Face it, if like-new or maybe even better-than-new performance is what you want from your Mopar's suspension, it will likely need a comprehensive rebuild. Under normal use, the stock Mopar front suspension lasts about 100,000 miles. The fact is, even with fewer miles under hard use or over a long period of time, things can get mushy; and, unfortunately, the required chassis lube-job has become an almost-forgotten routine.

The Mopar torsion-bar suspension was perhaps the finest front-suspension design of the period because of Chrysler's innovative and efficient torsion-bar springing and unequal-length control arms. The system featured torsion bars hex-anchored to a ridged mid-chassis-mounted crossmember and keyed to the lower control arm by an adjustable mounting socket. In turn the lower control arm is secured to the solid K-member via a rubber-bushed pivot shaft. The lower control arm is triangulated to the K-member by a forward-facing strut rod that forms the second leg of the lower A-arm. The strut rod solidly transfers the fore and aft forces of the front suspension during braking, acceleration, and cornering. The upper A-arm is formed like a conventional wishbone, pivoting on two inner bushings. The spindle mounts between the upper and lower control arms via two large spherical ball joints.

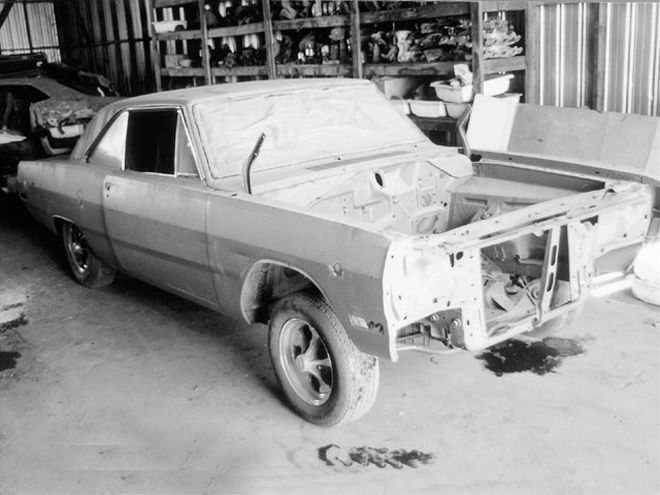

This '70 Swinger 340, now a rolling chassis, will get a better-than-new front suspension.

This '70 Swinger 340, now a rolling chassis, will get a better-than-new front suspension.

Most trouble begins with the ball joints. It's internally supported by low-friction nylon inserts that require routine lubrication. After the factory lube, the grease fittings were snapped, requiring the fitting of new zerks for service lubrication. All too often the service lube never happened, resulting in worn-out ball joints. The same situation occurs with many ball-jointed tie-rod ends.

Next we have the bushings. The most critical bushing in the system is in the lower control arm. The pivot shaft is rigidly mounted to the K-member, and the torsion-bar socket at the other end pivots with the lower control arm. This disparity in motion is wholly absorbed through the twisting rubber in the lower control-arm's pivot-shaft bushing. Eventually the twisting takes its toll and the bushing fails. Then we have the strut rod, rigidly mounted to the lower control arm but bushed at the forward K-member mount to allow for articulation through the suspension's motion. The forces on the strut bushings are primarily fore and aft, and whenworn, they cause the lower control arm to shift forward and back at the ball-joint end, making the suspension unstable. Up top, the rubber upper control-arm bushings are subject to normal wear, and they too eventually blow out.

Bed rest doesn't do the suspension any good; the only cure is a rebuild. The best approach is to blow it all apart and replace everything, using an aftermarket rebuild kit. This '70 Dart Swinger 340 is in the process of a full rebuild, and a fresh front suspension is on the list. While rebuilding the front suspension piecemeal on the car is the norm for service, in a resto, pull the entire works from the chassis in one hit. The bulk of the suspension and steering system is mounted to the K-member, allowing removal as a unit by dropping the "K."

Though rebuilding the suspension in the car while lying on the cold concrete can be some seriously dirty penance, with the K-member out the job is nothing short of enjoyable. A number of tricks we've developed over the years make the job easier. This month, we'll cover the removal of the complete K-member and front suspension from the car, and weld-up a rig that allows us to mount the K-member to an engine stand for service. We'll show what it takes to break it all down and pass on the hard-learned tricks of the game.