Most times on Saturday-night tracks, a spinout like this ends harmlessly and the racer is able to continue the race. But it's the "big one" that we must always be working to protect drivers from.

Most times on Saturday-night tracks, a spinout like this ends harmlessly and the racer is able to continue the race. But it's the "big one" that we must always be working to protect drivers from.

It's unfortunate that any discussion about head-and-neck safety systems uses Dale Earnhardt's death at Daytona in 2001 as a baseline, but that's the truth. After that tragedy, NASCAR took positive-and drastic-steps to protect its drivers. As head-and-neck systems became mandatory in NASCAR's top touring series, racers began to get a much better idea of how to protect themselves. Manufacturers also learned better ways to construct the devices to further improve protection.

Unfortunately, those benefits did not immediately find their way to Saturday-night racetracks across America. Many sanctioning bodies and tracks did not require any sort of head-and-neck restraining device, and racers resisted them most often saying that they could not afford the additional cost. Many also mistakenly believed that because they weren't racing on mile-and-a-half ovals like the Cup guys that a restraint system was unnecessary. The truth is that the tighter turns found on 1/2-mile bullrings means that a nearly head-on collision with the outside retaining wall is much more likely than on a NASCAR Sprint Cup superspeedway.

Thankfully, all that is changing as drivers become better educated as to how they can protect themselves, and more options for head-and-neck restraint systems come on the market. One of the major players in this movement is Trevor Ashline, owner of Safety Solutions, which offers more SFI-38.1- approved options than any other company involved in motor racing.

Trevor Ashline (right), owner of Safety Solutions, discusses options for head-and-neck restraint systems with racer Chris Hargett. Ashline encourages racers to try to get hands-on time with different restraints before buying one. One test is to actually try to bend the restraint and see how flexible it is. If it can withstand 70g's, you shouldn't be able to bend it. "Consider the worst possible wreck," Ashline explains. "If the car flips 10 times, I want the restraint to protect you on that 10th-consecutive hit just as well as it does on the first."

Trevor Ashline (right), owner of Safety Solutions, discusses options for head-and-neck restraint systems with racer Chris Hargett. Ashline encourages racers to try to get hands-on time with different restraints before buying one. One test is to actually try to bend the restraint and see how flexible it is. If it can withstand 70g's, you shouldn't be able to bend it. "Consider the worst possible wreck," Ashline explains. "If the car flips 10 times, I want the restraint to protect you on that 10th-consecutive hit just as well as it does on the first."

When it comes to determining how to protect yourself, understanding the SFI-38.1 certification is important. It was developed specifically as a testing procedure to quantify how well head-and-neck restraint systems actually protect the driver. Originally, the first certification processes for head-and-neck restraints required that it adequately protect a driver in a 50g frontal impact. For comparison, Dale Earnhardt's crash was calculated to be approximately 42g's.

Shortly thereafter, the SFI Foundation increased its certification standards with SFI-38.1, which says that a restraint system must be capable of protecting a driver in a 70g crash. By the way, "protecting" for the SFI Foundation means the restraint must reduce the force on the driver's head to less than 4,000 newtons of tension on the neck. That may not mean much to you or me, but Ashline puts it in perspective when he says that if your neck stretches 27 millimeters in a crash, then it's probably broken. If you were to actually experience a 70g crash, there probably wouldn't be a single part left on your car that is reusable.

Although he is constantly developing and testing new systems, Ashline says that the most important part of his job is educating racers. He also says that spending time one-on-one with racers has helped him develop restraint systems that not only provide superior protection, but also are as comfortable and easy to use as possible.

We recently stopped by the shop of Dirt Late Model racer Chris Hargett, who had been contemplating purchasing a head-and-neck restraint system, so that Ashline could walk him through many of the major decisions a racer must make.

One of Ashline's most advanced head-and-neck restraints is the Hybrid. Ashline says he tries to build redundancies into his systems. For example, the Hybrid uses three load paths to hold the head in position. If, for some reason, one load path fails, there are two more to make sure the driver is protected. The Hybrid is also one of the only systems available today that is tested and proven to be just as effective in the much more common 30-degree side impacts as it is in a full frontal impact.

One of Ashline's most advanced head-and-neck restraints is the Hybrid. Ashline says he tries to build redundancies into his systems. For example, the Hybrid uses three load paths to hold the head in position. If, for some reason, one load path fails, there are two more to make sure the driver is protected. The Hybrid is also one of the only systems available today that is tested and proven to be just as effective in the much more common 30-degree side impacts as it is in a full frontal impact.

One of the most important criteria is making sure that you can get out of the car quickly with your helmet and neck restraint on if the need arises. After all, preventing a neck injury is nice, but if the restraint causes you to be trapped in your car and burned in a fire, its service as a safety device is moot.

Ashline says it is also important for any device you wear to be comfortable. A restraint system that isn't comfortable to wear means most drivers will "forget" to put it on come race day, or leave the straps loose, trying to make the device easier to wear. But if the straps are too loose, the device may provide no more protection than wearing nothing at all. If you have the opportunity to try out a device before you buy it, try putting it and your helmet on and sitting in your car for 10 to 15 minutes. If it doesn't get in your way, then you'll know you will be able to put your full focus on driving the racecar and not fidgeting with your safety systems.

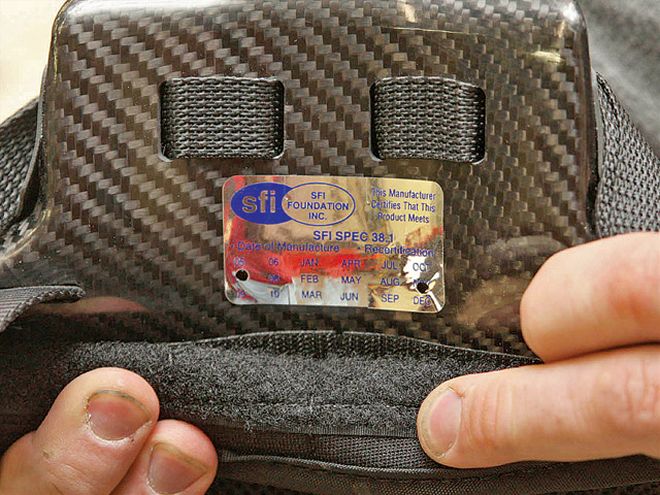

Finally, take a good hard look at the device itself. If it has SFI-38.1 certification, it will be displayed somewhere on the device with a certification sticker. The SFI-38.1 certification is currently the toughest standard on the market, and definitely what you should demand. One caveat, however, is the SFI-38.1 certification is mainly a test of how well the restraint can protect against a head-on impact.

Ask the manufacturer of any device if it has sled impact numbers for impacts on an angle to the car. For example, most hard hits are on the right-front corner of the car, and while a head-on collision with the wall can be violent, they are much more rare. Ashline says that because he spends a lot of time with circle track racers, he understands the importance of protecting against angular collisions and is one of the few companies that actually put a priority on this with sled testing.

Assuming that because you race on a short track you don't need a head-and-neck restraint is an antiquated approach to safety. Do yourself and your family a favor, there are enough head-and-neck restraints available today. Go out an find the one that's right for you.

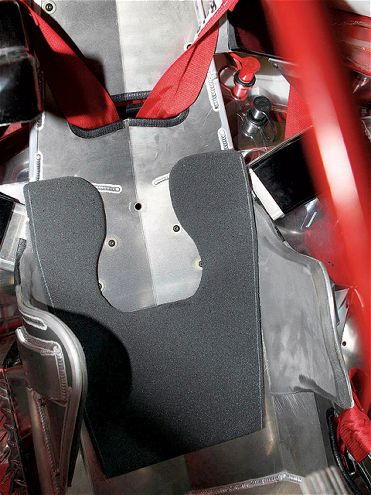

Comfort is a critical factor in the design of a restraint. If a driver isn't comfortable wearing it, he likely won't wear it correctly-or at all. Ashline uses a foam pad that sticks to the seat and keeps the "backbone" of the device from digging into the driver's back. Because it sits into the pad's cutout, it also helps hold the driver in position.

If you have the opportunity before purchasing, Ashline recommends the "10 minute test." With the restraint and your helmet on, and your belts strapped down tight, simply sit in your car for 10 minutes as Hargett is doing here. This will give you a good idea whether or not the device will hinder you from concentrating on driving your car during a race.

The SFI-38.1 certification is the most stringent standard today for head-and-neck restraints. If you are serious about protecting yourself, you should make sure any restraint you purchase meets these specifications. You will know whether a restraint is 38.1 compliant because if it is it will have a sticker like this somewhere on it.

If you have the opportunity, make sure to try getting into and out of your racecar with your restraint on. If it keeps you from getting out quickly when there is a fire, the device isn't very safe after all.