Archived Comparison

From the April 1977 issue

Archived Comparison

From the April 1977 issue

Five years ago, all the smarties, including those occupying positions of responsibility on this staff, told you that those manifestations of the great performance binge of the 1960s known as Pony cars were as surely doomed to the automotive tar pits as ragtops and side-mounted spares. No one believed these predictions more than the Detroit moguls who read the omens of inflation, energy shortages and the ravings of consumerist loonies as sure death for all performance automobiles in general and Pony cars in particular. Ruthlessly they offed the Barracuda, Challenger and Javelin from the corporate menus while altering the Cougar and Mustang to a point where they were to high-performance motoring what Longines Symphonette represents to the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Suddenly they were gone or transmogrified, and the enthusiasts of the nation—who had not gotten the word that driving for fun was gone forever—puzzled over why everybody had acted with such maniacal haste. They responded in a variety of ways: Some kept their old Pony cars in loving repair; others turned to the few sporty vehicles that remained, hence the booming sales of Corvette, Datsun Z-cars and Porsches. And still others began to buy in ever-escalating numbers the only legitimate Pony cars that, in some bizarre role as an automotive Ceolanth, had defied evolution and had remained in production.

Those cars were the F-bodied sisters from Pontiac and Chevrolet, the Firebird and Camaro, which remained in the marketplace as rather wispy reminders of the old days. Each year, with the exception of the modestly sporty Camaro Rallye Sport and the Firebird Formula, the cars became increasingly aimed at an audience of secretaries and suburban housewives. Only one car of the lot, the Firebird Trans-Am, sustained an unvarnished position as a pure, all-out-hell-for-leather performance automobile.

Why Pontiac chose to keep the Trans-Am around in the face of the retreating competition is of little interest here, other than to note the irony that of all the machines of the species there is little debating the fact that the best of the lot was preserved. (Automotive Darwinism is alive and well)!

The Pontiac Trans-Am turned into a hellishly successful car in the face of all the gloomy sales forecasts. As the years passed it lost some of the brutal acceleration it enjoyed during its 455 Super Duty era, but that lapse in power was more than offset by steady improvements in suspension and running gear that created a delightful American 2+2 Grand Touring automobile. Pontiac stylists were not totally immune to the temptations of littering its splendid contours with increasing acreages of cornball decals, but in general the Trans-Am remained what it was when introduced in its most recent form during the middle of the 1969-70 model year: the sportiest, most roadable four-place automobile built by an American manufacturer.

Then a strange thing happened. In 1976, Trans-Ams began accounting for half of all Firebird sales. The surprise miniboom did not escape the Motor City sales analysts and prompted attempts to cash in on what was considered a renaissance of the performance market. Perhaps the most spectacular—and superficial—effort came from Ford, where the Mustang II was decked out in garish paint and tape combinations to become the Cobra II. Chrysler has made a similarly feeble gesture with its Plymouth Volare Road Runner, while a more legitimate try was undertaken by American Motors and its Hornet AMX.

But these are all stopgaps, designed to plug holes in the model lineup until proper performance machines can be created. Therefore the field was left to Trans-Am in terms of anybody manufacturing a really honest sporting coupe in the mold of the old Pony cars. Until now, that is, when Chevrolet unloads its all-new Z/28 Camaro on an unsuspecting industry and a delighted public.

The Z/28 was last seen in 1974 when the power and speed that emanated from its light, high-revving small-block engine was in a state of seemingly terminal decline. Rather than let the proud name become just another plastic applique on the flanks of various ordinary cars—as happened to the Pontiac GTO and Plymouth Road Runner—Chevrolet yanked the car off the market. Now it returns in a fashion that is sure to blow the lid off the entire world of fast automobiles and end, once and for all, the notion that Detroit and the American public have forgotten performance.

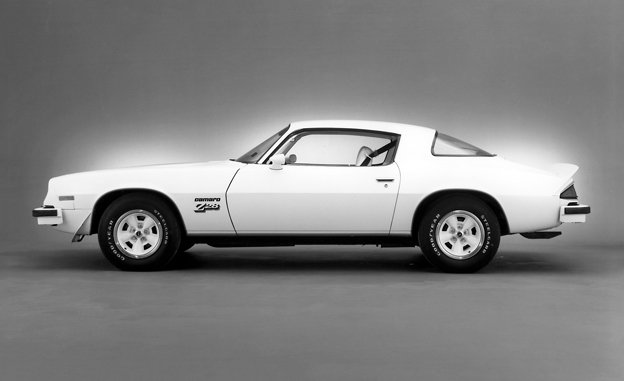

We first encountered the automobile on the flat terrain of General Motors' Mesa Arizona Proving Ground, where it appeared in the proud possession of Jack Turner, the Chevrolet engineer who headed the design team for the Z/28 project. It was hardly a dazzling visual sight, mainly because we were so familiar with the liquid lines of the Camaro after so many years, but the presence of spoilers fore and aft, relatively discreet decal treatment and custom wheels indicated that this was no ordinary machine.

A few moments in the car, with Turner lashing furiously around a small test loop, removed all doubt. "We think this is a pretty special machine," said Turner, a confident, square-shouldered guy who learned to drive—and dig cars—on the convoluted mountain roads around Old Forge, New York. "I wanted a road car, one that was fun to drive, like the Porsche 924. We had a Porsche during the initial stages of this project, and we were really impressed with its handling. But frankly, I think this machine will run right with it." And then he accelerated to 105 mph on a long straight and flung the Z/28 sideways.

The car yawed to the left, its body rolling slightly, its steel-belted tires screeching angrily, then snapped back on course. Turner yanked the wheel hard right, and the car responded with the same precision. "I wanted a car with a lot of linear stability, one that would make really good transitions, both in lane-changing and in hard cornering." After the car had returned to straight-line travel, we noticed that Turner had negotiated both brutal slides with one hand. Perhaps he had something here. But proving-ground running can be deceiving. The surfaces are often billiard-table-smooth or unnaturally rough. Both can give invalid impressions of an automobile, so we fled the compound and headed for a stretch of bumpy, twisting mountain road running northeast away from the ragged collection of gas stations and fast-food joints known as Apache Junction.

There the Camaro revealed itself as a road machine of the first rank. Its 350 V-8 (operating through a catalyst and two small resonators but no mufflers) sang that special, keening song that issues only from good Chevy small-blocks, while the Z/28 blitzed up the canyons and charged over the arroyos. It was as close to being a neutral steerer as any car with a heavy iron engine tucked up front probably can be and could be easily kicked into more gentle oversteer/understeer conditions by easy application of the throttle or brake.

It was a treat for Turner to work on a machine like the Z/28. For the past four years he had been assigned to Chevrolet's new B-body intermediates, and it was he and his fellows who created the "F-41" optional suspension that makes large, solid-axle sedans handle like tiny sports cars. "There is only one way to make a suspension work, and that's out here," he said gesturing at the blurred dirt banks and cactus. "I've worked with computers, and they'll only take you so far. Then you have to get out here and drive'em. You take a lot of cars like this with big front sway bars, and when you drive'em really hard you get bad under-steer and the feeling that the front wheels are doing all the work. I like to feel the rear wheels working too. That's where this car really has an edge."

Did he mean the Z/28 had an edge on the Pontiac Trans-Am, the majordomo in this field? "We're buddies with all the guys at Pontiac," said Turner affably, "but they are our rivals too. Sure, they are interested in what we're doing with this machine, and we've shown'em most of what we've done. But not all of it. We've got some stuff in reserve. We're not finished with this project by a long shot. Wait until you see what we do next year." (Turner's claims for improvement boggle the mind, based on this year's car, although we know the '78 Camaro will use the same basic body. The 1978 Z/28 will have a better-integrated front and rear bumper, plus louvers in the front fenders, a la the new T-Birds and Continentals.)