Archived Road Test

From the January 1957 issue

Archived Road Test

From the January 1957 issue

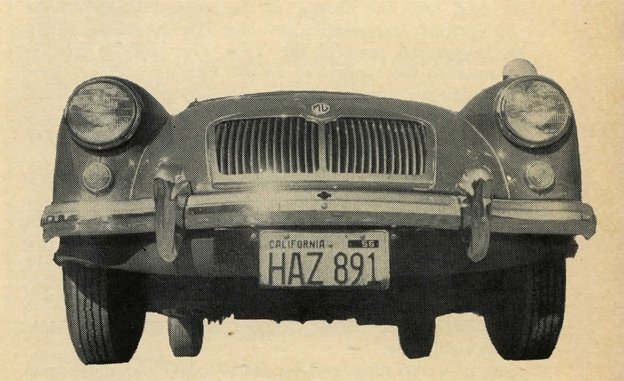

The controversial "aerodynamic" MG is a true 100- mph sports car. Our best one-way speed of 101.1 mph was, to be sure, achieved with the help of a gentle zephyr at the rear, but off-setting this is the fact that we reached the full-century speed in only one mile. With a two-mile approach to the measured quarter, undoubtedly, we would have had a few more revs on the tach and a slightly quicker passage through the traps. What counts is that the "A" is an easy 15 mph faster than the TD, 10 mph faster than the TF1500, and stiff competition for such performance rivals as the Alfa Giulietta Sprint and the Porsche 1600 Speedster.

For most of us, nothing induces a friendly, responsive attitude toward a car—a willingness to be prejudiced in its favor—like a modest price. The "A" is a lot of sports car for its base price of $2195. It's almost entirely new mechanically; the only parts interchangeable with the TF are the steering rack and some front suspension components. Its body is sleek and suave and it has perhaps the first really stiff frame in the long evolution of the little hot rods from Abingdon-on-Thames.

But in spite of all the visible and hidden changes and improvements, you have only to drive the "A" around the block to recognize its old MG character. The engineer who designed the TC's noisy tappets, harsh ride, and loud exhaust system is apparently still bending over the drawing board. In spite of its contemporary look, better handling and thrustier performance, the "A" is still pure old-line MG Midget.

Like its ancestors it's a whole lot of fun to drive in spite of—or maybe because of—its imperfections. The steering as always is very quick over a large lock, and Detroit-conditioned drivers look somewhat palsied at the wheel until they sharpen their responses. Once they do, though, the alert steering naturally makes for excellent control of the machine. This steering is light, has a fairly strong self-centering action and is devoid of play. Minor road shocks are not felt through the steering wheel, but big bumps definitely are.

Another of the organs of the machine that retains the old MG's character is the gearbox. The remote shift lever is ideally at hand; stubby and short in travel, and the synchromesh is infallible. Pumping this lever through the cogs on our 5000 mile-old test car still took plenty of bicep power, but we understand that the transmission begins to limber up after seven or eight thousand miles.

The hydraulically-assisted clutch is light, strong and sure and upshifts can be made with lightning speed. Going down from third to second is slightly awkward and presents the possibility of crunching against reverse or even engaging it while moving forward at low speeds. Nevertheless, this is a good and very satisfying gearbox, despite the fact that low gear is overly low.

The "A's" ride is still another instance of blood telling. It's smooth on smooth pavement, and that's all. The rest of the time it's aggressively hard, in the spartan sports car tradition of the Thirties. Unlike a lot of modern light cars, which not only corner well but also absorb horrible bumps, the "A" and its occupants feel every surface ripple. Beyond about 80 or 85 mph, even on smooth pavement, the ride gets a little bouncy—this, in spite of the fact that a prototype of this chassis was run at better than 150 mph on the Bonneville Salt.

But up to this point the car cruises free and easy and still retains pretty good acceleration. It has a solid, substantial, all-of-a-piece feel that's largely due to the "A's" new frame. The big, box-section rails are tied together by cross-members at something like two-foot intervals and to these are added a box-section superstructure that gives added stiffness at the firewall line. This is a heavy frame but a very stiff one, and because of the reduced weight of the "A's" engine, transmission and rear axle, its chassis weighs just about the same as the TF's. The body is securely mounted to the frame and on the roughest surfaces there is no sign of frame twisting or of body panels "working" independently. The doors close with a solid sound and they stay closed, unlike those on some of the springier-framed MG's.

With a full tank of fuel the "A's" weight distribution is very close to 50-50, and this, combined with the stiff suspension and a close tread/wheelbase ratio helps give the car its well-balanced cornering qualities. Its bite in the turns is softer than the on-rails variety, but it sticks to the road very well—much better than its forebears did. Body roll and tire noise are slight. The rear tires begin to slide only when sorely tempted. and then in a slow, controllable way.

As an accelerating machine the new MG goes much more briskly than the TF, in spite of nearly equal displacement and a 1.2 percent reduction in final drive ratio. Since horsepower and torque have gone up just 4.6 and 1.8 percent respectively, most of the gain in both acceleration and top speed has to be caused by the lower wind drag of the "A's" streamlined body. The acceleration curves of the "A" and the TF show that there's a big difference in the way that these similarly endowed cars penetrate the air.

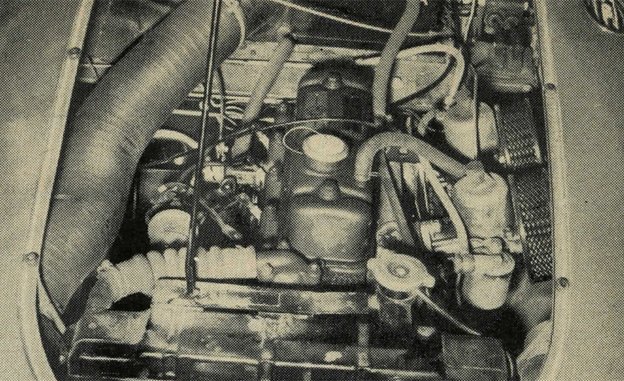

The modified BMC B-type engine is basically the same as the one that powers the four-cylinder Morris, Wolsley and Austin except for its more sporting camshaft and dual carbs. The compact gauze-type air cleaners do little or no silencing and the moan of air being dragged into the cylinders gets really loud at about 70 mph. On the whole this is a pleasant sound, suggestive of gobs of power, but when the weather equipment is up it can get tiresome.

All the porting is on the left side of the engines. There are two intake ports and three for exhaust, feeding into a nicely contoured three-branch "header" type manifold. This style of porting is practically immune to the more advanced forms of intake and exhaust "ram" tuning, but since nobody is more aware of this than the factory, a simple remedy is undoubtedly already on the drawing boards. The throttle linkage is devious.