Most people call them "air bumps." The racing industry refers to them as "secondary suspension." An accurate description for them would be "pneumatic bumpstops." In desert racing, they are required equipment for their ability to dissipate energy, but they've never been available to the consumer in bolt-on kit form-until now.

Light Racing, which calls its units "Jounce Shocks," now offers a kit for '01-and-newer GM 1/2- and 3/4-ton pickups. Originally developed by Light Racing for the U.S. Military to help inexperienced soldiers maintain control of their vehicles during high-speed desert maneuvers, these little cylinders provide significant improvements in suspension damping, allowing a driver to keep the tires planted on the ground, even at excess speeds.

Before we get into the technical explanation of how the Jounce Shocks work, here are some basics of suspension function.

With any suspension system, there are four positions in the range of movement. The first is the compression stage. As the vehicle encounters a variation in terrain, the compression cycle begins. As the energy is absorbed by the springs and shocks, the axlehousing-or A-arm, in the case of IFS-moves upward until it reaches the second position in the cycle: the point of maximum compression, or the "bump" position. At full compression, your vehicle's suspension can no longer dampen the energy of a bump. Most vehicles are equipped with rubber bumpstops, which act as last resorts to lessen the impact between the suspension and chassis during the bump stage. In most cases, OEM bumpstops do a decent job. However, when excess compression occurs, the energy travels right through the rubber block and continues through the chassis. This is the part you feel in your back and typically followed by an expletive.

Following the compression stage is the third position, called rebound. This is what the suspension must do to dissipate the energy absorbed during compression. The rebound energy correlates directly to the energy of the compression and is again controlled by the shocks. The more energy that is stored in the spring during the compression stage, the more energy must be relieved by the rebound stage. If the shocks fail to dissipate all the energy contained during the rebound cycle, the excess energy tries to force the wheels downward, often causing the vehicle to bounce off the ground. This is not a good thing because when tires leave the ground, control is lost.

This leads us to the final stage of the cycle: droop, which is the opposite of bump. At full droop, the suspension is extended as far as it can go. Typically, the shocks or springs dictate the position of full droop. During a high-energy event, the excess force exerted at full droop can be noticeable and is properly characterized as "topping out."

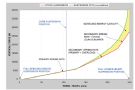

The Jounce Shocks begin working during compression. As a fixed-containment air spring, the Jounce Shock can convert a tremendous amount of mechanical energy into heat. The effect is virtually transparent until the suspension system reaches the 3/4-compression mark. At this point, you would normally raise your shoulders and squint in anticipation of a hard bottoming-out, but instead the Jounce Shock piston compresses a cavity of nitrogen and quickly transforms the would-be violent energy into heat, thus reducing the harshness of the impact. The graph below illustrates these forces with and without the Jounce Shocks installed.

Light Racing developed two different Jounce Shock kits for the consumer market. One is completely bolt-on for '01-and-newer 1/2-ton GM pickups. The other kit, which requires some drilling and welding, was designed for 3/4-ton GMs of the same vintage. Our test vehicle was an '05 GMC 3/4-ton with a Duramax engine.

Once the alignment arm was in place, our installer, Travis, moved on to the upper Jounce Shock mounts. This step required the removal of paint from an area of the frame between the shock bucket and the upper A-arm pivot point. This would provide a clean surface to which the upper Jounce Shock mount could be welded. It is recommended that a skilled welder complete this step as spatial constraints limit welder access, and a great deal of force relies on the integrity of these welds. Here is the bracket just before it was welded to the frame. It comes with a special weldable primer coating to prevent rust prior to installation. This bracket is easy to line up because it has an exact fit to the concave contour of the frame.

Shortly after our test session, we took a ride in one of Light Racing's Jounce Shock-equipped 1/2-ton Chevy pickups. Needless to say, our jaws dropped when the company's vice president, Bryan Kudella, skied the vehicle without drama. We were amazed with the vehicle's ability to soften a landing that would normally destroy the bumpstops of any stock suspension. The best part was when he asked if we wanted to do it again. Bryan continued jumping the truck for us until we'd had enough. After more than a dozen jumps, there was no evi dence of damage to any part of the OEM suspension. The Jounce Shocks did their job.

Another product Light Racing developed for the Military that we thought worth mentioning is its new RokArmor skidplate system. It fits all '01-and-newer GM 1/2- and 3/4-ton pickups. The system uses high-strength 6061-T6 aircraft-grade aluminum to protect the vehicle's vital components. It does require some drilling, but it protects everything from behind the bumper to the transfer case. The RokArmor system has a steel subskeleton support structure that allows jacking from any given point of the skidplate. The kit takes a few hours to install, but is second to none in quality and ground clearance.