Road Test

Road Test

Hell being unavailable, we settled for Phoenix. Cursed by a midsummer heat sink featuring brain-frying temperatures, traffic jams reaching all the way to Indio, and enough smog to choke a Cape buffalo, the sweatbox Valley of the Sun was a measurement of our desperation.

But we were willing to go anywhere in search of our prey, a vehicular version of Nessie, a machine that for almost three years had eluded us, coquettishly appearing, then slipping away before our gimlet-eyed techies could determine if, in fact, it measured up to the claims of the legendary man whose name it bore.

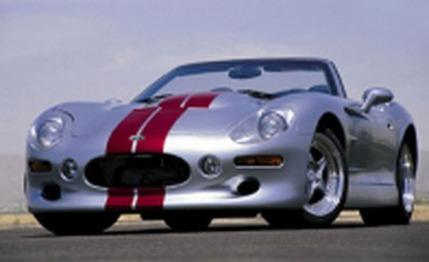

The man is Carroll Shelby, indefatigable automotive icon and creator of the elusory machine known as the Shelby Series 1. From the moment we first reported on the project in July 1994, the car seemed cursed by production glitches that drove Shelby to the verge of apoplexy and, worse yet, threatened to besmirch a legend that spanned a half-century, centering on the Cobra and his great racing career.

And then Shelby telephoned last July. Finally, one of the first of the supercharged versions would be delivered from the Shelby American factory in Las Vegas to Firebird International Raceway at Chandler on the edge of the Phoenix sprawl.

Shelby's Series 1 idea had seemed brilliant: Mate an Oldsmobile 4.0-liter V-8 created for the Indy Racing League to a state-of-the-art chassis overlaid with a featherweight carbon-fiber body, and add a lathering of Cobra mystique. Brilliant, until it was determined that the IRL engine was too specialized for federalization, and rather than an anticipated 370 horsepower, the alternative powerplant, an Aurora production-based DOHC V-8, would pump out just 320 horses. Complicating that, intense internal opposition surfaced inside GM, reaching a peak when Oldsmobile boss John Rock, a major Shelby supporter, cleaned out his desk in 1996.

Early Shelby prototypes were not only anemic under the hood but were nearly 700 pounds over the projected 2650-pound target weight, owing to the inferior quality of carbon-fiber body panels and a heavy retractable top that refused to work properly. Yet the basic package, featuring a floorpan, rear bulkhead, and rocker panels fabricated from space-age aluminum honeycomb, plus sophisticated rocker-arm, coil-over suspensions front and rear, a six-speed transaxle (built by RBT in Austin, Texas), big vented disc brakes all around, and a 49/51 front-to-rear weight distribution, implied that the Series 1 had all the right stuff, at least on paper.

A modest network of 15 dealers was created, and about 50 early Series 1s fitfully drifted off the Las Vegas assembly line in 1998 and '99 amid rumors that the project was terminally ill. Many orders for the car -- about 225, some sources said -- had been placed and deposits of $25,000 taken against the car's declared price of $99,975. By September 1999, that sticker had escalated to $134,975, and now, due to unexpected costs of production, the price of the base model -- the one that is not supercharged -- is $181,824. (The supercharger package is expected to add just under 20 grand.) At 77, Shelby was battling health problems and was brought almost to his knees by the quality debacles and the threat of lawsuits from angry customers (see Upfront, June 2000).

Then late last year, Larry Winget, the owner of Venture Holdings Company, a $2.3 billion supplier of carbon-fiber body pieces to the global automotive industry, stepped in with financial help (a reported $10 million), plus technical and administrative assistance. Thanks to the infusion of capital from the firm based in Fraser, Michigan, the Series 1 got back on track. In the past six months, production has steadily ramped up to the planned two-per-day quota and toward a maximum build of 500 cars. Venture's body panels appear to be excellent, and thanks to Dura, the same firm that fabricates the Chevrolet Corvette convertible top, a light 37-pound workable top has been created. (It will be retrofitted to the topless Series 1s delivered to early customers.)