You could argue that traction is easily as important as ground clearance and suspension travel when it comes to dealing with tough terrain. In this situation, traction alone would be the limiting factor. Without locking diffs, this kind of crawling would be impossible.

You could argue that traction is easily as important as ground clearance and suspension travel when it comes to dealing with tough terrain. In this situation, traction alone would be the limiting factor. Without locking diffs, this kind of crawling would be impossible.

You've already heard why four-wheeling without locking diffs is really two-wheeling, or in some cases, one-wheeling. The question is, what to do about it.

The answers depend on what you drive, how much you want to spend, and what kind of driving you do. Generally, the more you four-wheel, the more you need a traction-adding differential (TAD).

The type of four-wheeling you do determines the type of TAD you want. Almost every traction-adding differential has some kind of weakness, limitation, or downside, which might include cost of installation, reliability, handling characteristics, torque-biasing capability, or noise generation.

There are lockers, limited slips and spools to choose from.

When we use the term "locker," we mean a device that actually locks up the differential so that both tires turn equally when power is applied. These may be selectable lockers, or automatic lockers.

Selectable lockers include the ARB Air Locker, cable-operated lockers, and several types of electromagnetic lockers that can be actuated via switch. They all require the operator to decide when to lock the differential and when to unlock it, so the installation will include the need to wire up a switch or other shift mechanism on the dash. They have the advantage of being completely transparent when not in operation--driven in the unlocked mode, there is no effect on steering or handling. So selectable lockers can be used in the front differential of a 4x4 without creating a handling/safety issue. Selectable lockers actually lock up the differential to split torque evenly--usually by means of pinion gears--so they offer the performance of a true locker. And because these lockers remain unlocked most of the time, rather than continually locking and unlocking on their own, they do not add wear to driveline components.

Automatic lockers are those that lock and unlock in response to changing conditions. They default to a 50/50 torque split but are designed to unlock through corners, permitting the tires to go around a corner without scuffing, and then lock again when a torque differential occurs between wheels. The advantages of automatic lockers include the fact that no driver input is necessary, so there is no need for a switch on the dash. The disadvantages are that automatic lockers can be noisy, harsh, and they can impart unwanted handling characteristics in complicated traction settings.

When we use the term "limited-slip," we are referring to those traction-adders that bias torque away from a spinning wheel toward a wheel with traction by progressively binding up the differential between them. This may be achieved by use of clutch packs, sliding cone engagement, or gear arrangements. The advantages of a limited-slip are that they are relatively driver-friendly, without the noise and harsh engagement characteristics of a true locker, and are therefore more versatile in their application. Some can transfer more torque than others, but all have their limits. Whatever the case, a limited slip provides less traction than a true locker, but much more than an open differential.

A spool, which replaces the differential, is sometimes mentioned as an option to a locking differential. A spool functionally locks both wheels together so that they must always turn at the same speed. There is zero wheel speed differentiation when going around a corner, so the inside wheel will chirp and scuff, and hopping may occur; on pavement, the axleshafts could absorb a lot of twisting. However, spools are cheap and strong. As long as the vehicle in question never needs to go around a corner, or it is always used on loose soils, a spool could be an option. For anything other than a mud bogger or sand dragster, we would say there are better options.

A word about reliability and durability: Most lockers are stronger than the parts around them, so concerns about a properly-installed locking unit itself breaking are usually misplaced. Some tend to wear more rapidly than others, but most carry warranties of a year or more. The real risk is that in an irresistible-force-versus-immovable-object situation, lockers can transmit enough force to permit twisting up a driveshaft, crunching pinion gears, or tearing the splined end off an axle. As a rule, when big engines, torque-multiplying transfer cases and tall tires combine, it's rarely the locker that crumbles.

Following is a quick review of the types of lockers out there and their potentially ideal applications.

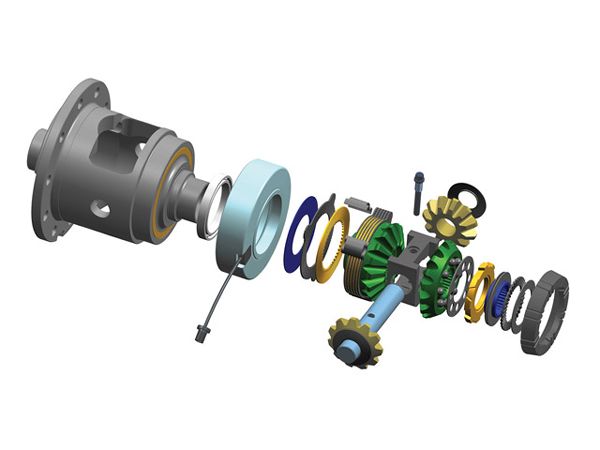

One of the best-known lockers worldwide is the ARB Air Locker. It's a true locking differential that the driver actuates. The rest of the time, the differential functions as an open differential, making the ARB suitable for use in front and/or rear axles. This particular unit is for a GM 14-bolt axle.

One of the best-known lockers worldwide is the ARB Air Locker. It's a true locking differential that the driver actuates. The rest of the time, the differential functions as an open differential, making the ARB suitable for use in front and/or rear axles. This particular unit is for a GM 14-bolt axle.

Selectable Lockers

ARB Air Locker: ARB has been offering air-actuated lockers since the mid-1980s, and the company has at least two patents on the product. The design has proven to be reliable over the years, and has been tested in high temperatures, low temperatures, against high wheel inertia, and in the field against dust, dirt, and hard overall use. There are applications for almost every 4x4, and UTVs as well. They are manufactured by ARB in Australia and are currently in use in over 80 countries throughout the world.

High-performance competition models are available for use with high-traction tires, hardened axles, and intensive torque loading. Used in drag racing, rockcrawling, and tread-type snow machines, these units employ more exotic materials to assure that they will be stronger than the axles they turn.

The ARB locker does require an air source to operate the locking mechanism. This can be a huge advantage, and in some cases, a disadvantage. By adding a compressor, the ARB mechanism assures an air supply--something every well-engineered 4x4 should have. The compressor also adds cost, but again, it's a cost that would be part of the buildup of a proper off-road-trail-going 4x4. The downside is that because the ARB is air-dependent, should an air line be torn away, or a coupling leak, then the locker will not work. These events are not unheard of in the context of intense four-wheeling, so it makes sense to carry an air line repair kit in the toolbox, just in case. ARB offers a variety of compressors to go with the Air Locker, with a range of price points.

From a performance point of view, the ARB is a true locker that, like other selectable lockers, does not affect handling or create driveline wear when not engaged. That makes it suitable for use in the front differential, as well as the rear. Hardcore rockcrawlers we know like it in the front, because they can actuate it in a particularly difficult spot, gain traction, then click out of it after moving forward just a few feet to regain easy steering control.

Installation time and complexity vary widely, depending on the vehicle. A well-organized professional mechanic might be able to install an ARB in the front Dana 30 of a Jeep in three hours. The same guy might need the better part of a day to do the job on an IFS Toyota front axle. Nils, a tech at ARB, estimated that installation compares to those of other selectable lockers: "The only thing that would add time is you've got the air delivery system, which takes a little more caution, and you would be drilling and tapping for the air line." Tools for the job would include a dial indicator, a micrometer to measure shims to get the backlash right, and a case spreader is a good idea with any locker install. Nils says the install is "definitely feasible for the average mechanic in the home garage," but the amount of time "will depend on how organized your toolbox is."

Another switchable locker is the Eaton ELocker. This unit is for the Dana 30 front axle, and has seen a sharp rise in popularity among weekend-warrior Jeepers now that 30-spline axle shafts are available. After a long period of development, Eaton has gone to a four-pinion design for strength and reliability.

Another switchable locker is the Eaton ELocker. This unit is for the Dana 30 front axle, and has seen a sharp rise in popularity among weekend-warrior Jeepers now that 30-spline axle shafts are available. After a long period of development, Eaton has gone to a four-pinion design for strength and reliability.

Eaton ELocker: The electronic ELocker is a selectable locker that has been a long time coming as an aftermarket product. "They were originally developed in 1999 for AM General on the OE side of our business," said Eaton engineer Jeff Saxton, "as a pin-style device where there is a series of pins that pin one of the side gears to the case. It gives you a very simple and very durable unit. Then as we started to broaden the product line into smaller axles, we saw that you could not just scale down that type of design into the smaller axle cases and maintain the same level of durability."

That meant that Eaton had to develop a new electronically locking product for smaller axles, which is now called the "collar-style" ELocker. "Instead of using pins that drive through the flange of the case, we use these locked rings that are actually internal to the case. That allowed us to make the whole package smaller and maintain the type of durability we were looking for."

The newest applications, for the Dana 30 and 35 axles with both 27- and 30-spline axleshafts, were some of the hardest to engineer. "We originally attempted to do a two-pinion design, and simply could not get equivalent durability out of it. So we had to take a step back and ultimately go to a four-pinion design. That meant we had to extend our development time, but we felt that would be better than compromising the product."

According to Saxton, the move to a four-pinion, collar-style electronic locker has made a huge difference in strength and reliability. "Our ELockers are the most bulletproof out there," he told us. "I would not go so far to say it is as strong as a Detroit Locker. You're still looking at a traditional differential design with pinion shaft and pinion gears. Whereas a Detroit distributes the same load on far, far greater surface areas. But the flip side of that is the selectability. We developed the Elocker to give the driver selectability in its use."

The ELocker delivers the torque-biasing performance of a true locking differential. As long as the wheels are turning at the same rate (within 50 rpm) it can be actuated at speeds of 20 mph and below; otherwise, the maximum engagement speed would be about 5 mph. The ELocker can be used when operating in 2-Hi, 4-Hi or 4-Lo. Because it returns the differential to an open state when deactivated, it is suitable for use in front, rear, or both axles. The ELocker is maintenance free, requiring no special lubrication additives, and it is compatible with ABS and vehicle stability control systems on newer 4x4s. Unlike the ARB Air Locker, there is no air supply requirement, but you do have to wire the locker to a switch. The assembly kit includes the switch and wiring.

The Auburn ECTED is another true locker that actuates by electromagnetic switching, though the internals are a bit different. Auburn sources advise that the ECTED also incorporates clutch packs that can act as a sort of limited-slip when the differential is not locked up.

The Auburn ECTED is another true locker that actuates by electromagnetic switching, though the internals are a bit different. Auburn sources advise that the ECTED also incorporates clutch packs that can act as a sort of limited-slip when the differential is not locked up.

Auburn ECTED: Auburn Gear produces a full line of differentials for Chrysler, Ford, GM, and Toyota vehicles, all compatible with ABS and OEM electronic control systems. The company has been in business for nearly 50 years in Auburn, Indiana. They also offer spools, mini- spools and a wide variety of service kits. Ralph Traycoff at Auburn Gear told us that the ECTED is typically purchased by off-road enthusiasts looking for true locking differential performance. "I think the best setup depends on what you're using it for," Traycoff told us. "If you're towing a boat, maybe a limited slip is best. For a serious Jeep, it's the ECTED. For drag racing, you want a spool."

According to the company website, the Auburn ECTED locking differential is a selectable unit that can operate as a limited slip when not engaged. When it is engaged, it becomes a full-locking differential. Although it uses a dash-mounted switch to actuate as a locker like the ELocker, the internal design is different. Inside, there is a clutch pack that provides the limited-slip mode. As torque increases, the clutch pack is compressed and the differential begins to bias torque to the high-traction wheel. To get true locking performance, the driver actuates a switch that electrically causes a ball-and-ramp arrangement to engage a center pin that ultimately compresses the clutch pack and gives the user a solid axle assembly. There are no shift forks or pins that have to line up to move into the locker mode; Auburn sources say it can be switched on or off at most any speed. Like other selectable locking differentials, it is quiet and can be used in front axles with or without lockout hubs, although the ECTED is not recommended for use in front axles that have an inter-axle disconnect, like the Jeep Cherokee XJ. The internal gearing is made from 9310 heat-treated billet steel. The warranty is for one year, and the unit is backed by a replacement/exchange program.

OX Locker: This is a selectable locker that can be actuated by any of three modes--cable, air pressure, or a switch that activates a remote-mounted electrical actuator via a short cable. The actuation occurs when the cable moves a fork mounted in the OX differential cover. The fork actuates a locking ring that moves into a locking side gear. "It's actually the same concept as an ARB," according to Chip Keckler at OX Lockers. The internals (carrier case, forks, and rings) are heat-treated for durability and all are made in the USA. The side gear is not straight-cut, but back-cut, so it looks like a dovetail joint when engaged, making an extremely positive connection. "We probably have the strongest selectable locker on the market," Keckler said. The flip side of that is you have to unload the system to get back into open mode, either by taking your foot off the accelerator or otherwise unloading the system from torque.

Installation is going to be about the same as any other locker, except that routing and adjusting the cable takes some thought, as it should not be exposed to heat or abrasion. When actuated using an air line, any 100psi source of air pressure can be used.

Inside a Detroit Locker there are no pinion gears, so the Detroit can distribute forces over a wider, stronger surface area than most lockers, and the carrier is built to last. The Detroit is known to be extremely strong, but a little rough in transition, so they are generally not advisable for use in daily-driven vehicles that might see slippery surfaces. On really tough trails, the Detroit lives up to its reputation.

Inside a Detroit Locker there are no pinion gears, so the Detroit can distribute forces over a wider, stronger surface area than most lockers, and the carrier is built to last. The Detroit is known to be extremely strong, but a little rough in transition, so they are generally not advisable for use in daily-driven vehicles that might see slippery surfaces. On really tough trails, the Detroit lives up to its reputation.

Automatic Lockers

Detroit Locker: The Eaton Detroit Locker is doubtless the best-known true locking differential in the four wheeling arena. It is probably no exaggeration to describe the Detroit as legendary for durability and for its ability to maintain a 50/50 torque split. When the vehicle encounters a corner, the Detroit unlocks automatically via a speed-sensitive mechanical mechanism, permitting the tires to track around the corner at different speeds. Once you are going straight again, it automatically re-engages without driver input.

Even with those good qualities and others included, a Detroit Locker is not always going to be the best traction-adder for the job.

"There are reasons why you might not choose a Detroit," Eaton engineer Saxton told us, "one in terms of performance, two in terms of customer satisfaction. Everybody is familiar with the type of feedback that you get from a Detroit when it reengages, and the sound that you perceive. That alone is why that product can never be considered by an OEM for an application these days. Beyond that, any vehicle that is going to operate on high-mu conditions for the majority of the time, we typically would not recommend it. On a slippery surface--rain- or snow-covered-- you're going to have a tendency to slide that rear end on a low-traction surface."

Most of us know fellow four wheelers who have experience with using a Detroit in both axles, and even some who say it's fine once you get used to it. That may be, but the people at Eaton are uncomfortable with the idea of a Detroit Locker, front or rear, in a daily driver in bad weather, especially in a short-wheelbase vehicle. "We do consider it to be a specialty device for specialty applications. It's been the standard now for circle track, drag racing, off-roading, and so on. But the real key is not to use it as a device on a daily driver on a high-mu surface," Saxton said.

The portfolio of applications for Detroit Lockers is broad and complete. They are available, pretty much, for every axle commonly used in vehicles that might ever go off-highway.

There are a number of true lockers available that offer easy installation, lower price, and good performance. These "DIY lockers" have been sold under a number of brand names, but all have certain things in common: They replace the side and spider gears, retaining the original case, so they can be installed in a matter of hours by the backyard mechanic. While they are subject to the same handling concerns as any other automatic locker, they offer solid traction for less cost, and are generally considered to be a good deal on a weekend-warrior-type 4x4 as long as tire size remains reasonable.

There are a number of true lockers available that offer easy installation, lower price, and good performance. These "DIY lockers" have been sold under a number of brand names, but all have certain things in common: They replace the side and spider gears, retaining the original case, so they can be installed in a matter of hours by the backyard mechanic. While they are subject to the same handling concerns as any other automatic locker, they offer solid traction for less cost, and are generally considered to be a good deal on a weekend-warrior-type 4x4 as long as tire size remains reasonable.

"DIY" Lockers

A growing number of drop-in automatic-locking lockers are offered under a variety of brand names. These are true lockers that replace the side and spider gears, using the original case. They offer good performance for less cost, and the key advantage of being fairly easy to install for the average backyard mechanic. Some of the units on the market include the Lock-Right (Richmond Gear), the Quik-Lok (Genuine Gear), and the Aussie Locker (Torquemasters Technology). Eaton discontinued their version of the DIY locker, the EZ Locker, about a year ago, and it is no longer available.

There is no question that installation is far simpler than a locker that requires setting up the gears after the locking device goes in. John Bolton at Richmond Gear told us that the installation could take "a couple of hours in a standard open carrier." Cost is also an attractive factor in favor of these types of lockers, partly because the installation takes less time, and partly because "you're not buying the whole carrier," as Bolton put it.

These lockers all deliver a 50/50 torque split, so from a vehicle dynamics point of view, there would be the same concerns as a Detroit Locker on low-friction surfaces.

Realistically, their potential for reliability is based on the strength of the carrier they are installed in. In a good, strong carrier, these types of lockers should be highly reliable, but there may be applications where the carrier limits strength, and when large tires are combined with hard off-road use, there may be wear that leads to failure. Complaints of clicking noises or hard locking may be related to the fact that the stock cross-shaft, which is usually reused, can wear. The venerable Positraction, known since the muscle-car era of the 60s, is still on the market but in a much-improved form. By adding space-age materials to the clutch pack, this limited-slip diff is no longer so much prone to wear. By adding stronger or weaker springs, the Posi can be "tuned" to the user's preference.

Limited-Slip Diffs

Eaton Posi: In the 1960s, Positraction was an available feature in GM muscle cars and other sporty offerings. The design involved clutch packs and springs that worked to engage the axles when one wheel started to spin. Positraction worked for awhile, but if you drove hard on it, the clutches wore out and it had to be rebuilt. These days, the design is the same but the pieces are much tougher.

"The wear factor--I can't say it's been eliminated, but very nearly so," says Eaton engineer Saxton. "Those original Posis were very simple steel-plate-on-steel-plate types of clutch systems. You had a combination of things happening. One, the plates wore and became thinner, so the ability of the unit to generate bias slowly diminished because the plates didn't press as effectively against each other as when new. The plates themselves, the constant sliding actually polished them, so the frictional characteristics of the plates changed. The combination of the two, over time and depending on use, could easily wear out an early Positraction unit. "

There have been a lot of changes with materials used in modern day Posis, even though the principles remain the same. One of the key characteristics of the current units is the use of an aerospace material called pyrolitic carbon. Originally developed for brake linings on airliners, the material is still in use today. This material is highly resistant to wear, which eliminates that decay over time. "What small amount does go smooth will not develop into a frictional characteristic change," Saxton told us. "The clutch plates don't change throughout their life, so the current product as a daily driver/recreational vehicle type of thing, we would go so far as to say they retain their performance for the life of the vehicle; it's that good."

By adding springs that might be lower or higher in strength, the action of the mechanism can be "tuned" for harder use. "In the case of a professional racer or other extreme levels of use, they are certainly rebuildable. In the case of anything short of a racer running every weekend, for most consumers, general-purpose use, it's pretty rare that we would ever see one that would require rebuilding anymore," Saxton said.

Eaton continues to manufacture the Positraction limited-slip because the name is well established, everyone knows how it works, the cost is reasonable, and there is a traditional following for the product. To the four wheeler, it's the kind of TAD you don't use for your rockcrawler, but you might want a posi in the rear axle of your tow rig in case of rain, bad weather, a muddy section of road, or on a slick boat ramp.

Auburn Limited-Slip: When people refer to the "cone type" limited slip, the Auburn limited-slip is what they are talking about. Instead of using clutch packs to transfer torque, the Auburn limited-slip uses cone-shaped pieces that resemble an ice cream cone with the pointed end cut off. As the cones are seated into the differential case, they transmit torque through side gears to the axleshafts, overcoming springs that hold them apart. When torque demand is reduced, as in going around corners, the cones separate from their seats in the differential case, freeing up the side gears and allowing the axleshafts to rotate independently. The design is intended to maximize the amount of torque transfer, and the speed of torque biasing, without compromising the everyday driveability of the vehicle. The Auburn limited-slip comes in Pro Series and High Performance Series versions, which are well suited for drag-racers and muscle car owners who want especially quick, positive lockup upon hard acceleration. Another application would be in the rear axle of a tow vehicle that sees occasional use on a boat ramp or other low-traction surface.

The Truetrac is a gear-type limited slip that uses helical gears to bias torque. This has always been considered an exceptionally long-wearing limited-slip design. Eaton acquired the Truetrac when the company bought Tractech in 2005, quickly resumed production, and now markets the unit as the Eaton Detroit Truetrac.

On dedicated 4x4s, prior to the advent of selectable lockers, the Truetrac was considered strong and effective enough to live in the front differential of a rockcrawling rig. Even today, with other options available for the active four-wheeler, it could certainly be a practical upgrade in that situation versus an open front diff. However, on a daily-driven 4x4 or a tow rig that sees slippery surfaces, the Truetrac is at its best working as a smooth, quiet, and effective limited-slip unit.

It's described by Eaton engineer Saxton as "one of the most serviceable products we've got, because of its versatility. It's got incredible durability. In the case of a 4x4 that sees a lot of off-roading but still has to be a daily driver, you can get excellent response under very, very difficult conditions. Yet the second you hit that hard road surface again, it allows the vehicle to be driven. The nice thing is you can even drop it into a front axle and get the performance benefits." The ability of the Truetrac as a torque-sensing mechanism is part of its appeal. Still, the Truetrac is a limited slip, not a locker. "There is a limit as to just how much bias it can generate."

Eaton specifications indicate the Truetrac can transfer up to 3.5 times more torque to a high-traction wheel--no small amount, but still less than a true locking differential. In other words, for a rockcrawling 4x4 that is rarely street-driven, the Detroit is a better choice for the rear axle. For the daily driver, the Truetrac fills the bill. And for the tow rig, a Truetrac in the rear axle provides good grip for those moments when traction is at a premium. There are two-pinion, three-pinion and four-pinion gear designs, with the greater number of pinion gears being used to distribute higher loads in bigger axles. The Truetrac is available for most Chrysler, Dana, Ford, and GM axles, and is original equipment in the Ford F-450/550 and GM C-series trucks.

This device, developed on an OEM basis by Eaton under the name EGerodisc, is a hydraulically operated, electronically controlled limited-slip that provides an optimal stability/traction solution at any speed. The next generation of this type of differential will have "torque vectoring" capability.

This device, developed on an OEM basis by Eaton under the name EGerodisc, is a hydraulically operated, electronically controlled limited-slip that provides an optimal stability/traction solution at any speed. The next generation of this type of differential will have "torque vectoring" capability.

Will Traction Control Make Lockers Obsolete?

On the newest 4x4s, especially SUVs, traction control is enhanced electronically, in some cases so well it might appear that adding another locking differential device would be unnecessary. These electronic traction control (ETC) systems work by applying braking control to a spinning wheel, thus transferring power to the wheel that has the most traction. Should a wheel lift while crossing a tree root, or a slick spot appear on a road or trail, these systems work automatically to keep the family SUV moving. ETC systems are popular because they're essentially free technology. Once you have four-channel ABS, you can add ETC at very little cost. So the question becomes, given the superb, seamless capability of the brake-based traction control system: Does anyone really need a traction-adding differential any more?

"It's fairly easy to demonstrate the limitations of any brake-based traction system if you challenge the vehicle enough," Eaton's Jeff Saxton said. "The problem is on those vehicles, if they're just using standard open differentials, there's nothing for the e-brakes to work against. ABS can apply brake to a spinning wheel, but that doesn't necessarily create enough torque across the axle to try and drive torque across to the other wheel that might have better traction. So while the braking can be effective for fairly moderate situations, the minute you start talking about off-road capabilities, it's pretty easy to demonstrate the limitations of brake-based systems."

As a rule, factory ETC systems can't take prolonged demand in a challenging situation, such as 100 yards of mud or a long, snowy driveway, without building up heat. "Most of those systems, if you tax it for more than a minute of time, it will go into a fail-safe mode and shut itself off."

That's the reason why manufacturers of SUVs that are intended to handle actual off-highway use, such as Jeep, Toyota, Land Rover, Hummer, and others, often add selectable electronic locking differentials to their 4x4s along with their traction control system. When the ETC gets overtaxed, the manual locking differential can still provide traction without heating up the brakes, and generally better torque transfer. Where no OEM equipment is present, an aftermarket device can be installed to provide the same function.

Another future technology, electronic stability control (ESC), is also complicating the future of locking differentials. When ESC becomes standard equipment in 2011, there is no guarantee enthusiasts will be able to slap in a mechanical locker without compromising a government-mandated safety system. Ironically, the advent of ESC has meant that the companies with OEM clients, like Eaton, will have opportunities to develop new business.

"Stability control is one of those areas of the industry that is as much of a challenge in terms of consumer education as it is in technology. If you really dig into that, you find out that a brake-based system is limited at the very best in terms of what it brings to enhance safety in a reactive system. If we're talking milliseconds, that may not be an adequate response. In terms of where the industry is going, there is the whole technology of torque vectoring--where you actually apply engine power as opposed to brake, to drive the vehicle into the intended path to try and mitigate an out-of-control situation. It takes a very special, fast-acting type of differential. We have a product we market under the name EGerodisc that can be modulated quickly enough to actually generate a combination of additions on both axles and transfer case to drive the vehicle in an intended path. I think you're going to see a lot more of that in the next few years. In the military, there is a huge awareness of torque-vectoring technology. It's incredible stuff, even to those of us who play with it every day. "