During the 1960s, all of Detroit's entry-level cars-including pony cars-relied upon the simple leaf spring to perform rear suspension duties. Leaf springs have been around a long time, and go back to a time before cars even existed. Horse-drawn buggies had leaf springs, much to the relief of their occupants. Over time, more sophisticated rear suspensions and suspension aids were developed, including the triangulated four-link, torque arm, ladder bars, truck arms, double-wishbone independent, torsion bar, Watt's link, and Panhard bar. If you flip through the ads in PHR, you'll see plenty of great upgraded rear suspensions that use many of these technologies, but is there still a place for the lowly leaf spring? We think so!

Two clear advantages to using a leaf-spring suspension in a car that already has one are cost and simplicity. Upgrading the factory leaves with beefier ones is as easy as swapping parts. And those parts will cost less than most other options. From a functionality standpoint, a leaf spring performs three different duties: It locates the axle laterally, it fixes the axle's position around two planes of rotation, and it performs its requisite duties as a spring. That's a lot of stuff for one part to do. In more sophisticated rear suspensions, those duties can be performed by as many as four different parts. Asking one part to do all those duties has its disadvantages, namely being that a leaf spring is by necessity a compromise between competing needs.

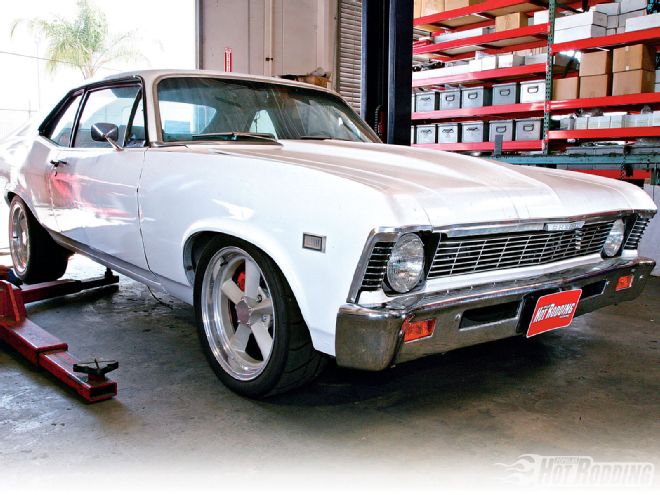

When we bought Project Nova it still had the stock monoleaf six-cylinder rear suspension and 8.2-inch 10-bolt rear. Our 523hp Dart SHP 400ci small-block could completely toast one tire through the top of Third gear! Fun, but not fast-or safe.

When we bought Project Nova it still had the stock monoleaf six-cylinder rear suspension and 8.2-inch 10-bolt rear. Our 523hp Dart SHP 400ci small-block could completely toast one tire through the top of Third gear! Fun, but not fast-or safe.

Notwithstanding, there are serious advantages to a leaf spring. With few parameters to tune, a leaf spring with the optimal spring rate, ride height, and shock valving can get you amazingly close-in terms of lap times-to suspensions costing many times that. A few years back, we tested an optimized leaf-spring setup in our 1976 Chevy Camaro project car, then swapped over to an aftermarket triangulated four-link, and found that the expensive four-link conversion had just the smallest edge over the leaf setup in the timed slalom and skidpad.

In planning our '68 Nova project, we remembered how well the leaf-spring setup worked on the g/28 Camaro, and we wanted to revisit that. When we asked Classic Performance Products (CPP) to help us with the Nova, we knew they had a leaf-spring system that was designed for hard autocross and road-race use. Project Nova was conceived with the idea that all the improvements should be easily reproduced by the average reader in a garage environment, and a hot leaf-spring setup fit that bill perfectly.

At Classic Performance Products, our new 3.08-geared Moser 12-bolt (see "12 Bolts To Glory," Dec. '10) finally met up with our '68 Nova and a pair of beefy multileaf springs and KYB Gas-Adjust shocks.

At Classic Performance Products, our new 3.08-geared Moser 12-bolt (see "12 Bolts To Glory," Dec. '10) finally met up with our '68 Nova and a pair of beefy multileaf springs and KYB Gas-Adjust shocks.

The '68-74 Nova and the '67-69 Camaro/Firebird share identical suspension architecture in the rear, and it's important to take note that across these vehicle lines there is a variation in the leaf springs and rearends between cars originally equipped with straight-six and V-8 engines. Six-cylinder cars like ours originally had monoleaf springs and monoleaf axles, and even though the engine had been swapped to a V-8 long prior to our Dart SHP 400 transplant, the spring and axle was still a monoleaf. Monoleafs do not have locating pins that lock into the axle spring perches, so when we decided to upgrade our stock rearend to a Moser 12-bolt, we ordered it with the necessary V-8 spring perches.

Even though a factory V-8 multileaf is better equipped to handle the increased torque of a factory V-8 (and will do in a pinch), it's not really up to the 523 hp (and 523 lb-ft of torque) of our Dart-based small-block, which would wrap a pair of OE multileaves into an "S" the second we hit the gas. The CPP Sport multileaf spring kit (PN 2407C, $375) is stiffer than a typical V-8 multileaf, and is 11/2 inches lower than stock. When coupled with the increased damping ability of the CPP-supplied KYB shocks (PN KY-1107, $39 each) these should put us right in the ballpark for the small-block's power, and the increased grip of our 255/40R17 Nitto NT01 R-compound rear tires.

With the rear suspension handled by Craig Chaffers and the R&D crew at CPP, we are well on our way to turning Project Nova into a credible street/strip/autocross warrior. We can't wait to flog it, but first we'll need to tackle the CPP disc brake upgrade to the front and rear, and finish it off with a quick-ratio steering gear, also from CPP. Once that is complete, we'll address our slipping Turbo 400 and see if we can improve the exhaust with a larger set of Hooker headers.

In comparing the old monoleaf six-cylinder leaf spring with the CPP Sport multileaf V-8 spring, you'll notice two things: The greater stiffness of the CPP Sport spring means it has much less of an arch, and the CPP spring has a locating pin that fits in a receiver hole in the axle spring perch. If you decide to upgrade your springs using a 10-bolt monoleaf axle, the Sport kit has the extra set of urethane spring pads to receive the locating pin on the spring, allowing you to use the V-8 spring.

In comparing the old monoleaf six-cylinder leaf spring with the CPP Sport multileaf V-8 spring, you'll notice two things: The greater stiffness of the CPP Sport spring means it has much less of an arch, and the CPP spring has a locating pin that fits in a receiver hole in the axle spring perch. If you decide to upgrade your springs using a 10-bolt monoleaf axle, the Sport kit has the extra set of urethane spring pads to receive the locating pin on the spring, allowing you to use the V-8 spring.

Driveshaft Solution

As our '68 Nova project becomes transformed from a grocery getter to a Corvette beater, we've had to integrate the new suspension with a beefier rearend, and take into account our future transmission plans. Like many other projects, different transmissions, rearends, and suspensions can dictate a custom driveshaft to make it all work together. Even in rare cases where dimensions don't change, sometimes you need more beefcake in the prop shaft, or you need a stronger yoke assembly. No matter what your need, Inland Empire Driveline Services can build the right piece.

We've been proceeding with the suspension, steering, and brake upgrades at Classic Performance Products, and IEDS was glad to help. IEDS sent out driveline tech Jesse Lopez to take our measurements and get a handle on our power transfer requirements. The first thing Lopez did was determine that our Turbo 400 had an internal O-ring in the output shaft, as indicated by the threaded hole in the shaft end. This determines how the new yoke is machined and is very important to note when ordering.

Next, Lopez measured the distance between the end of the tailshaft and the mating face of the pinion cap (it was 54 5/8 inches with our Moser 12-bolt). The inside diameter of the cross-shaft at the rear pinion was noted at 1 3/16 inches, and the output shaft length protruding beyond the tailhousing was noted. Lopez also asked some questions about the power output of our Dart SHP 400 and our intended use (autocross, cruise, road race, and occasional drag race), then suggested an aluminum shaft.

After removing the old 10-bolt from the Nova, Craig Chaffers of CPP removed the body-mounted forward spring perches and the axle-mounted shock perches. These need to be reused, so we decided to sandblast them and give them a new coat of satin-black spray paint.

After removing the old 10-bolt from the Nova, Craig Chaffers of CPP removed the body-mounted forward spring perches and the axle-mounted shock perches. These need to be reused, so we decided to sandblast them and give them a new coat of satin-black spray paint.

One cool thing about IEDS is that they build each driveshaft as a custom order-there are no off-the-shelf units because most every hot rod or race car is different. For that reason, IEDS offers on-location service to local customers like us. When the people who build them are doing the measuring, it takes all the guesswork out of the equation. When they're done measuring, they build your driveshaft, balance it, and deliver it locally within 48 hours, guaranteed.

WHERE THE MONEY WENT DESCRIPTION: NOTES: COST: CPP Sport multileaf spring kit fits '68-74 Nova and '67-69 Camaro $375 KYB Gas-Adjust shocks CPP PN KY-1107 $39 ea. Inland Empire driveshaft aluminum, 1350-series yoke $535 Total: $988