Fred Williams

Brand Manager, Petersen’s 4Wheel & Off Road

Fred Williams

Brand Manager, Petersen’s 4Wheel & Off Road

Two hundred and fifty million bucks is a lot of money, but it is also the low side of what General Motors invests in designing, engineering, and testing its front 4x4 suspension. So when you, me, and the guy at the local 4x4 shop start bench racing about the best way to lift your late-model GM truck, we must first realize that we are going to be taking that $250+ million and tossing it in the quest of better ground clearance, and hopefully off-road performance. Of course, GM spent that money looking primarily for ride quality and cost with strength, longevity, and off-road ability further down the list, so it's only appropriate that we would want something different.

Many good suspension lift kits are available for IFS GM trucks, but choosing the right kit for your vehicle is dependent on what type of wheeling you want to do. Basic on-the-road driving requires a safe suspension that won't twist off under high-speed braking, or cause excessive steering issues, and hopefully not require realignment every few months. Basic trail riding and mud bogging are possible with most kits; however, going to tires larger than 35s will put more strain on the kits. Desert prerunning and high-speed jumping demand a kit that allows plenty of travel, and good shocks to control that travel. If severe rockcrawling is your game, then IFS can quickly become a hindrance and you may want to consider going to a solid-axle swap instead.

General Motors implemented an independent front suspension (IFS) in a 4x4 with its foreign-built LUV pickups in the late 1970s, and GM then started building IFS with the 1981-1982 S-10 pickups and Blazers. At around the same time, GM's fullsize trucks with a leaf-sprung solid-axle suspension had horrendous ride quality compared to Ford's coil-sprung trucks, and when GM realized that only a few of its 4x4s were actually being driven off road, the company decided to install IFS in its fullsize 4x4s starting with the 1988 1/2-tons.

To this day the basic IFS design is the same for all GM 4x4 trucks. A front differential is attached to the frame, and attached from the ends of its housing are halfshafts with constant velocity joints that run to the knuckle. This allows each front tire, wheel, and knuckle assembly to move independently. The steering knuckles are supported by upper and lower A-arms that run perpendicular to the framerails. Unlike some other manufacturers, GM always places its upper A-arm on the outside of the framerail; this allows for a wider track width without a severely long A-arm.

When the IFS Chevys and GMCs first came out, the most common suspension kits offered used drop brackets to lower the upper and lower A-arms. These drop brackets required cutting off the factory bumpstop brackets, and then hanging the upper A-arm brackets from the factory mounts so that the upper A-arms were still the same distance from the lower arms, thus using the factory knuckles. This design keeps the factory geometry of the A-arms, axle halfshafts, and scrub radius. However, these kits also require some sort of drop bracket for the steering, and have a habit of often needing realignment. Adding a second bracket to the stock bracket means these kits put more stress on the original components, and in a way they were not designed for.

Eventually the price of doing castings dropped, and suspension companies began designing new kits that included a taller steering knuckle. This allowed the use of the factory top A-arm and upper frame-mounting points, as well as stock steering, while dropping the lower A-arm and the factory differential. However, in order to keep a near factory geometry of the suspension, the lower A-arms must not only be moved down, but also out, and this requires longer halfshafts. We do not know of any kits that include longer halfshafts, but there are many that include aluminum spacers that in turn lengthen the axles by pushing the mounting point of the halfshafts outwards. These kits can give your truck a slightly wider front track, and if larger tires are used, they may hit the fenders due to the wider track. Also, if the geometry of the new knuckles is not perfect, they can affect ride quality, steering components, and steering ability. As with any upgrade we recommend talking to owners of 4x4s with that mod before you buy, and not just the counter guy trying to sell it to you.

Most lift kits for IFS trucks have supports that run from the drop cradle back to the transfer-case/transmission crossmember. This is because when the differential crossmember is dropped it is very hard to keep the lower A-arms from being forced backwards during off-roading. As much as we don't like these low-hanging links, we would be wary of a kit that did not use them. Also none of GM's IFS 4x4s have independent rear suspension, but rather leaf springs or coils. Note that we would rather see a new coil, leaf pack, or add-a-leaf than a lift block. Though lift blocks work OK, they do allow more leverage on leaf springs and if the pack is soft like on a minitruck or 1/2-ton they can cause spring wrap, especially if the truck has big engine power.

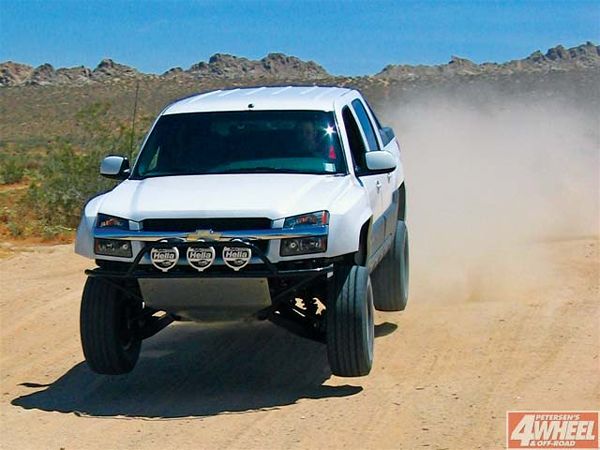

Our lead photo is an example of a custom long-travel GM independent suspension under a 4x4 Chevy Avalanche. The owner of this white prerunner couldn't find an aftermarket suspension that would hold up to the abuse of high-speed desert jaunts and eventually took his truck to Baker Motorsports, where custom upper and lower A-arms were built 3 inches wider than stock out of 4340 chromoly. This gave the axles a larger arc while keeping the CVs within their happy flex range, but did require custom Superior axleshafts made to go between the CVs. This type of suspension is not cheap, and not available in kit form, but with proper time invested in shock valving you can bomb over whoops and jumps like your favorite trophy-truck driver.

Solid-Axle Swaps

We would be remiss to discuss lifting late-model 4x4 Chevys without discussing the solid-axle swap. It's pretty obvious that we are fonder of the solid-axle suspension than an independent suspension here at 4-Wheel & Off-Road, but it's not always obvious why. The number one reason is strength; an old Dana 60 solid axle from an 1980s Chevy 1-ton will take the abuse of larger tires off road much better than a stock or lifted independent suspension. Here is why: First, when you are at maximum droop with a solid axle, the axleshafts are still straight as long as the wheels are not turned, whereas in the IFS the CVs are getting close to their maximum angle and the more angle they get the weaker they get. Second, when doing twisty trails that require a lot of articulation, the solid axle will raise the differential with the tires, and get more articulation than the IFS. And finally, when running almost any lift over 6-inch, the geometry and strain on an IFS is so far from the factory standards that we would not recommend it for severe off-road use, and we wouldn't recommend more than 8 inches of IFS lift even if you are only doing street driving. Though we like a solid axle, there are things to consider before you go to this swap. None of the GM IFS frames were originally designed for a solid-axle suspension up front. In order to install a solid axle, you will not only need the bracket for either leaf or coil springs, but also the proper crossmembers. Otherwise you risk killing the engine mounts, because the engine will be acting like the crossmember, and in turn damage other parts in the drivetrain. So if you are going to a solid axle be sure to get a kit or fabrication shop that understands this need, especially if you plan on doing serious wheeling and not just street driving. We currently know of only two companies offering a GM solid-axle swap kit - Off Road Unlimited and Fabworx. However, there are many fabrication shops that are attempting such swaps with various degrees of success. Again inspect prior work of the shop, testdrive finished vehicles if possible, and plan on paying at least as much as a complete IFS suspension.