Instrumented Test

From the October 2015 issue

Instrumented Test

From the October 2015 issue

We have only fond memories of the original Chevy Volt, that slab-sided toccata and fugue of Yankee ingenuity from 2011. It looked like something Jimmy Carter acolytes created after locking themselves in a bunker with a Commodore PET computer, the Tupperware collection for 1981, and a laserdisc of the movie Tron. But the Volt worked, delivering both electric-vehicle stealth and internal-combustion freedom. It may have missed the energy crises for which it was perfectly suited, but its timing was still propitious. The 77,000 or so units that Chevy sold, the majority in California, thoroughly expunged the mark of Cain borne by General Motors ever since it was accused of killing the electric car.

The Volt II proves that GM’s novel idea for an enviro-hybrid has cleared the tower of experimentation and is on full-powered ascent into a regular product line with a history and a sustaining business case. Could we finally see the Volt give birth to a family of vehicles—at least, besides a Cadillac coupe? Given the public’s current fascination with small crossovers, surely GM must have a little SUVolt in the works.

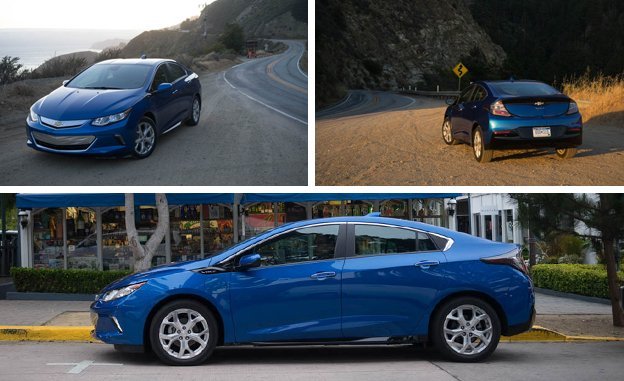

Either way, the new Volt’s styling makes a 30-year thematic leap to contemporary windswept sensuality, and the interior is no longer something out of the Apple catalog c. 1999. The silly touch-sensitive capacitive controls are gone, replaced by a mosaic of conventional push buttons set in a pleasingly organic fan of interior plastics and complemented by an elegantly integrated infotainment screen.

No doubt some Voltifosi will lament the car’s reach toward design normalcy, toward looking a lot more like a Honda Civic. But the car both looks and functions a lot better, especially since GM makes a terrific effort to cater the car’s controls to the needs of EV buyers and especially their hypermiling radical elite. And Volt lovers can rejoice that the basic four-door-hatchback envelope is essentially unchanged, with just about a half-inch inserted in the wheelbase and 3.3 inches added overall, mainly for styling and to give rear-seat passengers a little more legroom. Indeed, the frontal area and claimed drag coefficient of 0.28 are essentially as they were before.

While the car grows, its weight shrinks, our loaded Premier tester tallying 3396 pounds against 3766 for our last Volt test car. That triumph means the Volt effectively eliminates the mass gap with its arch rival, the Toyota Prius plug-in, and greatly narrows it against the regular Prius. Much of the Volt’s excess cottage cheese came off the electric drive unit (99 pounds) and battery pack (31 pounds), which is where the most-profound changes to Volt II are found.

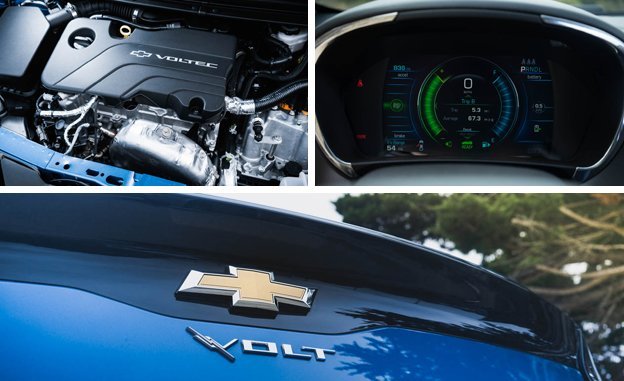

GM’s marching orders from its customers were clear: Give us more range in EV mode, make the engine quieter, and give the car more driving spunk. The old powertrain, which paired an iron-block 1.4-liter four-cylinder to one large propulsion/regen motor/generator and one smaller multipurpose electric machine, got a complete rethink. Now, a more powerful Atkinson-cycle 1.5-liter aluminum-block engine works in concert with two smaller motor/generators, housed inside a transaxle to drive the differential through a chain rather than gears as before.

Engineers studied a range of engines, from a 1.0-liter turbo three-cylinder to the 1.5, and selected the largest because of a fact that Corvette owners have long known: A bigger engine turning more slowly can be remarkably efficient. And quiet. And quicker, if need be, since the bigger engine doesn’t need to call on the motors as much when the driver floors it. The long, 86.6- millimeter (3.41-inch) stroke makes the Volt’s lump a sort of automotive tugboat engine, a low-speed torque machine with its 101 horsepower arriving at just 5600 rpm.

A T-shaped battery pack still lies under the tall center tunnel, but its capacity climbs from 17.1 kWh to 18.4, with fewer but larger liquid-cooled prismatic lithium-ion cells to generate more power from a lighter but slightly larger package.

The new transaxle houses two electric motors with 31 percent less combined power and 28 percent less torque than before, three clutches, and two planetary gearsets. Five propulsion modes are available. As long as energy is available from the battery pack, the Volt drives on one or both electric motors. When the charge is depleted, one of the motors cranks the engine to begin extended-range operation. Manipulating the clutches provides three distinct ranges for accelerating, cruising, and high-speed driving, with the motor/generators participating in propulsion and battery-charging roles. As in the original Volt, the electric motors also charge the battery during deceleration (regen).

Chevy claims a 19-percent reduction in the zero-to-30-mph time; that jibes with our measurement of 2.6 seconds for the new car versus 3.2 seconds before. The old Volt took 8.8 seconds to hit 60; the new Volt takes 7.8 seconds. The original was said to provide around 40 miles of electric driving; Volt II comes with a 53-mile claim. In two complete drains of the battery during normal driving, we saw 52 and 56 miles. Unfortunately, GM wouldn’t leave the car with us long enough to get a thorough fuel-economy test. Further testing to follow at a later date, but, as you know, the Volt doesn’t yield a simple fuel-economy number because it depends entirely on the way you operate it.