We all know, or if you’re a newbie you have at least heard, that lowering the air pressure in your tires can help improve traction on dirt, sand, and even rocks. However, it’s a concept that not everyone understands. Why does it aid traction when off-road? How does it all work? We set out to explain and graphically represent the how and why of something many of us have long accepted but may have not fully understood.

There are upsides and downsides to almost everything, and lowering tire pressure is not excluded from this axiom. Lowering the air pressure (pounds per square inch, or psi) in your tires is only recommended for off-road travel. When tires are filled to their maximum cold pressure, only then do they attain their maximum load-carrying capacity for highway use. When you lower the pressure, you are also lowering load capacity. Dropping from 35 to 20 psi can cut the load capacity by as much as 500 pounds.

At maximum inflation pressure a tire has a mild bulge in the sidewall. That bulge becomes larger as the air pressure is dropped for off-road use, exposing the sidewall to hazards such as sharp rocks and sticks. The sidewall also flexes more at lower pressures as the tire rotates, and that flexing creates heat. This increased heat is not a problem when driving slowly off-road, but increased flexing and the associated heat at highway speeds is one of the reasons under-inflated tires fail on the highway.

Once back on the highway after an off-road adventure, you should always air up your tires (still warm from a day’s drive) to a few notches below the cold pressure maximum. You don’t want to exceed the tire’s maximum pressure rating, as over-inflation can also lead to failure.

Lowering the inflation level for off-road use can also make tires easier to roll or spin off the wheel. How low can you go without encountering a problem? That can depend upon the tire and the wheel, but in general, we have found that beadlock wheels are a good idea with most tires to avoid the tire bead/wheel rim separation blues if you run pressures of 10 psi or lower.

So how and why does lowering air pressure help traction off-road? We used a fairly common tire size and a well-known brand. From its maximum cold inflation pressure of 35 pounds per square inch (psi) to 10 psi in steps of 5 psi, we created footprints (using black paint) on sheets of rigid plastic of a BFGoodrich 33x12.50R15LT tire. The tire was on the front driver’s corner of a ’79 Jeep Cherokee with a base weight of 4,390 pounds. Each footprint was measured (length and width). Although this isn’t perfect science, the measurements taken were used to calculate a footprint size in square inches. Then each footprint was compared visually and numerically (in psi). What we learned was interesting, to say the least.

Our test setup was simple. We used a fairly common tire size, a BFGoodrich 33x12.50R15LT All-Terrain T/A. Black paint was rolled thickly across the full width of a 12 to 14-inch length of tread. The tire was then lowered, bringing the full weight of the vehicle and the painted tire tread into contact with a sheet of white plastic atop a section of plywood.

Our test setup was simple. We used a fairly common tire size, a BFGoodrich 33x12.50R15LT All-Terrain T/A. Black paint was rolled thickly across the full width of a 12 to 14-inch length of tread. The tire was then lowered, bringing the full weight of the vehicle and the painted tire tread into contact with a sheet of white plastic atop a section of plywood.

A key to accurate monitoring of tire inflation pressure is a high-quality pressure gauge. Get one. That pen-style gauge with the numbered plastic stick isn’t a whole lot better than the highly inaccurate gauges in the gas station air hoses.

A key to accurate monitoring of tire inflation pressure is a high-quality pressure gauge. Get one. That pen-style gauge with the numbered plastic stick isn’t a whole lot better than the highly inaccurate gauges in the gas station air hoses.

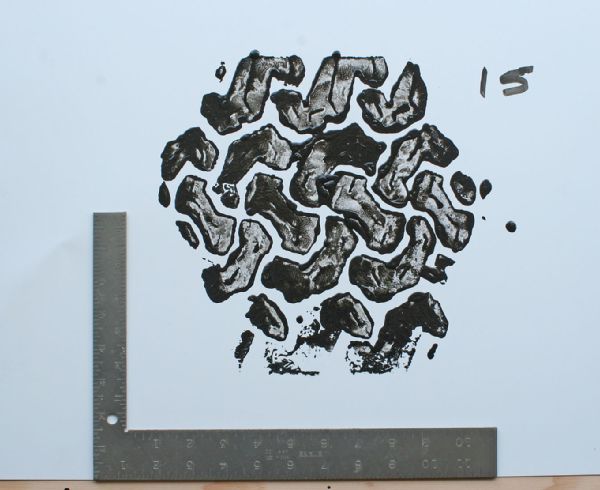

One thing that became obvious at 15 psi was the tire’s sidewall bulge. It had grown dramatically, even from a 20-psi inflation level. The sidewall bulge never touched the ground (even at 10 psi), but at such a low inflation level, the sidewall became much more vulnerable to sharp rocks and sticks.

One thing that became obvious at 15 psi was the tire’s sidewall bulge. It had grown dramatically, even from a 20-psi inflation level. The sidewall bulge never touched the ground (even at 10 psi), but at such a low inflation level, the sidewall became much more vulnerable to sharp rocks and sticks.

We began our testing at 35 psi. The tread contact patch measured just 7 by 8 1/2 inches. That’s only a tiny bit of contact, but we figure that rests 18.45 pounds of pressure per square inch on the sand or whatever you’re driving on. There’s also almost no deflection in the tread at this pressure, which means it’s not going to wrap around rocks and help you crawl very well.

We began our testing at 35 psi. The tread contact patch measured just 7 by 8 1/2 inches. That’s only a tiny bit of contact, but we figure that rests 18.45 pounds of pressure per square inch on the sand or whatever you’re driving on. There’s also almost no deflection in the tread at this pressure, which means it’s not going to wrap around rocks and help you crawl very well.

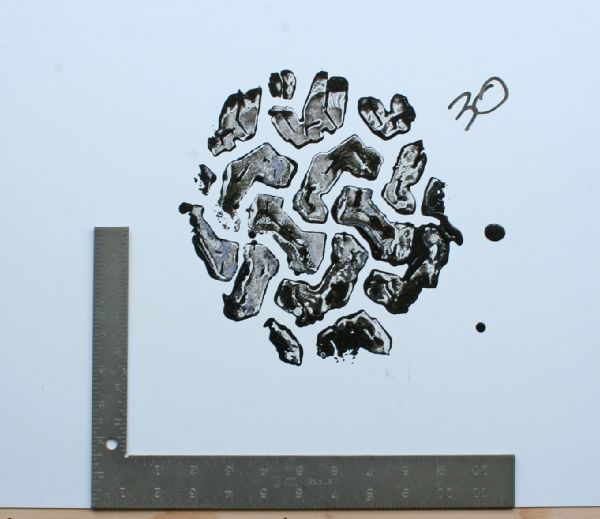

Pattern Number Two was made at 30 psi. The contact patch grew by just a 1/2-inch in length—not a lot of help for off-road flotation or tread flexibility.

Pattern Number Two was made at 30 psi. The contact patch grew by just a 1/2-inch in length—not a lot of help for off-road flotation or tread flexibility.

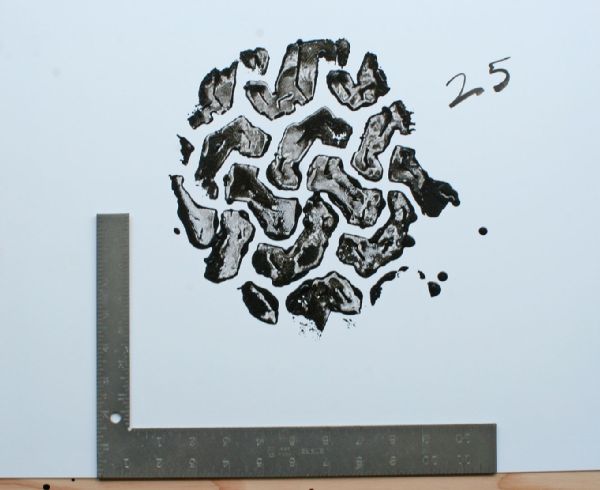

It took a drop of 10 psi to see any real gain in tread contact patch width. At 25 psi the contact patch was 8 by 9 inches, but we still didn’t see a great deal of tread flexibility yet.

It took a drop of 10 psi to see any real gain in tread contact patch width. At 25 psi the contact patch was 8 by 9 inches, but we still didn’t see a great deal of tread flexibility yet.

With 20 psi of air in the tire, we saw 2 inches of length (9 inches) and more than an inch in width (9 3/4) gained in the tire’s tread patch from 35 psi. Now we began to notice a good deal of tread flexibility that would begin to enable flotation and rock wrapping capabilities in the tire.

With 20 psi of air in the tire, we saw 2 inches of length (9 inches) and more than an inch in width (9 3/4) gained in the tire’s tread patch from 35 psi. Now we began to notice a good deal of tread flexibility that would begin to enable flotation and rock wrapping capabilities in the tire.

We went further down to 15 psi for the next footprint and didn’t see an appreciable gain from 20 psi in contact patch (9 1/2 inch length and 9.75 width), but the flexibility of the tire was much improved over its cold inflation maximum of 35 psi.

We went further down to 15 psi for the next footprint and didn’t see an appreciable gain from 20 psi in contact patch (9 1/2 inch length and 9.75 width), but the flexibility of the tire was much improved over its cold inflation maximum of 35 psi.

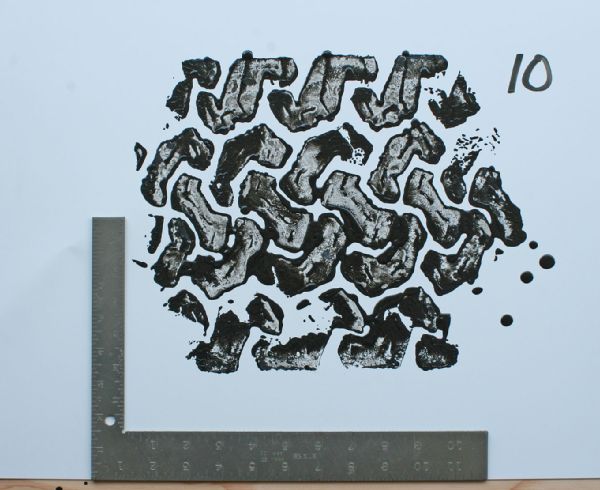

The lowest inflation level we examined was 10 psi. It was at this level the tread contact patch grew to 11 1/2 inches long and 10 inches wide. We used 1,097 1/2 pounds (a quarter of the 4,390-pound base weight of the Jeep SJ Cherokee) to calculate that, at 10 psi, there was 9.54 pounds per square inch of weight placed upon the ground.

The lowest inflation level we examined was 10 psi. It was at this level the tread contact patch grew to 11 1/2 inches long and 10 inches wide. We used 1,097 1/2 pounds (a quarter of the 4,390-pound base weight of the Jeep SJ Cherokee) to calculate that, at 10 psi, there was 9.54 pounds per square inch of weight placed upon the ground.

The dramatic difference seen here between the contact patches of the tire at 10 psi (left) and 35 psi (right) graphically illustrates just how much inflation levels can improve the traction capability of a tire. Not only is the weight per square inch half of what it was at 35 psi (offering greater flotation on sand), but the hugely increased size of the contact patch also offers improved traction and flexibility on rocky surfaces.

The dramatic difference seen here between the contact patches of the tire at 10 psi (left) and 35 psi (right) graphically illustrates just how much inflation levels can improve the traction capability of a tire. Not only is the weight per square inch half of what it was at 35 psi (offering greater flotation on sand), but the hugely increased size of the contact patch also offers improved traction and flexibility on rocky surfaces.