ProRacing Sim, LLC is a computer software company that specializes in simulation software for the racing industry. Their featured products are the DynoSim Advanced Engine Simulation, the FastLap Sim racetrack simulation, DragSim Drag Strip Vehicle Simulation, Full Throttle Reaction Time Trainer, and the Briggs Raptor Engine Simulation software programs.

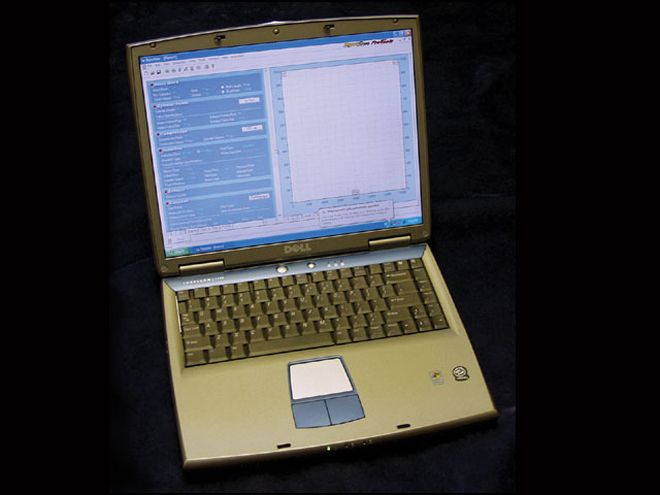

Of special interest to the readers of this magazine are the DynoSim and the FastLap Sim programs. I installed copies of these programs on my personal computer and proceeded to build my very own race motor and test it. What I noticed right away (and I have some experience with racing oriented software) is that a lot of work went into making it user friendly.

I lean toward the chassis side of racing life, but that's not to say I don't get excited about engines and power. At an early age (during the mid-'60s), I read every Hot Rod magazine I could get my hands on and developed quite a wide range of engine knowledge. Let's be honest about it, the process of making horsepower is still mostly the same. We have merely refined it with advanced parts, processes, materials, and by using remarkable new tools such as these programs.

I called up my friend Wally, with Wally's Precision Machine, who has built many of the engine types I am interested in. He helped me select the components for the motor so that it would closely resemble "within the rules" NASCAR Late Model engines raced on the East Coast in and around the Carolinas, Virginia, and Maryland.

Using the DynoSim Software I began by installing the DynoSim software and selecting an engine. I chose the generic Chevy small-block 350ci engine and then selected a 4.03-inch bore and a 3.48-inch stroke (which makes this a 355ci engine); a compression ratio of 10.8:1; a 350-cfm, two-barrel carburetor; and a dual-plane, max-flow intake manifold (to simulate a common aftermarket intake manifold). I then installed stock port heads using 1.94-inch intake and 1.65-inch exhaust valves. With the small carburetor, we find that these valves work better than the larger 2.02-inch intake valves. The cam used created 0.550-inch lift at the valve on the intake and 0.520-inch at the exhaust valve.

Once all of the numbers were in, the engine came up to 376 hp at 5,500 rpm with 438 ft-lb of torque at 3,500 rpm. Wally had said to expect between 360 and 370 hp, so this is at the high end of the range of top NASCAR LM engines. We can also play with numerous values for the cam profile and duration, intake flow numbers for our personal intake and heads if that information is known, as well as custom bore and stroke numbers to see if we can generate more horsepower or torque while staying within the cubic inch and compression ratio rules.

I tried a little experimentation at this point in the process. While working with a team years ago in a Limited Late Model class, we were running an engine exactly like the one I built here. At practice one afternoon before qualifying, the crew decided to bolt on a 735-cfm carb and went out and outran most of the Late Model cars. The pits were buzzing and, after practice, they replaced the large carburetor with the legal 350 carb. I always wondered how much horsepower they gained from that big carb. By just typing in the 735-cfm number, the graph told me I now had 439 hp at 5,500 rpm. That extra 63 hp really helped perk up that motor for us back then. For now, I put the 350 back on.

Now that I had my engine built and ready to go, the next step was to use the track-testing software to see how fast I could go.

Tuning with the FastLap Sim Software I was ready to track-test the engine in my car at my racetrack. I loaded the FastLap Sim software and began choosing my track. The closest track in the menu to a half-mile oval was New Hampshire (Loudon). Since it wasn't an exact match, I then used the Track Editor to modify the shape and size of the track until I got a size similar to the New River Valley Speedway located in Radford, Virginia. I always liked that racetrack and always wanted to race there. Now I had the chance.

Once the track was built, the next step was to install the engine I had built. I went to the engine section and opened the "pull down" menu. There are some common engines listed, and at the bottom of the list is a selection called Import DynoSim Engine File. I clicked on this, a folder manager came up, and I found the engine I had built in the DynoSim software and loaded it into my car.

The first runs were very slow. I could run a lap time of only 20.89. Because normal times at NRV were in the mid-16s, I had to go looking for more speed. A close look at the spring setup and geometry told me I had neglected to enter custom data about my car. That setup was way off. The "Generic" setup I had chosen was not even close to what I needed for this track. I simply entered the correct spring rates, wheel cambers, all of the weights, and so on, and my lap times improved significantly. But I still had a ways to go.

The real performance item I found was in "soaking" the tires. The program has a way to adjust the traction in the four tires. You can dial in the traction to get in the correct range of lap times for your track. This is good, because although you can break the track record with a high number by cheating up the tire numbers, if you get in the right range, you can then make changes to the car to fine-tune it much as you would at the track.

The primary intent of the builders of this program is to help the racer tune the engine package to the racetrack he or she will be running. The changes simulate positive and negative directions for different combinations of engine power curves. Gearing changes can be made easily, and different engines with various power and torque curve ranges can be run to determine the best configuration for an individual track related to its length and the radius of the turns. A track with long straightaways and short turns must be powered differently than one with long turns and short straights.

The overall simplicity and comprehensive features make this an excellent educational tool for every racer, even nonstock car types. I spent much more time "researching" this project than I needed because I was having a lot of fun. After tweaking the setup and engine parameters, I was able to lower my lap times to around 16.63 seconds. The normal Saturday night pole time is near the 16.40s, so I was competitive.

All of the instructions are conveniently located inside the programs and can be printed out. The DynoSim manual is 144 pages, and the FastLap Sim manual is 162 pages. The manuals include a lot of valuable information about all phases of the programs and detailed explanations of the functions.

This software does two things well: It educates us in finding the proper configuration for the engine, and it allows us to put that engine on the racetrack and further tune it against the particular track we will be racing on. That is a powerful combination we all can use.