The idea that we'll all be driving 35-mpg cars and trucks in a dozen years is all the rage these days after Congress passed and President Bush signed into law a new measure boosting required average fuel economy by almost 40 percent.

But there's still a long way to go, and the new law ratcheting the so-called corporate average fuel economy, or CAFE, standard to 35 mpg doesn't mean the window stickers on new cars sold in the 2020 model year and beyond are really going to show that kind of fuel efficiency.

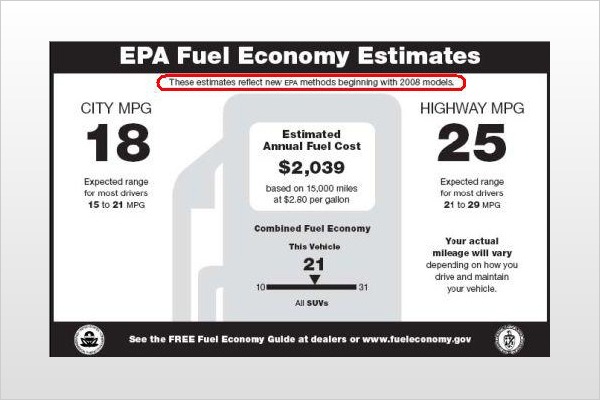

Indeed, CAFE mileage is computed under a different system than the EPA mileage that's posted on all new cars. An analysis by Edmunds.com's Director of Vehicle Testing Dan Edmunds, shows that it takes an EPA rating of only about 26 mpg to achieve a CAFE rating of 35 mpg the way things are done today.

All that, of course, could change — and probably will — as new implementation rules are drafted over the next 18 months or so.

One thing that's almost certain, though, is that to meet the new fuel-efficiency standard, automakers are going to have to tinker with engines, transmissions, tire standards, accessories such as air-conditioning and power steering systems, even the kinds of materials used for frames and body panels.

Expect to see more plastics and lightweight metal alloys, more six-speed transmissions and engines with turbochargers and cylinder-deactivation systems and more use of electronic brake and steering systems to eliminate the weight and parasitic drag of hydraulic components, said Sandy Stojkovski, director of vehicle engineering and total vehicle fuel economy programs at automotive components supplier Ricardo Inc.

She also expects to see a big boost in the use of diesel engines, which can bring a 25-30 percent fuel economy increase over similarly sized gas engines, and "a significant increase in hybrids, which will probably account for more than half the cars sold here after 2020."

The Law The new CAFE rules are part of a larger federal energy bill, H.R. 6, which was signed into law on December 19, 2007.

The section relating to CAFE requires the average fuel economy of the nation's new car and light truck fleet to begin increasing from present levels with the 2011 model year and to reach 35 mpg by the 2020 model year.

How to get there is left up to the individual automakers.

How to tell whether they've made it — the rules, tools and methods for measuring and averaging mileage — is the job of the National Highway Traffic Safety Agency (NHTSA).

Big changes in the rules under the new law start with the hike in average mileage, which will climb from present levels of 27.5 mpg for cars and 22.7 mpg for light trucks: vans, SUVs and pickups.

But there are other significant differences between old and new CAFE.

Selling Credits OK Now One is that the new law permits auto companies whose fleets exceed the mileage standards in any given year to accumulate credits they can sell to competitors who weren't able to achieve the year's average.

Manufacturers get credits now, but can only use them for their own fleets and cannot sell them to others. Companies whose overall fuel economy isn't up to the standard are fined, but the fines are adjusted in subsequent years if any CAFE credits are applied to a substandard year.

The former DaimlerChrysler was hit with a record $30.3 million CAFE violation fine for 2007, largely because the average mileage for its Mercedes-Benz cars fell below the 27.5-mpg mark.

The new law also directs NHTSA to formulate fuel economy rules for medium- and heavy-duty trucks of 8,500-60,000 pounds, and for large SUVs of 8,500-10,000 pounds. All had been excluded from CAFE requirements under the previous measure.

Finally, the new law gradually eliminates a controversial credit for flex-fuel vehicles, which has enabled automakers to get extra mileage credit for cars and trucks capable of running on either gasoline or a gas-ethanol blend even when sold in states, such as California, where ethanol is not readily available.

The flex-fuel credit now can add up to 1.2 mpg to a carmaker's fleet average. The new law has the annual credit declining by two-tenths of a mile per year beginning with the 2014 model year, until it disappears for model-year 2020.

Backed by Industry After steadfast opposition to mandated fuel economy standards, including CAFE — which were nonetheless grudgingly adhered to most years — the auto industry this time around decided to throw in the towel and endorsed the new standard.

"This tough national fuel economy bill will be good for both consumers and energy security," said Dave McCurdy, president of the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, the trade group that represents General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, Toyota, Daimler and five other automakers, in a December interview.

Automakers still will have a lot to say — and likely to gripe about — as the implementing rules are developed. But most believe they can meet the goal by applying a lot of existing technologies that have been considered too expensive in the past but will become more affordable as they are applied to greater numbers of vehicles — and as the price of gasoline and diesel fuel continues to rise.

NHTSA, which has until late this summer (2008) to come up with the rules, isn't talking about things yet. "It's premature to discuss," said an agency spokesman when asked about how the new CAFE law might differ from its predecessor.

So far, NHTSA has asked all automakers that sell cars and trucks in the U.S. for their 10-year product plans so it can determine what kinds of vehicles will be built and sold as the new fuel-efficiency standards are applied.

That's important because, as is the case now, the new system is likely to be built on a sales-weighted averaging scheme.

Also significant, the new law tells NHTSA to use vehicle attributes such as weight, cargo volume, engine size and emissions to devise fuel economy rules, meaning that the average for individual companies can vary depending on the kinds of vehicles they sell.

Presently, the determining factor is first whether the vehicle is classified as a car or truck, and then the vehicle's size — not weight — determined by multiplying the length of the wheelbase by the width of the track, the distance between the centerline of the tires. Cars have a higher CAFE average than trucks, and the larger vehicles in each of those two classes are assigned lower mileage mandates than are the smaller vehicles.

If the same system is kept for the new CAFE, an automaker with a heavy bias toward big trucks and SUVs — Chrysler, for instance — would have a lower annual average to meet than would American Suzuki, whose fleet is made up mainly of small cars and compact SUVs.

Therese Langer, transportation program director for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, sums up how manufacturers and environmentalists alike feel about the new law: "We're not as happy with all this as we could be, but we are happy. It's still a big improvement in fuel economy."