Instrumented Test

Instrumented Test

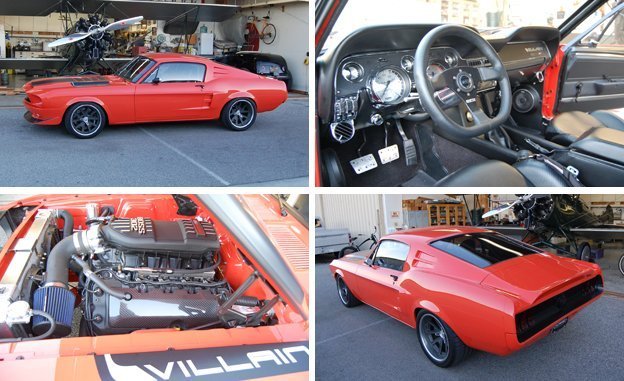

There’s nothing wrong with old cars except the fact that they’re old. Bodies rust, suspensions creak, and most engines eventually eat themselves. Ford Mustang specialist Classic Recreations in Yukon, Oklahoma, has a solution—albeit an expensive one—for those who want a ’68 fastback with an invigorating dose of modern vitality: the Villain, by CR Supercars. This reborn Mustang has substantial body changes, a new suspension, a 5.0-liter DOHC Coyote V-8 from today’s Mustang, and upgraded everything else. It takes curves with all the unflustered aplomb of the last-generation live-axle Mustang yet retains the vintage cool of the much older, pre-everything pony car.

The idea is assembly-line custom hot rods, says company owner Jason Engel. You can have it any way you like it, whether that’s as a caged and Procar-bucketed track rat, as a highly original-looking stocker with the modern bits hidden, or any combination thereof. But the one thing the Villain isn’t is old. “I wouldn’t want to stick a 550-horsepower engine into a 40-year-old car and hope it holds together,” says Engel, referring to some of the higher-horsepower Shelby reproductions the company makes.

A Villain can start one of two ways: built up from the $17,500 reproduction body offered by Dynacorn Classic Bodies in Camarillo, California, or from an original ’68 donor car. If you go the latter route, Engel prefers rusty basket cases to solid cars, as so much of the metal is swapped out and reinforced in the build anyway.

Dynacorn versions (like the prototype pictured here) get a new hood, rocker panels, decklid, headlight surround, and lower nose, all of CR’s own design. All four fenders are widened a bit at the arches to make fatter tires fit better, and the taillights and rear panel are born from an exhaustive process of shaping metal and plastic to look just so. About the only things that come right out of the box are machined door handles from Ringbrothers and California Pony Cars mirrors made special for the Villain.

Customers must wait 12 months for their car. The reason is because everything takes so much time, says Engel, including the custom fabrication of the knockoff spinners for the 18-inch Forgeline wheels, which is done locally in Oklahoma. There are also further body modifications to accept the Detroit Speed Quadralink rear suspension, which replaces the old live-axle/leaf-spring setup with four leading links, a Panhard rod, an anti-roll bar, and coilovers; this process takes a month alone. Likewise, the front suspension by Detroit Speed replaces those old Falcon struts with a primarily aluminum module that includes an aluminum front crossmember, forged spindles, tubular upper and lower control arms, and coil-overs with toothed camber/caster adjustment.

The cornering is astonishing for a car that otherwise looks so vintage. It feels every bit as capable and composed as the last-generation Mustang, tracking flatly through fast bends with a sharp bite to the steering. Downshifts are a joy as the V-8 snarls and the car tucks in for the turns. The weak point in our car was the brakes, which offer a firm, unboosted pedal but not much arresting action and no ABS. Indeed, at 292 feet, the stopping distance from 70 mph was school-bus-towing-a-semi-truck atrocious.

The engine in CR’s Bad Guy Orange prototype is a Ford Racing 5.0-liter Coyote crate engine, which is rated by the shop at 475 horsepower. It’s basically a more powerful version of the 435-hp engine in today’s Mustang, and it bolts to a Tremec six-speed manual and a nine-inch Positraction limited-slip rear end. The setup posted a zero-to-60 time of 4.5 seconds and a quarter-mile of 12.9 at 112 mph, about the same as a 2015 Mustang GT. This Villain might have been quicker but for massive overkill on the tire selection (335/30s in back!); these are great for 645-hp Vipers and for cornering, but they just add rotational weight to launches.

As we said, the Villain is not cheap—$154,900 as pictured here—and there’s that one-year wait. But the cost is comparable to a proper 100-point restoration of an original these days, which, when completed, will give you a car with floppy body stiffness and a point-type ignition. Our prototype was knocked together for the SEMA show with casual attention to panel gaps and fitment. A silly, small Sparco steering wheel looks out of place in the otherwise retro interior, and the machined interior door-latch releases were finger biters. No doubt, Engel and his team have experienced a learning curve as they try to make 1968 better than it ever was.