With LS swaps all the rage these days, it’s easy to forget big-blocks are still alive and thriving. That’s because when it comes to making big power and even bigger torque, building it with a big-block is as easy as goading a smug Mustang driver into embarrassing himself at the stoplight.

Most enthusiasts know the basic big-block cylinder block casting was updated in the 1980s, but fewer know General Motors quietly updated the basic design of the block casting only a few short years ago to give it greater strength, greater performance capability, and make common much of the differences between the early, Mark IV blocks and later, 1980’s-type Gen V castings.

Big-block production engines were introduced, of course, in 1965 and remained in production with few changes for more than 20 years. Those are the Mark IV engines. In the late 1980s a new version arrived, designed primarily for marine and automotive fuel-injection applications. Those updated versions are referred to as the Gen V (and Gen VI) engines.

Distinguishing between Mark IV and Gen V blocks is easy: if it has a mechanical fuel pump mounting pad, it’s a Mark IV. If there’s no fuel pump pad, it’s a Gen V block. There are several other differences—particularly in the water jackets near the deck surfaces—that make some Mark IV and Gen V parts non-interchangeable, including crucial components such as cylinder head gaskets.

Within the last few years, General Motors revised the production-based big-block casting to accommodate features of the Mark IV and Gen V, enabling cylinder head and gasket interchangeability. It also features a mechanical fuel pump pad recast into the architecture. Other, less-visible changes to the basic casting include revised oiling to allow for larger camshaft bearings, thus higher camshaft lift. There has also been talk of creating extra clearance for roller timing chains, but as of our press deadline, that change hadn’t been implemented.

The latest block design is available from Chevrolet Performance (chevrolet.com/performance) under part numbers 19170538 and 19170540. The “0538” version comes with 4.250-inch finished bores to support 427- and 454-cubic-inch engines, while the “0540” block has larger-diameter 4.470 bores to build a 502-inch engine. Each can be overbored for a larger displacement, with the 0540 block supporting up to 4.500-inch bores. Notably, all of Chevrolet Performance’s crate engines use the revised casting design.

If you’re looking to build a mountain motor with an even larger bore, you’ll have to look at Chevrolet Performance’s Bowtie blocks, which support up to a 4.600-inch bore, or an aftermarket block.

For strength and parts interchangeability, the big-block castings’ specific changes and updates include a slightly beefier main web on the 0538 block, while both versions have revised water jackets near the deck surfaces, allowing Mark IV or Gen V head gaskets to be used interchangeably. The front bulkhead is revised, too. It is thicker and stronger, with marked provisions for a 10-bolt timing cover. Actually, the bulkhead is drilled and tapped for a conventional six-bolt cover, while the remaining holes must be finished by drilling out the prescribed positions. There is more material around the lifter bosses and a revised rear-of-block section allows for the machining of one- or two-piece main seals (similar to the Gen V design).

Oil pressure feed holes were added to the oil filter boss and front bulkhead to support oil feeds for superchargers, turbochargers, etc., while the oil hole next to the camshaft bore (at the front of the block) was repositioned to enable safe machining of the cam bore to accept a 50mm roller camshaft bearing. A new boss was added next to the distributor hole in the valley to support hardware for digital ignition equipment, and a front clutch boss has been added for older vehicle applications.

Also, a pair of new core plugs was added to the rear bulkhead. Chevrolet Performance says they enhanced the manufacturing process at the foundry and help improve overall quality. Also, a “Bowtie” emblem and other identifying marks were added to the Bowtie block, distinguishing it from previous castings.

In addition to the production-based “Mark”-type casting, Chevrolet Performance’s Bowtie block castings are designed for the highest-performance applications. They feature a few minor differences when compared with the Mark block, but include the common core’s updates for greater interchangeability. Most notably, the Bowtie blocks are machined for splayed main bearing cap bolts, whereas the “standard” versions feature production-style parallel main cap fasteners. The Bowtie blocks also have a distinctive water jacket design that allows the 4.600-inch bore capacity. There are seven part numbers offered for Bowtie blocks, some with the standard 9.800-inch deck height and one-piece rear main seal, and others with a tall, 10.200-inch deck height and two-piece rear main seal design.

There you have it: The big-block is renewed and improved after more than 50 years of stalwart performance. The updates will keep big-block engines viable for the foreseeable future and continue to prove the adage that there’s simply no replacement for displacement.

The latest big-block casting has undergone significant updates to align the differences that distinguished earlier Mark IV and later Gen V blocks, while also strengthening the block and adding provisions that support greater performance.

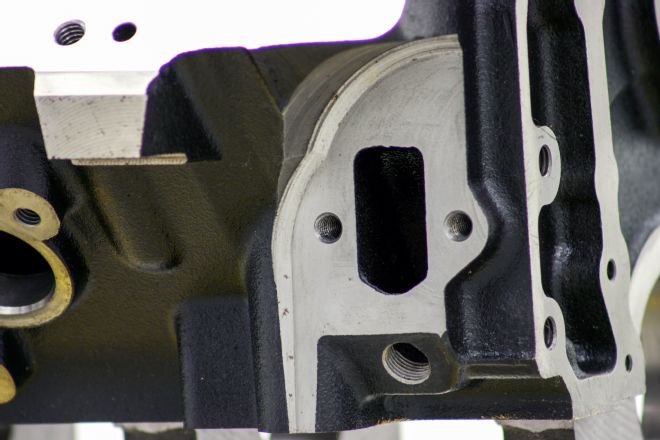

The most noticeable visual change to the latest design is the reintroduction of a mechanical fuel pump mounting pad machined into the passenger-side front corner of the block. Gen V blocks did not have this provision.

The front of the block was revamped for greater parts interchangeability with the Mark IV and Gen V, including using 6-bolt or 10-bolt timing chain covers. (It comes with the 6-bolt cover holes machined, but is easily drilled and tapped for the 10-bolt cover.) Also, a Bowtie-style auxiliary pressurized oil line hole is machined near the bottom of the China wall.

A revised oiling design (the oil hole next to the cam bore was repositioned) allows the camshaft bore to support the 50mm bearing of a roller-style, high-lift camshaft.

The valley is mostly unchanged, but is machined for a roller-type valvetrain with more material cast around the lifter bosses. Also, a bolt boss is added next to the distributor boss to support digital ignition systems.

Deck height specs remain unchanged at 9.800 inches for production-based blocks, but the water jackets beneath them are revised so that early Mark IV-type and later, Gen V-type head gaskets can be used interchangeably. Some versions of the Bowtie block are offered with a 10.200-inch deck height.

The rear of the block casting is updated with a common core that enables the machining of one-piece or two-piece rear seals. This permits the engine to be fitted with and dressed like an early Mark IV engine, albeit with the modern block casting.

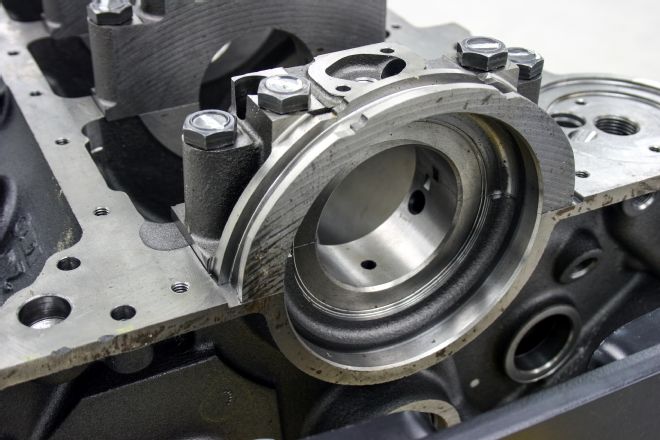

There are subtle changes to the interior bulkheads that incorporate the Bowtie design into 8.2L Mark blocks; the smaller-displacement 7.4L Mark block is unchanged, due to knock sensor accommodations. There are subtle machining updates, too.

All Mark-type blocks—such as the one seen here—are manufactured with production-style parallel four-bolt main caps. The race-oriented Bowtie casting features splayed mains.

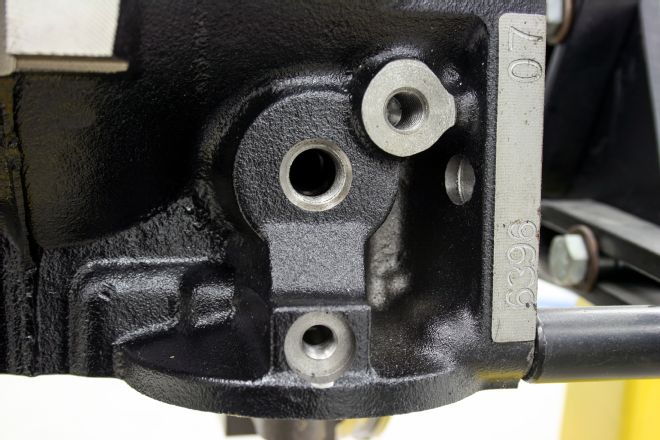

The rear of the block features new plug holes, similar to what GM did with the small-block casting.

A new hole (shown at the very bottom of the photo) is added to the oil filter boss on the block to support a pressurized oil feed.

Another major addition to the big-block casting is a clutch equalizer boss that makes the block a better fit for vintage muscle cars and their four-speed transmissions.

Big-Block Milestones: A Journey of Expanding Cubic Inches

The Chevy Mark IV big-block was born out of the “W” engine program that spawned the famous 348 and 409 engines—as well as the infamous 427-inch Z-11 engine. It debuted as Chevy’s “Mystery Motor” that traded the W engine’s unique valve setup for a more conventional design, and powered the suspiciously fast Chevys at the 1963 Daytona 500.

When the Mark IV was installed in production vehicles for the first time in 1965, it carried the Turbo-Jet name on the air cleaner, displaced 396 cubic inches, and was rated at a maximum of 425 horsepower in the Corvettes.

Here’s a quick look at milestones in the big-block’s expanding and contracting history of displacement:

396 cid – introduced in 1965, with 4.094-in. x 3.760-in. bore and stroke (first production Mark IV engine).

427 cid – introduced in 1966, with 4.250-in. x 3.760-in. bore and stroke (aluminum versions used in COPO supercars).

366 cid – introduced in 1968, with 3.935-in. x 3.760-in. bore and stroke (tall-deck; used in truck applications).

402 cid – introduced in 1970, with 4.125-in. x 3.760-in. bore and stroke (advertised as 396 cid).

454 cid – introduced in 1970, with 4.250-in. x 4.000-in. bore and stroke.

502 cid – introduced in 1988, with 4.466-in. x 4.000-in. bore and stroke (Gen V block, originally developed for non-automotive applications; adapted later by Chevrolet Performance).

572 cid – introduced in 2003, with 4.560-in. x 4.375-in. bore and stroke (developed by Chevrolet Performance; no production vehicle applications).

Wait … What? A SOHC Big-Block?

This photo was buried in Chevrolet’s archives and shows prototype hemispherical heads with single overhead cams on an early Mark IV big-block, circa 1965-’66. No doubt inspired by the similar arrangement Ford introduced a couple of years prior—which was itself a response to the Chrysler Hemi used in NASCAR. Almost nothing is known about this experimental engine, which used a long, continuous three-row timing chain to drive both camshafts (note the placeholder gear in place of the conventional camshaft, which is directly connected to the crankshaft). That might have contributed to the engine’s lack of further development because, as Ford SOHC tuners found out, the inherent slack in the long chain made timing annoyingly finicky—typically requiring substantially staggered timing between the cylinder banks. A gear-drive system would have solved the problem, but at significant cost. NASCAR forbade the Ford SOHC altogether and banned the Chrysler Hemi after the 1964 season, so there was little incentive to continue work on this complicated big-block variant. It’s still a fascinating piece of history—and check out the unique valve arrangement from the shaft-mounted rocker arms. We can only speculate what might have been if this hemi-headed “sock” big-block had been unleashed at, say, the Daytona Speedway or Talladega!