Find a useful steering box candidate out of the local yard, clean it up, and bolt it on your Chevelle, Camaro, or Nova to get rid of that vague '60s steering.

Find a useful steering box candidate out of the local yard, clean it up, and bolt it on your Chevelle, Camaro, or Nova to get rid of that vague '60s steering.

Drive a new Mustang, Challenger, or Corvette and then slide behind the wheel of a '60s muscle car and it takes about a minute to realize that ride quality, handling, and performance feel have evolved quite nicely in the last 40 years. The first thing you notice is how that new car steering wheel has a direct connection to the road, while that '60s muscle car feels like a soggy bowl of porridge. In fact, we've driven some of the more upscale computer simulations that have better feedback through the steering wheel than a stock '64 Chevelle. The good news is there's an easy fix for this vagueness if you own a '64 to '72 Chevelle, '67 to '81 Camaro, or '68 to '74 Nova. And the parts are no farther away than the local boneyard.

Back in the '60s, GM thought the one-finger approach to twirling the steering wheel in a parallel parking exercise was the blue-ribbon pass for the ultimate driving experience. While that might have been great for your grandmother in 1965, any track day junkie will tell you it's the effort and feedback through the steering wheel from the front tires that is part and parcel of the handling holy grail. Beginning in the late '70s and through the '90s, GM's classic recirculating ball steering box has drastically improved steering feel and, as you might guess, there are almost as many different versions of this box as Pamela Anderson has plastic surgeons in her Rolodex.

Several years ago, certain steering boxes had surfaced as ideal junkyard swaps for these early Chevys. To be accurate, this swap will also work for any early A-Body, such as a Pontiac, a Buick, or an Oldsmobile and also first- and second-generation Camaros and Firebirds. All the demand for these good boxes, such as the '85 to '88 Monte Carlo SS box, has put a crimp in the supply. We drilled a little deeper into the GM steering box grab bag and discovered several other body styles that are excellent candidates for this swap. We also spent a day with Tom Lee at Lee Manufacturing, the guru of steering box science who builds steering boxes for Sprint Cars, Cup cars, and many of the hard-charging off-road racers who are masters of steering box abuse. The beauty of all this is that the knowledge transfer that trickles down from race cars will make your street car box a real treat.

Best Buys

The following condensed chart was derived from a much longer original created by Jim Shea, which appears on the Team Chevelle web-site formatted by Wes Vann and used with permission. If you would like to see the entire spreadsheet, it can be found at chevelles.com/techref/ftecref29.html. Shea has also posted updated references on the corvettefaq.com website. Just look for the Jim Shea's Steering Papers notation in the upper righthand corner of the page. Jim also goes into great detail on modifying the steering column to mount the new flexible coupling, which we don't have room to detail here.

Depending on the year of the car, this swap will require modifying the steering column flange where it connects to the coupler. The best thing to do is remove the column from the car and widen the smaller of the two drive-pin notches with a die grinder about 0.070 inch. Then test-fit the flange to the coupler and determine which bolthole needs to be drilled out with a 3/8-inch drill bit.

Depending on the year of the car, this swap will require modifying the steering column flange where it connects to the coupler. The best thing to do is remove the column from the car and widen the smaller of the two drive-pin notches with a die grinder about 0.070 inch. Then test-fit the flange to the coupler and determine which bolthole needs to be drilled out with a 3/8-inch drill bit.

It's also important to explain what each of these columns represents. The body style and year columns are obvious. The code is the ink stamp found on the end of the aluminum end cover that is often very difficult if not impossible to read. Ratio refers to the number of degrees of movement of the steering wheel that will produce a 1-degree rotation of the output shaft. With a 12.7:1 gear ratio, for example, moving the steering wheel 12.7 degrees equals one degree of rotation of the output shaft. The lower the ratio number, the quicker the output shaft moves, and the quicker the steering. Keep in mind this steering gear ratio is also affected by the length of the pitman arm and steering arms located on each spindle, creating an overall steering ratio. This overall ratio is often slower than the ratio in the box. The effort and T-bar columns give a good indication as to how much effort it will take to steer your car. The larger the T-bar diameter, the higher the effort to obtain power assist. The effort column refers to a laboratory test where hydraulic oil is circulated through the gear and a torque (in-lb) determined to create a specific amount of assist pressure. Even a 5 in-lb difference in effort is noticeable. Higher effort boxes are generally accepted as performance-oriented boxes. The total travel column indicates the distance the pitman arm sweeps from full lock to full lock and is expressed in degrees and minutes (60 minutes in one degree). This is an important measurement when it comes to swapping boxes between different body styles.

SAGINAW POWER STEERING BOXES BODY STYLE YEAR CODE RATIO EFFORT T-BAR TOTAL TRAVEL Monte Carlo SS ’85 to ’88 YA 12.7:1 24-30 0.204 78 degrees 30 minutes Fullsize Chevy F-41 '88 to '90 WZ 12.7:1 20-26 0.195 87 degrees Fullsize Chevy F-41 '91 to '94 CP 12.7:1 17-22 0.185 87 degrees Fullsize Chevy F-41 '95 CT 12.7:1 19-22 0.185 87 degrees Camaro/Firebird ’82 to ’93 WS 12.7:1 24-30 0.185 70 degrees Camaro with FE2 ’85 to ’93 XH 12.7:1 28-34 0.210 64 degrees Camaro ’67 -- 17.5:1 15-21 0.175 87 degrees Camaro ’68 to ’81 -- VR* 14-22 0.175 67 degrees Chevelle ’66 -- 17.5:1 15-21 0.175 87 degrees

*Most Camaros in these years had variable ratio gears (16:1 on center, 13:1 near full lock); '79 to '81 Z28s had 14:1 ratio gears.

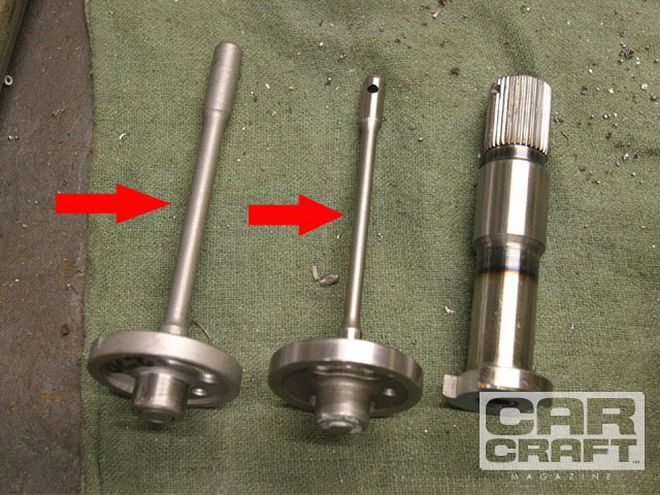

Note how the police version pitman shaft (left) has a double-wide locator spline (arrow) compared with the standard blind spline for all the other applications. This wider blind spline allows a standard pitman arm to assemble to the shaft on two possible spline positions. Set the steering gear on-center and assemble the pitman arm on the spline that places it along the centerline of the gear.

Note how the police version pitman shaft (left) has a double-wide locator spline (arrow) compared with the standard blind spline for all the other applications. This wider blind spline allows a standard pitman arm to assemble to the shaft on two possible spline positions. Set the steering gear on-center and assemble the pitman arm on the spline that places it along the centerline of the gear.

Interchangeability

Perhaps the greatest legacy that GM has handed down to car crafters is interchangeability. For this story, that means many of the steering boxes used in various body styles as late as the '90s can be retrofitted into classic '60s cars. But there are certain land mines that have to be negotiated to create a successful steering box swap. For example, one of the most popular power steering box upgrades for an early Camaro, Chevelle, or '68 to '74 Nova is the '85 to '88 Monte Carlo SS box. There were also a few Pontiac, Olds, and Buick G-Body cars that used similar boxes. The difficulty with this swap is that demand is far greater than supply, which makes finding one of these boxes difficult. This means we have to look for alternative boxes that will do the same job. Another popular swap candidate is the third-generation ('82 to '93) Z28 Camaro or Pontiac Trans Am steering box. In the application chart, you can see the WS and XH boxes (among others) offer an excellent 12.7:1 fixed ratio. What is not so good for A-Body, early Camaro, and Nova owners is the third-gen Camaro box's limited 64- to 70-degree pitman arm sweep. Compared with a stock Chevelle/Camaro/Nova movement of 87 degrees, this means that bolting in an '89 Camaro steering box drastically reduces the early car's turning radius. We've tried a third-gen Camaro box on a '65 El Camino and discovered that while the ratio improved and the feel is much better, the lost turning radius makes the car less fun to drive, requiring three-point turns where a simple U-turn was achievable with stock steering. There is a way to change the stops in the third-gen Camaro box to remedy this situation. We'll get into steer-ing box modifications with Lee Manufacturing in a subsequent sidebar, but the key point here is to use the application chart as a guide for choosing the best box for your application.

The chart also indicates that the fullsize Chevy (and possibly Buick, Pontiac, and Oldsmobile) B-Body styles offer a better alternative as a bolt-in performance style steering box. Note that the WZ box is better than the other two listed here because it has the highest effort while retaining the 12.7:1 ratio and matching 87-degree pitman arm sweep. These big-car steering boxes have received very little attention in the performance press yet offer most of the same characteristics as the highly prized Monte SS box. Tom Lee of Lee Manufacturing told us that the fullsize Impala police car steering boxes look like an ideal swap with high-effort numbers. However, the machined splines on the police car gear output shaft are different from all other Saginaw power gear shafts. Instead of machining out a single spline in each quadrant of the output shaft, the police car shaft has two adjacent splines machined away in each quadrant. The splines in the special police car pitman arms have double blocked teeth to match. Since the Chevelle pitman arm has only a single blocked tooth in each of its quadrants, you will be able to assemble that pitman arm at two possible spline positions on the police car gear. To install a Chevelle pitman arm on a police car gear, first set the steering gear exactly on center (flat on the input shaft pointing straight up.) Then install the pitman arm on the output shaft spline that places the arm exactly on the centerline of the gear.

Installation Tips And Tricks <strong>Installation Tips And Tricks</strong><br>Lee builds steering boxes for many major race organizations as well as street cars. He recommends an external reservoir for the power steering pump. Lee's reservoirs use a sealed cap that maintains 10 psi of residual pressure to improve steering pump efficiency. A large reservoir is not necessary. All the GM sheetmetal reservoirs that are integral to the pump also work very well. All plastic GM power steering reservoir caps over the last 30 years have incorporated check valves to create some residual pressure.

<strong>Installation Tips And Tricks</strong><br>Lee builds steering boxes for many major race organizations as well as street cars. He recommends an external reservoir for the power steering pump. Lee's reservoirs use a sealed cap that maintains 10 psi of residual pressure to improve steering pump efficiency. A large reservoir is not necessary. All the GM sheetmetal reservoirs that are integral to the pump also work very well. All plastic GM power steering reservoir caps over the last 30 years have incorporated check valves to create some residual pressure.

While a late-model B-car or Monte power steering box swap appears simple, there are a couple of small parts you will need to complete the conversion. Steering boxes for the early '64 to '75 cars used a 13/16-inch-diameter input shaft with 36 splines. After 1976, all GM power steering boxes were changed to a smaller 3/4-inch input shaft with 30 splines. The newer, fast ratio boxes all have the 3/4-inch input shaft with 30 splines. This requires a steering coupler (also called a rag joint) that will fit on the new box input shaft and also bolt up to the older steering columns. Luckily, the '77 to '82 C/K and the two-wheel-drive '83 to '86 Chevy and GMC trucks, as well as the '77 to '78 Camaro, Firebird, and Nova also used this style coupler. We've listed both the original GM steering coupler and aftermarket part numbers that you can use to make this connection.

In the '80 model year, GM also changed from its original 45-degree inverted flare 5/8x18 UF and 11/16x18 UNS female fitting sizes to a metric O-ring (often called Saginaw fittings) measuring 16x1.5 mm and 18x1.5 mm. Coincidentally, the thread pitch of these metric fittings is almost identical to the original fittings, which led Lee to develop aluminum press-in inserts that convert the newer O-ring-style sealing back to inverted flare fittings. Because the thread pitch for both fittings is almost identical, these inserts allow you to use your original inverted flare hoses and fittings.

Included in Jim Shea's original outline is a listing of '92 through '98 Jeep Grand Cherokee steering boxes, all with 12.7:1 gear ratios and 20- to 26-in-lb efforts and the attractive 87-degree travel figures. We did not include these references in this story, but the above Internet references will get you there in a hurry.

The arrows point to the section of the torsion bar that creates the resistance to movement in the input shaft and establishes the box's feel. A larger torsion bar causes more resistance before hydraulic power assist becomes available.

The arrows point to the section of the torsion bar that creates the resistance to movement in the input shaft and establishes the box's feel. A larger torsion bar causes more resistance before hydraulic power assist becomes available.

Internal Box Modifications

We spent a day at Lee Manufacturing, where owner Tom Lee showed us a few internal components that make up a typical Saginaw power steering box. He doesn't recommend rebuilding your own box. Rebuilding a Saginaw power steering box requires specialty tools and experience, and a poorly assembled box could lock up, which is something you should clearly strive to avoid. Cruising through the junkyard for a suitable box for our '64 Olds, we chose a used '88 F-body WS box that we took to Lee to rebuild. Lee takes the time to carefully blueprint each box, replace any worn or damaged parts, and upgrade the components to fit your requirements. In the case of our third-generation Camaro box, he changed the internal stops in the box to lengthen the pitman arm arc required to give a GM A-body car its proper turning radius.

If you choose to have Lee rebuild a late-model box, there are several options. For example, Lee can easily change the torsion bar in a large-car (B-body) box to increase the effort, but that requires completely disassembling the box. Lee does not have a set price for rebuilds, since each one is a little bit different, but he did give us a range of around $225 to $250 if he starts with a good, rebuildable box.

Variable- Ratio Boxes

Here is where personal preference may come into play. Lee feels the best steering box is the one that is the most consistent, which is why he prefers a fixed-ratio box for performance driving applications. Variable-ratio boxes feature a slow ratio from center that becomes quicker as the steering wheel is turned away from center. A typical variable-ratio box will feature an on-center ratio of 16:1 that changes to 13:1 toward the end of the travel. Variable-ratio boxes generally don't offer faster ratios than fixed-ratio boxes.