Road Test

Road Test

In his 1975 indictment of modern art, The Painted Word, Tom Wolfe noted that the modern art world had become completely literary; paintings, he said, existed only to illustrate an idea or the theory behind the piece. Artists were, said Wolfe, engaged less in representing reality in a beautiful or accurate way than they were in competing in a game of intellectual one-upmanship.

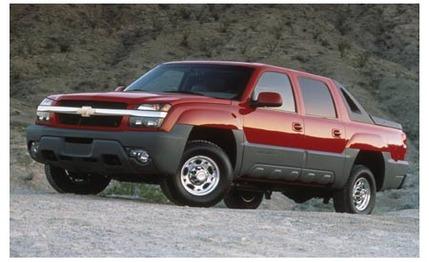

This was on our minds every time we drove the half-pickup/half-sport-ute thing called the Chevrolet Avalanche. It's certainly not a calculated insult, as Wolfe would describe modern art, against middle-brow tastes. But the Avalanche is about something. It's the idea of "convertibility," "spontaneous adaptability," and "ultimate utility" rendered in 5820 pounds of steel and plastic.

At the center of the Avalanche, both literally and figuratively, is the "Midgate"-a piece of high-strength plastic 53 inches wide and 25 inches high that acts as the rear wall of the vehicle's cabin and the front wall of the cargo bed. The Midgate is hinged on its bottom edge so it can be opened like a trap door between the cabin and the bed.

The Midgate is the engineered manifestation of the desire to allow free flow between the inside and outside of the vehicle. This would be where that "spontaneous adaptability" part comes in. When it's latched shut, the vehicle is a five- or six-passenger sport-ute that has a small pickup bed in back. Open the Midgate, and the Avalanche is a two- or three-passenger (depending on whether it is equipped with front buckets or a front bench seat) pickup with a full-length bed.

To open the Midgate, first fold down the 60/40 split rear bench seat, then turn a latch, and the gate falls flat on top of those folded-down rear seats. It extends the cargo bed into the back half of the cabin, turning a short, five-foot-three-inch-long box into an eight-foot-two-inch-long truck bed.

And that was just trick one. Release two latches at the trailing edge of the headliner, and the rear glass comes out, independent of the Midgate. It stores away in a recessed area on the Midgate. You can remove the rear glass separately, or you can fold only the Midgate, leaving the glass in place. Or you can open the entire rear of the cabin by removing the glass and folding the Midgate.

A horizontal crossbar between the glass and the Midgate stays in place to support the glass if you wish only to lower the Midgate, or it folds forward with the Midgate. It's a clever device that gadget freaks will love.

Whether anyone needs such a device is immaterial. It's the idea, man, an idea that we first saw on the Nissan SUT concept a few years ago, although fiscal uncertainties precluded the company from developing it.

The Midgate is the only critical difference between the Avalanche and the herd of four-door pickup trucks that have poured into the market in the past few years. Without that Midgate feature, the existence in Chevy's truck lineup of both this vehicle and a four-door Silverado doesn't make much sense.

But for all its cleverness and good execution, the Midgate doesn't add any cargo- or human-hauling capability beyond that of a four-door pickup with a bed extender. The real advantage of the Midgate solution might have been to prevent the Avalanche from becoming grotesquely long. Although it provides plenty of room for up to six passengers and eight-foot-long loads (but not simultaneously), the Avalanche is about two feet shorter than a full-size four-door, crew-cab pickup. But at 18-and-a-half feet long, it's not compact, only less massive.

There are other clever ideas, such as a three-piece hard bed cover. Combined with the standard locking tailgate, the cover also provides a secure, enclosed cargo hold. Chevy also made enough room inside the wide cargo-bed walls for a small, lockable compartment on each side that can be used as ice chests.