Unfortunately, there's no pat answer as to exactly how large of a turbo you need for any particular sized engine, 1.6L or otherwise. In many ways, turbochargers are entities in and of themselves; the gas engine to which they are attached is almost ancillary in function. This makes turbo selection a matter of setting goals and building the engine to handle it. Whether your 1.6L engine comes from BMW, Nissan, Mercedes or even Peugeot, enhancing power with a turbo is mostly a matter of setting realistic goals and choosing the right parts. Power limitation is, for the most part, determined by your budget and the engine's inherent strength.

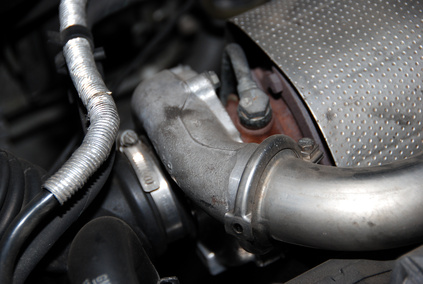

Take a close look at any turbo and you'll find a turbine blade inside of a snail-shell-shaped housing, feeding air into the engine and receiving power from the engine's exhaust gases. Both in terms of form and function turbochargers by themselves are little more than a single combustion chamber away from becoming a true jet engine, according to Junkyardjet.com. As such, think of any turbo engine as a sort of hybrid.

The gas engine exists primarily to convert the pressure of exploding gasoline into rotational movement, which drives the car. The turbocharger itself actually dictates airflow (which determines how much fuel the engine can burn) and maximum power output at anything past idle.

Because the turbo is the primary power-maker, power levels can vary wildly independent of engine size. For example, a small 1.6L turbo might make as little as 70 horsepower. During their 2005 Dynojet Horsepower Challenge, dynamometer manufacturer Dynojet recorded an astonishing 700 horsepower from one turbocharged Hayabusa motorcycle engine, which actually came in at 1.3L in displacement, according to Gizmag.com. The difference between that 70 horsepower engine and the 700 horsepower Hayabusa is partially a matter of engine design, but mostly comes down to turbocharger size.

Since engine size (be it 1.6L or any other) clearly has little to do with absolute horsepower potential, you'll need to use desired horsepower itself as your primary turbo shopping criteria. Generally speaking, a turbo will make plus or minus 15 percent of a given power level regardless of the engine. For example, a Garrett, IHI or Mitsubishi T4 turbo on a 1.6L might be good for 400 horsepower on most engines, but observed power may vary between 340 and 460 depending on engine design and efficiency.

The limiting factor for engine power is how much fuel the engine can burn and how well the engine itself will withstand the punishment. To get huge amounts of horsepower from a 1.6L engine, you may need to replace the pistons, connecting rods and crankshaft with stronger forged aluminum and steel units, and beef up the cylinder head seal with head studs and an O-ringed gasket. Really extreme applications will require engine block strengthening (with a main stud girdle or machine work and reinforcement), or possibly an entirely new block.

If using a small engine has any really serious drawback it's that the engine won't produce enough exhaust gasses at low RPM to get the turbo spinning. This will result in "boost lag," or the tendency to produce power only at very high RPM. You can help to compensate for the engine's small size by using a "hybrid" turbo like the popular T03/04. Hybrid turbos use large capacity compressors for big airflow, and small diameter exhaust-side housings to increase low-RPM boost response.