Archived Comparison

Archived Comparison

Pony-car fans have more to be excited about today than they’ve had in 40 years—not only are both the Mustang GT and Camaro SS above the 400-hp threshold, but there’s even a horsepower war raging between the V-6 editions. Next week, we’ll post comparison tests between both the current eights and the sixes, but for now, enjoy this series of past encounters between two of Detroit’s most storied cars.

The Camaro and Mustang first met on these pages in March of 1968, but the clash was part of a six-car showdown—and they finished fifth and sixth, respectively. We knew the two cars had more potential than the relatively wimpy cars Detroit had given us for that test, so for the July issue that same year we invited both to send us the hottest they had to offer. We had the cars delivered to Lime Rock Park in Connecticut, where we met up with Trans-Am wizard-driver Sam Posey.

______________________________________

Originally published in Car and Driver magazine in July 1968.

The Lime Rock pit straight is a wavy, gray blur. Up front two roaring Holleys are trying to suck a hole in the atmosphere. "A 7000 rpm redline? Christ Almighty, it's gonna burst." But it doesn't, and Sam Posey snaps the shift lever into fourth at seven grand as the speedometer climbs past 110 in one of the absolute wildest street machines ever to come out of Detroit. No question about it: we're in the middle of one of the most beautiful goddam road tests in the annals of mankind.

Trans-Am sedans set up for the road. All right, the six sporty cars we tested (March) were exciting examples of the car builders’ art—but they weren't mind blowers. They performed well, almost automatically, never making demands on the driver. But that was their shortcoming. A kind of polished lack of character.

An unsatisfied craving for total driver involvement prompted us to continue our search for that mystical machine. Not a near total fantasy of the Lamborghini Miura or Ferrari 275/GTB-4 sort, but something totally without pretense that might even outperform them. That's asking a lot. Ideally, it should be American. Should we—in the largest automobile producing country in the world—necessarily turn our lust-filled eyes to Europe?

What would it be then? There is always the Corvette, a truly sophisticated GT car, but the Corvette tends to be a glittering boulevard machine with little significant professional competition heritage. The more we thought about it the more we concluded the pure American GT concept is typified by the sporty cars and they are racers. Ask anyone who's seen Trans-Am sedans at 170 mph on the banks of Daytona. Now the plot: according to FIA those scrappy Trans-Am machines are Group 2 sedans and that means the manufacturer has to provide at least 1000 copies. We should be able to get one for a road test. Right? While we're at it why just one? Why not get one of each kind and compare them? The Mustang and Camaro are obviously on even terms so it didn't seem quite fair to test a Javelin which has had less than a year of development time. We've gone pretty far in saying we're encouraged by the AMC effort, and the plain fact is that they deserve a little time to sort out their car.

What we wanted for this test were cars that any enthusiast could duplicate with factory parts and yet have performance and handling far beyond the sporty cars. Way, way beyond them. We wanted to wander into the office after the test dazed—surfeited. A night with Jane Fonda, a $1 million stake to blow at Monte Carlo, Saville Row to turn out an endless stream of four-button brocaded double-breasted waistcoats. Velvet collars, Moet & Chandon, 320-foot steel-hulled diesel yachts. That's what we wanted. Trans-Am racers for the street.

FIA homologation papers were convincing evidence that each manufacturer had an abundance of high performance parts that would result, if everything was done just right, in a blindingly fast, exquisitely responsive street car. But the only way to be assured of the best combination of these delectations was to have the manufacturers supply the cars. That's where the footwork started.

C/D has been doing comparison tests for a while and in every test, when we find cars we like and cars we don't, we lay it on the line. In a 2-car test, the second place car is also the last-placed car and it didn't take Ford and Chevrolet awfully long to come to just that conclusion. Neither one wanted to play unless they could win. There would have to be rules or we'd end up with Mark Donahue's Camaro and Jerry Titus' Mustang—which would be a complete gas—but would miss the point entirely. It would all be pretty simple: any factory installed or dealer available part would be acceptable if it was homologated. We suggested that the engines have the racing two 4-barrel intake system and tuned headers but mufflers would be used at all times. We wanted only factory-available street tires and we wanted the cars supplied with axle ratios as close to 4.10 as possible since both Ford and Chevrolet had homologated this ratio. Of course any homologated suspension parts would be acceptable and 4-wheel disc brakes would be a welcome addition. We warned that we would be on the lookout for cheaters so the engines had better not be bigger than the FIA 305 cubic inch limit and the cars had better not weigh less than the AMA registered curb weights, not the 2800-lb. Trans-Am minimum. Everybody agreed, shook hands and went back to neutral—and not so neutral—corners.

We had the beginning of a splendidly volatile mix, but we needed one thing more, and that would be Sam Posey. Nothing alive can withstand the magic, probing, X-ray eyes of Sam Posey. A fierce, brave racer who has startled his competitors by his absolute fearlessness—and his almost total understanding of how a car behaves under conditions of maximum stress, not to mention his endless pointed stream of talk about it. Yes, Sam Posey was perfect. In awe of nothing, living everything that separates cars from transportation modules, a driver with brio—and not aligned with any factory team. Everything was set. The very walls of the office quivered in anticipation.

In the succeeding days each manufacturer grew more and more up tight about second-place-being-last. Nervous telephone calls between Detroit and New York were unending. Each was afraid the other was going to build a trick car and put the hurt on his innocent, honest-as-it-can-be street car. They would supply an engineer with their car for adjustments, for keeping everyone honest, and—to our howling disappointment—to return each car to its incubating shop in Detroit the very moment the tests were over.

The first day of testing would be at New York National Speedway where we would do the technical inspection to make sure that nobody had stuffed a 427 or half-thickness steel fenders or any other deceitful devices into our cars.

When we arrived the Camaro and Mustang were already parked, nose to tail, on the strip and much to our surprise, Ford Man and Chevy Man were talking to each other in civil tones.

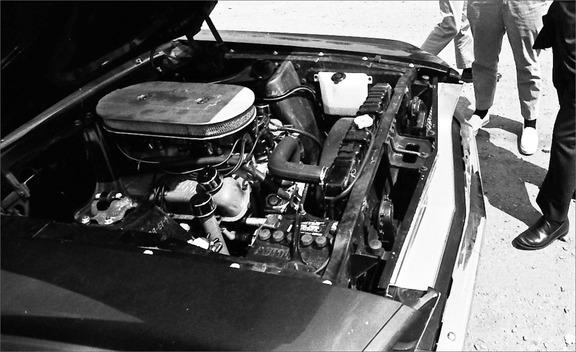

What was going on here? The Camaro was dazzling. All squeaky clean, wearing its black Z/28 hood and deck stripes and front and rear spoilers. Not even any orange peel in its paint. Hell, it was beautiful, but we asked for a street racer, not a contours entry. Up front was the Mustang, looking dusty from the trip, sporting a set of 7-inch-wide American Mag wheels and fat Goodyear donuts the likes of which we'd never seen before. A little rule ingenuity, and we hadn't even started examining the cars yet. Those mysterious tires put over 7.5-inches of rubber on the road and they said "Goodyear" on the sidewalls in great big white letters—just like a race tire. The size marking was F60-15 and the mystery deepened—nobody had ever heard of F60-15 but there they were, big as life. One thing for sure; they made the Camaro's standard E70-15s look like Suzuki tires and we weren't the only ones to notice it. "Uh, I don't know about those tires," said Chevy Man. He'd never heard of their like before. "No problem," said Ford Man leading with the old the-best-defense-is-still-a-good-offense trick. "You can get those real easy. How many do you want?" Along with "how many do you want" he made it clear that, of course, there would be a bill, which slowed us down a bit. What would we do with a bunch of tires that were really too small to be real race tires and yet so big that they would probably rub on the fenders of every street car we could get our hands on? We had no quarrel with their choice of American Mags since the Shelby Mustangs come with 7-inch-wide wheels as standard equipment and the difference between magnesium and steel would never show up in the test. In fact, the Camaro could have used the 7-inch-wide Corvette wheel if they wanted to since it's available through their dealers, but they chose to stay with the standard wheels to emphasize what a good car the regular Z/28 is. "It's a difference in the basic philosophy of the people who built the cars," said Chevy Man later. "They're racers."

The simplest part of the tech inspection was determining weight—so that came first. Our worry about the Camaro being a concours entry was reinforced when the scale said 3480 lbs., 260 lbs. over the minimum.

"I was afraid of that," said Chevy Man. "With the power steering and power brakes and the custom interior it got a little heavy. We wanted to make a nice car but now I'm afraid we'll get drubbed."