving and emissions-cutting measures. These technologies now are limited to a few, usually high-end vehicles, but to achieve the goals set, they will need to be spread widely throughout the vehicle fleet.

Q: Just how much will the new standard affect the retail prices of cars and trucks?

A: The jury's really out on this one. Although there is general agreement that achieving the goals will add to the cost of new vehicles, estimates range from a low of just under $1,000 a car to a high of $9,300. EPA and NHTSA estimate that the range of costs for achieving a 4- to 5-percent annual improvement in fuel-efficiency and greenhouse-gas emissions is about $2,000 per vehicle and say that fuel and maintenance savings would enable consumers to earn that back in fewer than four years. The agencies predict $4,000 in savings over a 2025 model-year vehicle's anticipated 10-year lifetime.

Most of the automakers who have discussed this with Edmunds have said they expect the costs to be applied unevenly. That is, the largest cars, SUVs, vans and trucks are likely to see the biggest price hikes. They will absorb some of the costs of improving the fuel-efficiency and emissions performance of smaller cars, so as not to price those cars out of the market.

Q: How will the standard affect the automotive choices for consumers?

A: People probably will still be able to buy all the same kinds of vehicles in 2025 that they can today. There will be fewer numbers of the largest vehicles, however, and a larger variety of compact and smaller cars and of hybrids — including hybrid vans and trucks. There will be more all-electric cars as well.

Because a key element of the CAFE program is reducing the use of petroleum and other carbon-based fuels, consumers also can expect to see more alternative and flex-fuel vehicles and more non-petroleum fuels.

These would likely include biodiesel, natural gas, battery-stored electricity and ethanols, including those from non-food feedstocks such as woody waste and possibly algae. There might also be some hydrogen fuel-cell electric cars and trucks on the market by the time the second phase of the plan comes up for debate.

Gasoline, however, is still expected to be the most prevalent passenger-vehicle fuel in use in 2025. Cars and trucks with internal-combustion engines that involve some degree of hybridization are likely to be the most prevalent type of vehicle.

Whether consumers will eagerly buy the cars reconfigured by the new standards is an open question.

Q: Will full-size trucks still be available, or will everything become a compact pickup?

A: Full-size trucks will continue to exist — for two reasons. First, the CAFE standard is broken down into separate targets for passenger cars and light trucks. In acknowledgement of their place in the market and their passenger- and cargo-carrying capacity, the light-truck standard isn't as demanding as the one for cars.

But the truck standard is still a challenge for the makers of traditional pickup trucks. They won't necessarily have to meet the standard by simply getting smaller and less capable. That's because CAFE includes a size factor, called the "footprint."

A car or truck's footprint is a measure of the shadow it casts on the ground. But instead of overall length times overall width, the agencies make the measurement where the tires touch the ground, using wheelbase length times track width.

The standard gets somewhat easier as footprint increases, meaning that full-size pickups aren't in immediate danger of extinction. This may pose a problem for compact trucks, though. Their fuel-efficiency target is relatively high for their carrying capacity. Even though it may seem logical to simply downsize, the makers of trucks may decide, ironically, that compact pickups don't pencil out.

Q: Is it true, as some critics say, that by encouraging vehicle weight reduction to help achieve tougher fuel-efficiency standards, the CAFE plan will lead to increased traffic fatalities?

A: Short Answer — not likely. Wholesale bloodletting on the nation's highways is an image that some CAFE opponents might like to imprint on people's minds (perhaps particularly in an election year). But a measureable hike in crash-related traffic deaths isn't likely to result from the changes the fuel-efficiency plan promotes.

Safety is mostly a matter of engineering, and the computer-optimized design techniques and lightweight materials available to engineers have advanced far beyond the industry standards of just a decade ago. The industry is moving toward the use of lightweight alloys and carbon composites that are much stronger on a pound-for-pound basis than their traditional steel and iron counterparts.

The issue is one of cost more than safety. Such materials do cost more to use, and to date, manufacturers have chosen to use the cheaper, heavier materials available to them.

Until they repeal the laws of physics, it is true that a smaller vehicle is at a disadvantage in a crash with a larger vehicle, provided that the larger vehicle is also heavier. But despite some critics' claims, there is nothing in the CAFE plan that requires or even encourages manufacturers to decrease the size of their vehicles.

In fact, a key feature of the new system specifically addresses this issue. The footprint concept eliminates the need for carmakers to raise their CAFE average by building increasingly smaller cars that can offset the bigger vehicles they sell. Instead, the plan encourages increased efficiency at every footprint size a carmaker builds. That means we'll see weight losses and the increased use of advanced materials and design techniques across the board.

In any event, metal-on-metal crashes on the highway aren't the chief cause of fatalities in vehicular accidents. Single-vehicle crashes, in which weight doesn't play such a key role, are the more prevalent type of fatal accident. In 2010, they claimed 11,576 lives, versus 10,687 fatalities from multi-vehicle collisions, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

Q: Do all automakers have to meet the same target?

A: No. The government sees this as an industry-wide standard, meaning that regulators are concerned about the entire fleet of vehicles.

Carmakers whose fleets are already known for their thrift in fuel consumption must continuously improve in CAFE terms, reaching higher goals than those automakers whose vehicles currently do not have a stellar mpg reputation. (No points awarded for prior good fuel economy performance, in other words.) Here's what NHTSA has said about this in its own documents.

"The law permits CAFE standards exceeding the projected capability of any particular manufacturer as long as the standard is economically practicable for the industry as a whole. Thus, while a particular CAFE standard may pose difficulties for one manufacturer, it may also present opportunities for another.

"The CAFE program is not necessarily intended to maintain the competitive positioning of each particular company. Rather, it is intended to enhance fuel economy of the vehicle fleet on American roads, while protecting motor vehicle safety and being mindful of the risk of harm to the overall United States economy."

Q: Can carmakers "game" the CAFE system?

A: Where there's a will there will be a way, but the new rules make it a lot more difficult. There's no question that CAFE is extremely complex. It has a wide variety of credits, and its regulations divide vehicles into multiple categories, each with a different annual goal. In the past that's made it possible for a manufacturer to upsize or downsize a particular vehicle in order to move it into a "better" category, although there have been relatively few cases of that happening.

Now, under the new program, the categories are based on the vehicle's footprint. It's an expensive engineering undertaking to make a significant change in footprint, and NHTSA made sure that the incremental reductions in fuel-economy requirements would be so small that it would not be economical for an automaker to merely step up one or two footprint sizes.

The cost of stretching footprints beyond that would be far greater than the benefit an automaker would receive from the resulting reduction in a miles-per-gallon goal, the agency says.

NHTSA also changed the way cars and trucks are defined, so it is no longer possible to turn a car into a truck and get a lower CAFE goal for it by simply flattening the load floor. That's what Chrysler did with the PT Cruiser several years ago.