Feature Test

Feature Test

Caterpillar’s new D7E bulldozer is the world’s first hybrid—uh, electric . . . uh, wait, what is it again? “We consider this a diesel-electric hybrid powertrain,” says senior project engineer Keith Heiar, “but we’re not labeling it with the ‘hybrid’ word on the side of the machine.” That’s because, although the company’s first-ever electric drivetrain is the greenest thing in the stable, it doesn’t have auxiliary battery storage and therefore doesn’t fit the category as defined by the automotive world.

Among Caterpillar’s almost 30 different categories of machines, the D7E belongs to the rather clumsily alliterative and repetitive “track-type tractor” unit; these are commonly referred to as “dozers.” This type has a long history, dating back to the formation of Caterpillar Tractor Co. in 1925, and still produces one of the biggest chunks of revenue for the world’s largest maker of construction and mining equipment.

This 60,000-pound D7E—that’s as much pork as 10 Range Rovers—is about six inches longer than a Chevy Suburban (including the blade), but it’s more than nine feet wide. In Caterpillar’s lineup of dozers, the D7E fits roughly in the middle; at the light end, there’s the 17,000-pound D3, which might be used for small commercial construction, and at the other end, there’s the mammoth D11, an intimidating 250,000-pound brute built for mining work, with a nine-foot-tall blade and nearly seven-foot-tall tracks.

The company says the D7E project involved almost 500 engineers over the course of roughly a decade to produce this completely new dozer with the first-ever electric drivetrain. But somehow they still arrived at exactly the same paint scheme as before: uniform dull yellow. However, customers can choose custom colors; for example, did you know that machines destined for landfills are often painted blue? That’s done in an attempt to fool birds into thinking they’re looking down at water. Apparently they prefer to launch their sloppy missiles onto land, and this tactic reduces the amount of guano spattering dozers.

Compared with the similarly sized, conventionally powered D7R Series 2 that it replaces, the D7E’s overall performance is up 10 percent, which is measured by how much material can be pushed in an hour by its blade—it’s five feet high and 13 feet wide. At the same time, the new dozer’s electric drivetrain consumes 25 percent less fuel, thanks in part to a downsized diesel engine and the elimination of the efficiency-sapping torque converter and three-speed manual gearbox, which it no longer needs. Still, in full-on work mode, the D7E consumes fuel at a rate of five to nine gallons per hour, which is why it comes with a tank as large as 126 gallons.

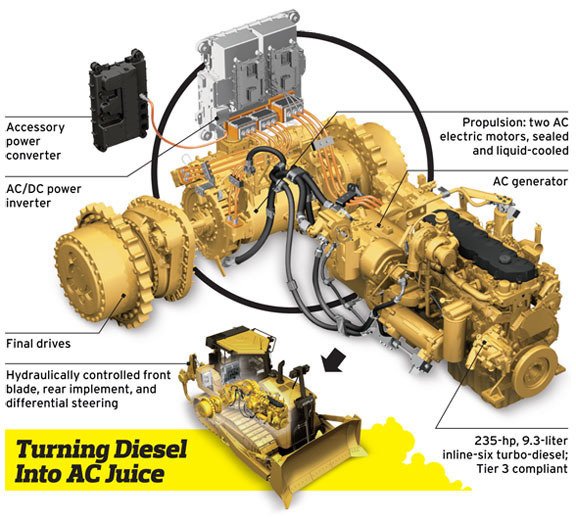

The engine is a turbocharged diesel—a 9.3-liter inline-six that makes 235 horsepower. Though huge, it’s a liter smaller than the unit in the D7R, and—for the first time—it isn’t mechanically connected to the tracks. Instead, it turns a generator that creates as many as 330 amps of AC electrical current at 480 volts. The electricity is converted to DC for use by the accessories—such as the engine’s water pump, the cabin lighting, and the air conditioning—which contributes seven percent to the overall efficiency improvement. Meanwhile, AC current propels the dozer via two huge brushless electric motors that measure more than a foot in diameter, are about two feet long, and weigh roughly 600 pounds each. Combined, they produce 215 horsepower and an undisclosed amount of torque that’s probably in the neighborhood of 1500 pound-feet. This arrangement is similar in concept to that of a locomotive, although Caterpillar has developed this particular proprietary system in-house to meet the demands of a work site. These requirements include: frequent changes in direction; climbing 45-degree inclines; and being able to slog through mud, water, and garbage. That’s why, in this case, all the electric components are fully sealed and liquid-cooled. And despite all the heavy electronics, the D7E actually weighs about the same as its conventional predecessor.

Imagine what might be created by a group of entrepreneurial toddlers seeking to build a 720-acre version of a sandbox, and you’ll have a pretty good idea what Cat’s Edwards Demonstration and Learning Center is all about. Located roughly 20 miles from the company’s headquarters in Peoria, Illinois, it’s a veritable playground for the company’s machines and where we got a chance to pilot the D7E. The facility features numerous outdoor areas with a variety of different materials—dirt, sand, rocks—in which to demonstrate capabilities, but we spent our time fluttering in the larger of two indoor facilities. This is basically a gigantic two-acre warehouse, complete with a glass-enclosed viewing area that allows spectators to look on in climate-controlled comfort as Caterpillars assault the earth.

First, operator Bob Powers, who has 1000 hours of experience at the helm of the D7E, gave us a brief primer. The three-pronged thing attached at the rear of the dozer that looks like Freddy Krueger’s bad hand? It’s called a ripper, and Powers does just that to the ground and then starts getting serious with the blade. In less than 10 minutes, he’s exhumed a pile of dirt at least as large as the D7E itself, and then we are treated to a little showmanship as he coaxes the dozer up the side of the dirt mound and performs a pirouette at its summit. Then, in roughly the same time it took to create the crater, he fills it in once again.

We are slightly less smooth. To reach the cockpit, step up onto the bottom blade support and then up onto the left track, grab the handle, flop yourself into the cab, and shut the door. The seat is air-cushioned like a semi’s and adjusts fore and aft, offering plenty of room for six-foot-five me. Directly in front is the mother of all blind spots because the cab’s single center post is aligned with the exhaust, the air intake, and the lift cylinder for the blade. But Cat designed this new layout to increase overall visibility by 35 percent, particularly at the sides where the edges of the blade are easily seen. Still, it’s like trying to dance with your girlfriend with her stripper pole in the way.

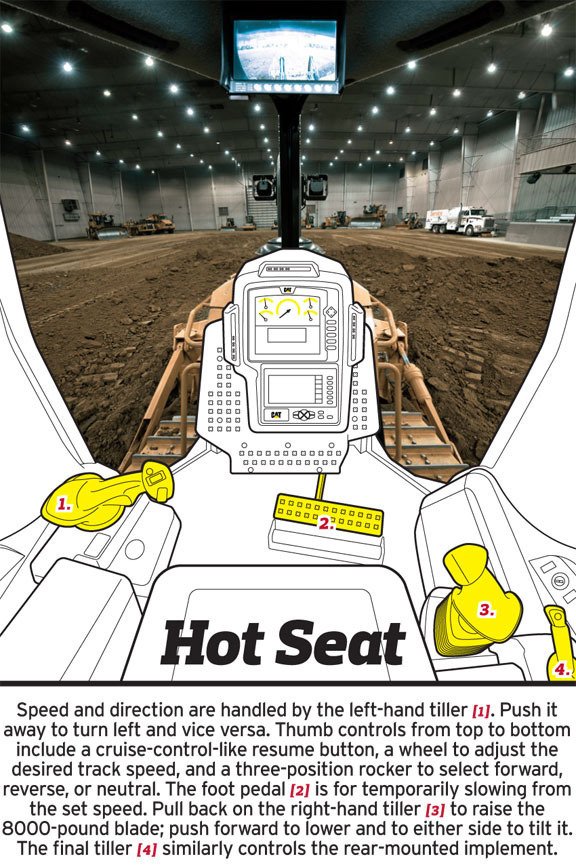

Twist the key, and the big diesel chugs to life. Then turn a knob to bring it up to its 1700-rpm operating clip. The fact that the D7E runs at a relatively constant engine speed, rather than revving up and down through a manual gearbox, is a major contributor to its claimed 75-percent reduction in interior noise compared with its predecessor. At idle, the interior racket is equivalent to a modern car humming along at 70 mph, and even when making the D7E flail, we weren’t wishing for earplugs. The tiller on the left controls steering, speed, and direction. Pull it toward you to turn right, and push it away to go left. Set speed by a thumb wheel and modulate it with a foot pedal; switching directions simply requires a flick of the three-position rocker switch [see below].

Power delivery is via something like a seriously scaled-up bicycle sprocket, except there are two of them, mounted in the rear. What would be the chain are links—made up of two pieces of steel side by side, each almost a foot long and an inch thick—attached to the underside of the tracks. We fully believe Cat’s claim that the D7E can reach its 7-mph top speed—which, incidentally, is plenty; we’ve experienced few single-digit velocities as hairy—in just 4.5 seconds. And the weighty track assemblies seem to strike upon a natural frequency as that speed is approached, causing them to slap loudly over their guides in what sounds remarkably like a dozen horses clomping by.

Most striking from the cockpit is an overwhelming sense of awe at the forces at work here. How can this 30-ton behemoth be so uncannily responsive to the directional tiller, practically leaping at any ordered course changes? Flip the switch from forward to reverse, and it takes but a couple seconds for the electrified beast to slow down, pause momentarily, and accelerate in the opposite direction. Awesome also applies to the forces that can be passed along to the operator, such as when we backed out of a hole a little too rapidly, causing the dozer’s tracks to slam violently to the ground and doubling us over the lap belt in a jolting appreciation for the amount of mass that we were commanding.

And digging is a whole other matter; we repeatedly tried to push too much dirt—the D7E’s blade can move roughly 1200 cubic feet of material, or as much as found in the cargo holds of 80 VW GTI hatchbacks—and wound up spinning the D7E’s tracks fruitlessly. Performing this correctly requires constant and subtle changes to the right-hand lever that controls blade height in order to avoid overdoing it.

The electric drive system also gets credit for 50-percent better maneuverability, mostly because the D7E can do both stop-track turns, in which one track comes to a complete halt while the other pivots the dozer around, as well as even more immediate counterrotating turns wherein the two tracks spin in opposite directions. Backing up that claim is the way in which our extremely inexperienced hands were able to make the D7E dance through a slalom course without much trouble.

So what’s not to love? Better maneuverability, more capability, less fuel consumption—and it’s easier than ever to operate. Plus, the D7E has fewer moving parts, accounting for longer service intervals and reduced maintenance costs. Well, like most new technologies, it’s not cheap, and the base price of $600,000 is about a 20-percent hike over its predecessor’s, although Caterpillar claims the extra cost can be recouped via fuel and maintenance savings in just two and a half years.

Call us juvenile, but—although technically impressive and an environmental milestone in the world of heavy-duty equipment (the D7E won a Clean-Air Excellence Award from the EPA)—after witnessing both the ground-shredding ripper and the dirt cascading off of the tracks during a counterrotating turn, we couldn’t shake visions of enacting the world’s most spectacular lawn job. In just five minutes, the D7E could send an unmistakable message to that intensely obnoxious neighbor—or maybe to an ex—that might otherwise take years of sarcastic exchanges. How’s that for a productivity improvement?