Qualifying up front is very important for several reasons. The foremost is to avoid early trouble as the cars farther back make their moves to the front. Overaggressive driving is usually observed very early in the race, and you don't want to be in the middle of, or behind, that process.

Too many drivers that are otherwise successful are terrible qualifiers. Why, when in practice and in the race they can run comparatively fast laps, do they fall down when it counts the most? We have not only discovered a better method for qualifying, we have also discovered and will explain to you why it works

We decided to conduct a test session and somewhat of a school and asked our friends, Mike and Kristal Loescher, to instruct a team whose qualifying often leaves something on the table. At the time, Zehr drove our NASCAR Late Model stock car and other project cars for several years.

Mike Loescher explains the error of his ways to Dalton Zehr after a simulated qualifying run. The problems with his approach were evident and he began to immediately make changes in subsequent runs. It involved overdriving the entry which slowed the late entry and middle portion of the track. Once corrected, the result was very impressive.

Mike Loescher explains the error of his ways to Dalton Zehr after a simulated qualifying run. The problems with his approach were evident and he began to immediately make changes in subsequent runs. It involved overdriving the entry which slowed the late entry and middle portion of the track. Once corrected, the result was very impressive.

Our instructor was BJ McLeod, a Florida Super Late Model champion who spent time with Zehr for this test. McLeod has a lot of wins to his credit and more importantly for this effort, a lot of fast times in qualifying. He teaches the driving method developed by Mike and Kristal that we reported on in the CT article, Head of the Class, July ’04 issue, page 81. This is where I took the three-day driving course and where we explained the correct method for driving a stock car. Much of what follows will sound familiar to those who read that article.

Zehr has won the ASA Late Model Nation Championship, the aforementioned Tundra Championship, and numerous track championships since we first did this story. The information learned here was useful to him as it will be to you. All you have to do is follow along with this process and try to understand how gains are made and time is lost by your qualifying process, be it right or wrong.

For the regular driving school, Loescher paints dots on the track surface to mark where the students lift going in, quit braking, and begin to accelerate. For our qualifying school, we referenced these points, but were able to run a little differently thanks to the technique.

For the regular driving school, Loescher paints dots on the track surface to mark where the students lift going in, quit braking, and begin to accelerate. For our qualifying school, we referenced these points, but were able to run a little differently thanks to the technique.

First, there is turn speed. If you can get through the turns at 68 mph during practice, then that speed should increase by about 2 or more mph on fresh qualifying tires. In a previous article, we found that 1 mph on a half-mile track was good for about 0.2 second, so we should pick up around 0.4 second per lap on fresh tires.

There is also the factor of more aggressive acceleration. That again plays into the fresh tires being able to grip and hold better when asked to accelerate the car earlier than it did on used tires. If we can begin accelerating sooner, then we should gain more speed over the length of the acceleration zone for maybe another 0.1-second gain per straightaway.

With new rubber on the car, we have theoretically gained 0.6 second over our practice times. A good qualifier can do this on a consistent basis, or even better. How do they do that? Let's break this fast lap down and see why it is faster.

Lifting at the right points seems early and slow, but in reality helps produce a faster average speed, which translates into a lower lap time. Lifting early does not mean slowing early, just ending the acceleration phase. Speed is relative to turn radius and usually the radius decreases towards mid turn on most tracks. So, you can carry more speed deeper into the corner by lifting early and letting the car roll gradually slowing to the point of mid turn.

Lifting at the right points seems early and slow, but in reality helps produce a faster average speed, which translates into a lower lap time. Lifting early does not mean slowing early, just ending the acceleration phase. Speed is relative to turn radius and usually the radius decreases towards mid turn on most tracks. So, you can carry more speed deeper into the corner by lifting early and letting the car roll gradually slowing to the point of mid turn.

In our test, McLeod drove Zehr around the track and instructed him on where to lift, how to brake, where to get off the brakes, and when to begin to accelerate. The best entry is when the lift point is seemingly premature and the worst entry is when the entry is delayed.

Most drivers will tell you that it feels fast to overdrive the entry. This is because it takes a lot of effort to drive the car. It is a bit exciting and dangerous, for sure, but it is not fast. Early lifting will help stabilize the car and cause it to settle sooner. Once the car is settled, it will be ready to accelerate sooner. Accelerating sooner means that our acceleration zone has lengthened. If we accelerate longer, the car will attain a higher average speed, and that is where the extra 0.1 second per straight comes from.

Backing off earlier allows us to use much less brake, and therefore, we will be faster through the normal "braking" zone. That is the area between the lifting point and the point where the car settles into its turn attitude. A lot of time can be left "on the table" in this portion of the turn.

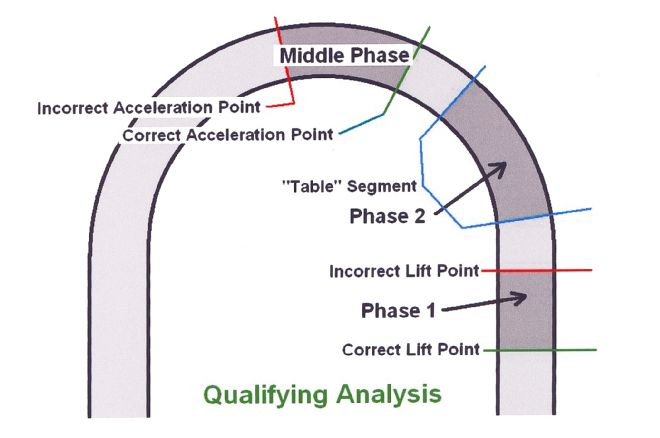

With the entry correct and the braking phase faster, the acceleration can begin sooner and the middle phase will be faster. All three of these phases will be faster, as will the entire lap.

Over running the mark by as little as a car length can cause a slowdown of a couple of tenths in lap times. At speed, you pick your lift points based on comfort and control and never deviate. It is a discipline thing and hard to master for some. But if you let the stop watch tell you what is fastest and not your feel in the car, you will progress much more quickly.

Over running the mark by as little as a car length can cause a slowdown of a couple of tenths in lap times. At speed, you pick your lift points based on comfort and control and never deviate. It is a discipline thing and hard to master for some. But if you let the stop watch tell you what is fastest and not your feel in the car, you will progress much more quickly.

First, we have to slow the car down to the allowable midturn speed in a much shorter length of time. We can only do this by applying a lot of brake. We slow the car down quickly and probably end up slower than we could have negotiated the middle due to lack of feel as excess load is transferred to the front tires.

The "table" portion we talked about is now slower than we could have driven it, the middle is slower, and the acceleration point is pushed farther around the turn as we wait for the car to settle down. We have gained a slight amount of speed in the first phase, lost some speed in the second phase, lost speed in the middle phase, and ended up accelerating late and at a lower speed. All of this adds up to a net loss of several mph and three to five tenths per turn.

This breakdown of the turn segment shows the three phases we are concerned about. The correct lift point is well before the incorrect one. This is where the fast lap starts. When going in too deep to the red line, excess braking must occur and the “table” section suffers.

This breakdown of the turn segment shows the three phases we are concerned about. The correct lift point is well before the incorrect one. This is where the fast lap starts. When going in too deep to the red line, excess braking must occur and the “table” section suffers.

During the year, our driver might have run in the 16.30's in practice and expected to turn 16.00's in qualifying. It would not be unreasonable on new tires to gain 0.3 second or more, but two things happened. The car was slower in the first qualifying lap and even slower in the second lap.

The first lap was driven hard to heat up the tires, and the second lap was a banzai lap intended to produce a fast time. It was executed by driving in way too deep, using lots of brake, and then, after a prolonged period of trying to get it settled down, accelerating late at a lower speed. He did all of the wrong things and it showed in the times.

At one race, I observed another driver's qualifying lap and would have sworn that it was very slow. It turned out to be the fastest time of the day. It looked uneventful, and that is exactly what it should have looked like. He backed off early and smoothly, rolled into the turns with little braking effort, squeezed the throttle early, and rolled off the turn without one wiggle or twitch. And it was fast.

The entry dot for lifting going into turn three at New Smyrna Speedway is well back from the deepest point that would still allow you to keep from crashing, but offers a much more stable entry and more retained speed for an overall faster lap. This is the hardest thing for a driver to understand and perform.

The entry dot for lifting going into turn three at New Smyrna Speedway is well back from the deepest point that would still allow you to keep from crashing, but offers a much more stable entry and more retained speed for an overall faster lap. This is the hardest thing for a driver to understand and perform.

He doesn't let emotion or the heat of the moment drive his car. He does exactly what should be done by lifting at the correct point, letting the car roll into the turn and settle down, and then beginning to accelerate as soon as the car is ready, which is earlier than most. The lap times tell the story, and it works.

Lifting early feels like it will be slow. It takes a lot of discipline to work against the tendency to over-run the entry. Doing what works out right on the stopwatch and against what feels right is a process that has to be learned and memorized. It has to become second nature. Once you see the results, you will know what has to be done.

Loescher goes over the theory and how it works in the different phases. The students can get a good idea of how and why this makes sense. Having an instructor define the process and then observe and correct the inevitable mistakes was invaluable.

Loescher goes over the theory and how it works in the different phases. The students can get a good idea of how and why this makes sense. Having an instructor define the process and then observe and correct the inevitable mistakes was invaluable.

Next, we ran two-lap qualifying runs in Dalton's car on cold tires. We used the same used tires as before, but waited a sufficient amount of time between runs in order to cool the tires. Remember that this was in the middle of the day on a Tuesday. There was no rubber on the track, and it was hot and greasy. The track remained consistent during the entire test.

The first run was done just the way he had always qualified and was a 19.8. On the next run, again on the same but cooled tires, and with a little instruction from Mike and BJ, the time fell to 19.50. We waited some more for the tires to cool, and then, with a few more corrections, the time dropped again to 19.30. By further fine-tuning the process, we were seeing 19.0's.

When the entry is executed correctly, the car stays on the bottom, is under control at all times, is faster in the middle, and feels comfortable to accelerating early. The distance the car is under power and gaining speed is greatly increased with this method.

When the entry is executed correctly, the car stays on the bottom, is under control at all times, is faster in the middle, and feels comfortable to accelerating early. The distance the car is under power and gaining speed is greatly increased with this method.

After the school was over and everyone had left, Dalton practiced some more (with the same tires and setup) and got the times down into the 18.80's. The first runs from 19.8 to 19.5 could have just been getting the tires scuffed and the track blown off, but the real gain was around 0.7 second. At the races, when Dalton should have been three to four tenths quicker on new tires in qualifying, he was sometimes that much slower. With the method taught by Mike and BJ, he might now be able to start up front or even get a pole or two this season.