As we said in “A Tale of Two Chevys – Part 1,” the plan to build a pair of Gen I Chevrolet small-blocks came into being during one of those “Wouldn’t it be cool to do” bench racing sessions with John Beck of Vintage Hot Rod Design. The conversation centered on building what would now be considered vintage engines, both destined to power hot rods that would be regular drivers with reliability and driveability more important than huge horsepower numbers.

As the discussion continued the elements of both engines went from fuzzy to focused. John wanted to build a blown 302-incher and we wanted to breathe life back into a 283 that was sitting in the corner of our shop and top it with three two-barrel carburetors. Thanks to Weiand and Holley that’s just what we did. Weiand had just come out with their nostalgic 6-71 supercharger kit and Holley introduced their new Tri-Power setup—what other choice did we have? It was time to build a pair of engines.

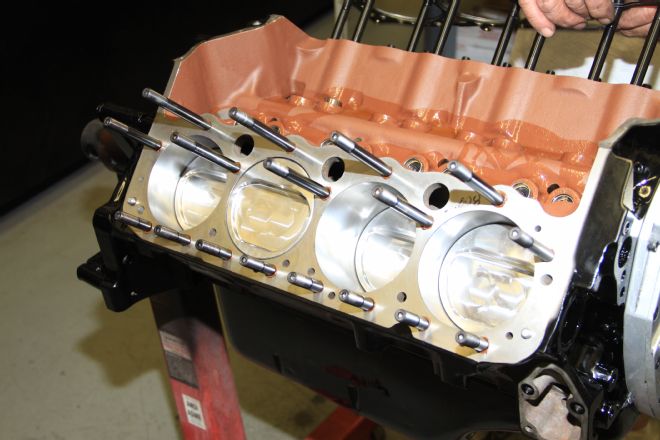

In Part 1 we covered the building of both short-blocks; but to recap, John’s blown engine is based on a large-journal 350 block overbored 0.030 inches to 4.030 inches coupled with a 3.00-inch stroke 302 crankshaft, resulting in 306 cubic inches. Our 283 block was sonic checked then overbored 0.060 inches to 3.935 inches and combined with a 3.25-inch stroke 327 crankshaft for a displacement of 316 cubic inches.

Heads

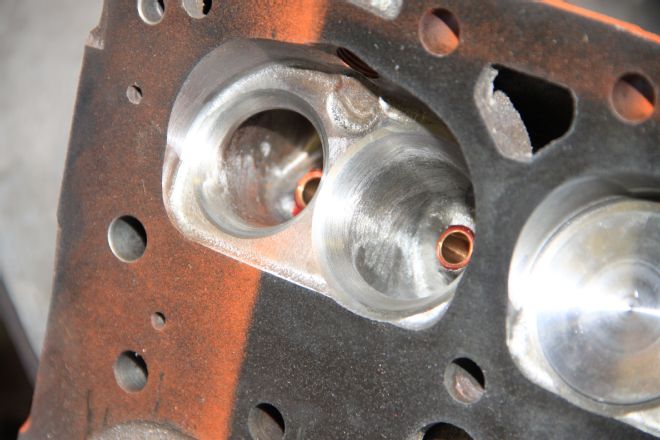

Sticking with the vintage theme, both engines use early cast-iron cylinder heads (pre-1969 style without accessory mounting holes). The naturally aspirated engine uses Power Pack heads (dated January 1961). John installed larger valves, but the proximity of the new 2.02-inch intake and 1.60-inch exhaust valves to the edges of the chambers prompted some concern about shrouding. In other words, flow could actually be restricted in those areas, and the advantages of bigger valves would be lost. The cure was to reduce the intake valves to 2.00 inches and widen the areas of the combustion chamber closest to the valves. Additional headwork was done to open up the bowls and smooth the intake and exhaust ports.

The heads for the blown engine are “camel hump” castings from 1967-’68 equipped with 2.02-inch intake and 1.60-inch exhaust valves. The bowls and ports were opened up and smoothed, but because these heads were so much better to begin with they required considerably less effort than the Power Pack heads.

As we said, some of the shared goals for both engines were reliability and longevity—to that end, compression ratios were kept on the conservative side. The combustion chamber size, piston design, and deck heights were coordinated to provide compression ratios of 7.1:1 for the blown engine and 9.6:1 for the naturally aspirated engine.

Ignition

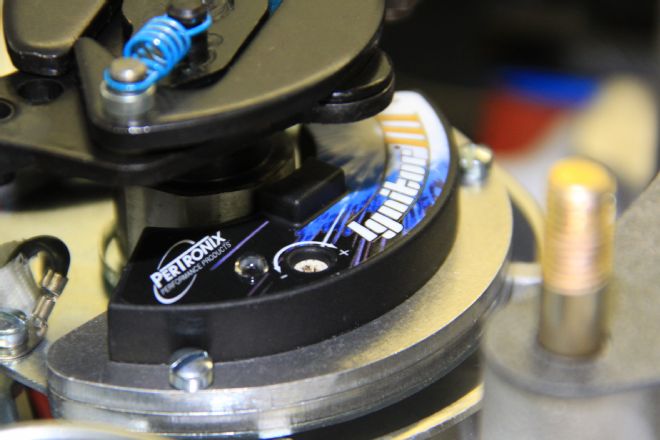

For ignition systems we wanted distributors that looked like vintage points-controlled units but had all the latest electronics under a small-diameter cap. To give us what we needed, we turned to PerTronix for a pair of their Flame-Thrower plug-and-play distributors. The Ignitor III technology provides multiple sparks over the entire rpm range and there is what is called “adaptive dwell,” which maintains peak spark energy throughout the entire rpm range.

Induction

When it comes to induction systems, there are two distinct methods of making a statement: a trio of carburetors or a 6-71 blower.

Tri-Power is the stuff legends are made from. Not only do they look cool, but they’re really practical, too. Holley’s new system uses a Weiand 3x2 intake manifold with three Holley two-barrel carbs. The center carb is rated at 325 cfm and is equipped with a choke, whereas the outboard carburetors have no chokes and are rated at 350 cfm each. Thanks to the included progressive throttle linkage you can cruise around on the center carburetor for economy, but as the throttle pedal passes the two-thirds point, the outboard carburetors come online and all three reach wide open simultaneously.

Holley’s Tri-Power kits are available with dichromate or shiny finish carburetors. Fuel lines, progressive linkage, and reusable air filters with polished housings are included.

For a variety of reasons, vintage blowers were getting hard to come by—a situation that Weiand decided to address by introducing redesigned 6-71 cases. The vintage no-name look makes them appear right at home on a street engine or a cackelfest dragster.

Inside these all-new blower cases are roots-type, two-lobe rotors. The heavy-duty rear plate uses sealed ball bearings to support the rotors; up front, the bearings and gears are lubricated by an oil bath. Weiand’s nostalgic supercharger kits include a polished or satin 6-71 supercharger with gears and bearing plates, supercharger intake manifold, 2-4V carburetor adapter, all the required gaskets, 3-inch Gilmer belt, pulleys, brackets, idler, and necessary fasteners.

All Weiand’s superchargers are boost-tested and engineered to produce 10-12 psi of boost on small-blocks and 5-7 psi on big-blocks, but as they say, these blowers are a simple pulley change away from pump gas or hard-core racing.

Testing

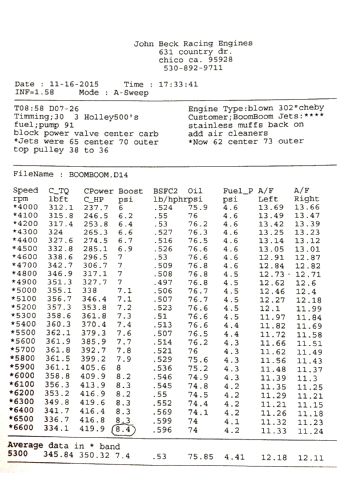

The blower on John’s small-block was topped with the same carburetor setup as our naturally aspirated engine, and it too used a progressive throttle linkage to operate them. The engine pulled willingly from idle, and after some jetting adjustments, the little 306 made 419 horsepower and 362 lb-ft of torque breathing through air cleaners, exhaling through mufflers and we discovered we weren’t getting full throttle—nonetheless we were happy. The engine idles smoothly and the throttle response is instantaneous.

Other than building something unique, we had modest horsepower and torque goals for our little naturally aspirated engine. We were shooting for 325 horsepower and as broad a torque curve as possible. Frankly, we just wanted it to be in the neighborhood of what a carbureted 5.3L LS would produce because that’s the engine we were originally going to use in our latest hot rod but couldn’t bring ourselves to go new school.

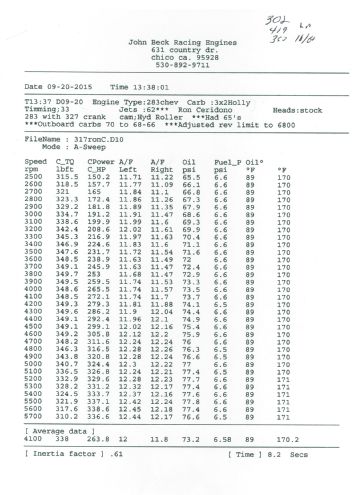

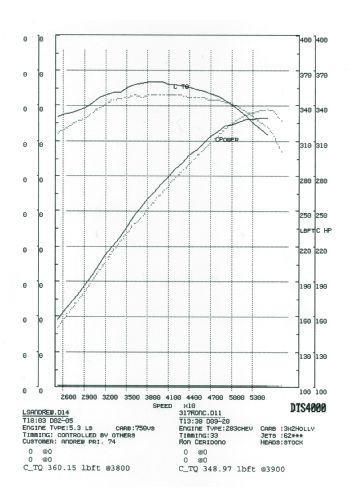

When the testing began we were concerned that with 1,025 cfm our little naturally aspirated engine would be way over-carbureted, but there was no indication that was the case. After changing the jets in the center carburetor from 65s to 62s, and going from 70s to 68s in the end mixers we saw 338 horsepower and 349-lb ft of torque (with a 338 lb-ft average from 2,500 to 5,700 rpm). For giggles, we tested a carbureted LS1 and it produced 360.15 lb-ft of torque, but because our engine looks so much cooler, it doesn’t bother us.

In the final analysis, both engines more than met our goals—good power; reasonable fuel consumption; and great, vintage visual appeal. Those are tales worth telling.

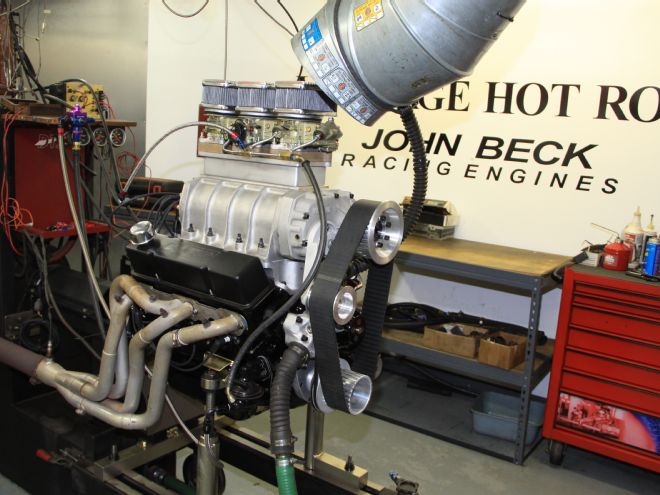

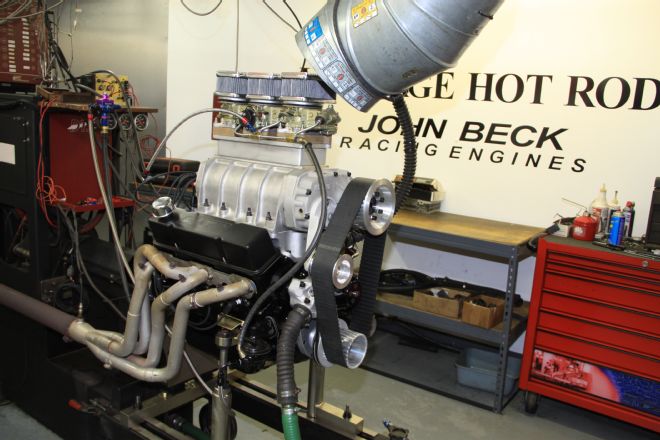

John Beck’s old-school Weiand blown, Holley-carbureted 306-inch small-block is just about ready to be fired for the first time.

Waiting its turn on the Vintage Hot Rod Design dyno is our naturally aspirated, Tri-Power-equipped 316. Water pumps on both engines are from Weiand, this engine uses a Rattler crank damper.

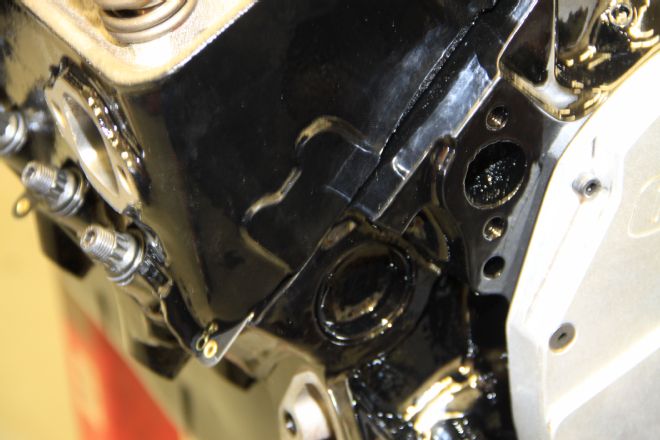

For the naturally aspirated engine, the 283 block was fitted with cast 307 replacement pistons, stock connecting rods, and a Comp Cams hydraulic roller camshaft.

John’s 306 uses a 350 block, Arias forged pistons, I-beam rods, and a Comp flat tappet camshaft.

Heads for the 316 are 1961 Power Pack castings. They were updated with Comp Cams’ screw-in studs, guideplates, springs, locks, and retainers.

John opened and reshaped the bowls above the valves and blended them into the ports. The valveguides were trimmed to reduce restriction.

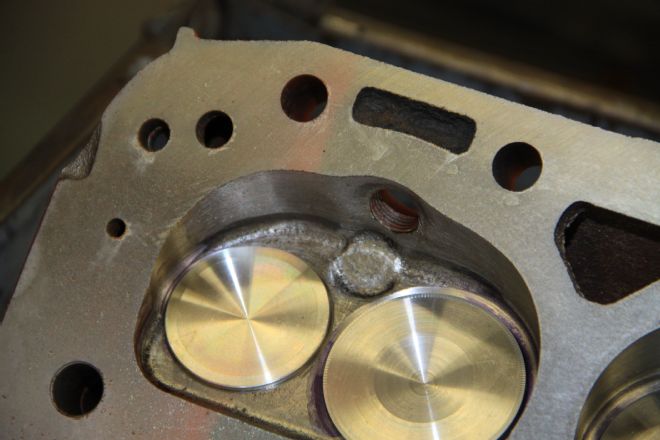

Intake valves are 2.020-inch Federal-Mogul replacements that were cut down to 2.00 inches. Note that the chambers have been opened up around the valves to reduce shrouding.

The exhaust valves are 1.60-inch Federal-Mogul replacements. Again, the chambers have been opened to reduce shrouding.

The 316’s heads were freshened with new, bronze valveguides.

The Comp Cams valve stem seals prevent excessive oil from passing through the guides.

To provide reliable sealing, both engines were equipped with PermaTorque head gaskets from Fel-Pro.

For the 316, we opted for ARP head bolts rather than studs.

All the fasteners on both engines, including the 12-point head bolts, came from ARP. Note that the 316’s heads have been modified for screw-in rocker arm studs.

The 316 heads have the pointed indicator that first appeared in 1956 on dual-quad engines. However, casting numbers are still the most reliable method to identify heads.

Both engines were equipped with Comp Cams Ultra Pro roller rocker arms.

To cope with the pressure of supercharging, the 306 was equipped with ARP head studs.

Valves for the blown engine were 2.02-inch intakes and 1.60-inch exhausts from Comp Cams.

John used cast-iron “camel hump” heads on his blown engine. These were often referred to as “fuelie” heads as they were found on fuel-injected small-blocks, as well as others.

Head modifications on the blown engine were limited to mild porting on the intake and exhaust sides and blending of the bowls.

To go along with the mild porting and bowl work, the heads for the blown engine were treated to screw-in studs, guideplates, and dual valvesprings with dampers, followed by lots of grinding and gloss-black paint to match the block.

As a solid lifter cam was used in the blown engine, lash caps were used on the valve stems to protect them.

Comp Cams tool-steel lifters, pushrods, and rocker arms make up the blown engine’s valvetrain.

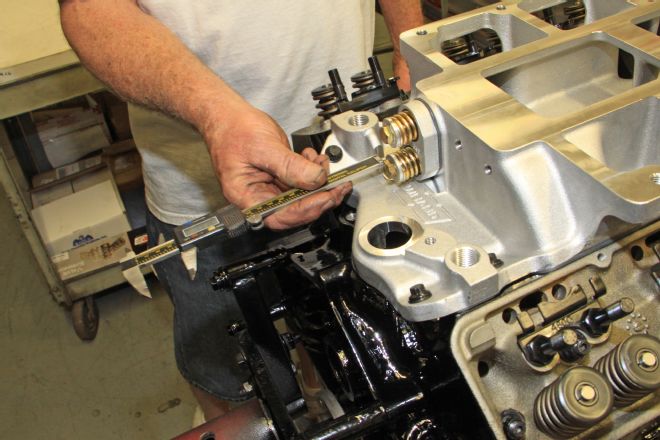

Establishing proper rocker arm geometry is essential. The tip of the rocker should sweep back and forth across the center of the valve stem.

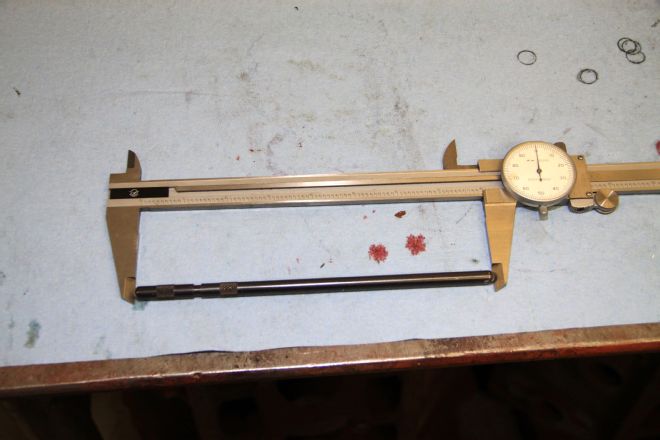

Proper rocker arm geometry can be easily established with these adjustable pushrods from Comp Cams.

John used an adjustable pushrod to establish the required pushrod length for both engines.

Comp Cams offers valvetrain assembly lubricant in a spray can.

Topping off John’s engine is Weiand’s new nostalgia supercharger kit. To keep the old vibe alive, the 1/2-inch toothed drivebelt and pulleys were used.

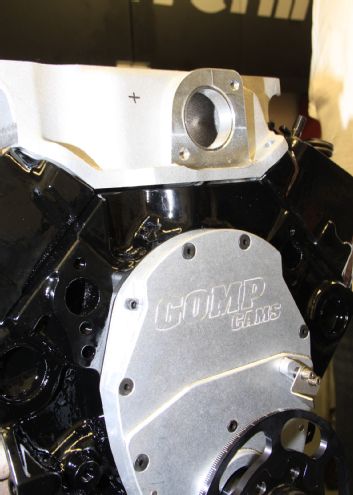

A test-fit of the blower manifold was made to check port alignment and clearance at the block’s front and rear bulkheads.

To seal the gaps between the block and manifold, beads of silicone were applied to the bulkheads.

Several of the ARP bolts that secure the manifold to the heads are under the blower.

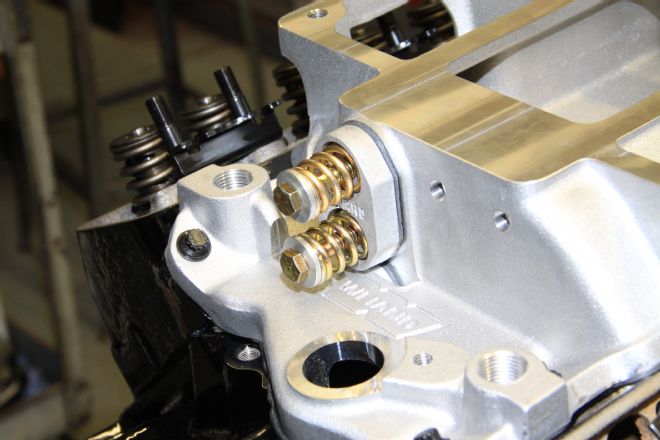

To prevent damage in case of a backfire, there is a pop-off valve in the rear of the Weiand manifold.

The release point of the pop-off valve is established by adjusting the height of the springs to specs.

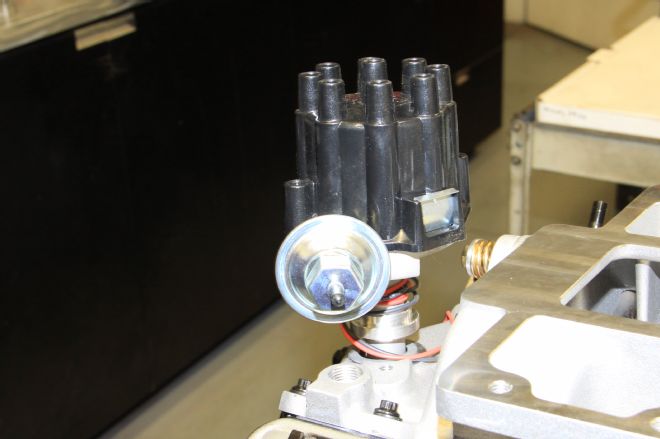

To maintain the nostalgic theme and have all the benefits of contemporary electronics, both engines were equipped with Flame-Thrower distributors from PerTronix.

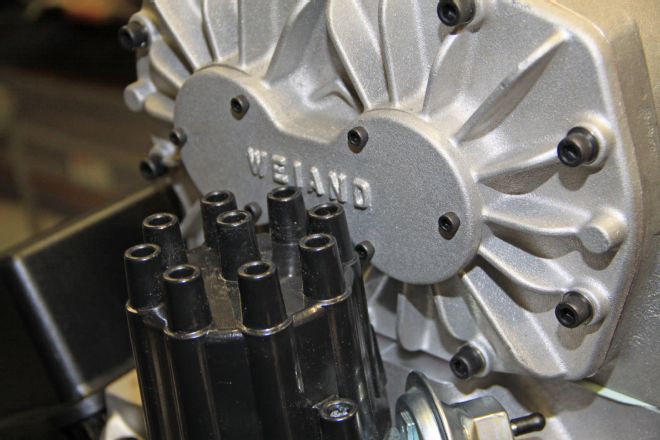

Weiand’s blower case, front snout, and swinging belt adjuster have the vintage look John was after. John fabricated the manifold holding a trio of Holley carburetors.

The finned rear blower cover is another nostalgic touch.

Here, John is mocking up the drive components—the blower will be underdriven 29 percent.

Just for giggles, the new engine now has attached the Southern California Timing Association seal from John’s record-setting Bonneville engine of the same displacement.

Weiand’s new Tri-Power manifold is a medium-rise, dual-plane design that looks right at home on the 316.

Holley’s Tri-Power setup uses a 325-cfm carburetor in the center and a 350-cfm version at each end. The progressive throttle linkage allows cruising on the center carburetor only.

At approximately two-thirds throttle, the outboard carburetors come into play, and all three reach wide open simultaneously.

Included in the Tri-Power kit are beautifully formed steel fuel lines. Note, only the center carburetor has a choke.

The heavy aluminum Comp Cams rocker covers help prevent leaks, and the included internal baffles keep oil from leaking out the breathers.

A black PerTronix distributor cap fits right in with the nostalgia theme of the 316. The Flame-Thrower distributor features a vacuum advance to increase fuel economy under cruise conditions.

The PerTronix Ignitor III system includes an integral rev limiter that is easy to adjust. Note the screw slot and the plus and minus signs with an arrow.

For spark, both engines will rely on PerTronix Flame-Thrower III coils.

John’s engine was run on the dyno with 8 psi of boost on pump gas and through the mufflers that will be on his car.

So there’s no possibility of a cam failure during break-in, John removed the inner valvesprings.

After breaking in the cam, the inner springs were put back in place before making any full dyno pulls.

Our Tri-Power engine was broken in, then several pulls were made. Indications were some jet changes were in order.

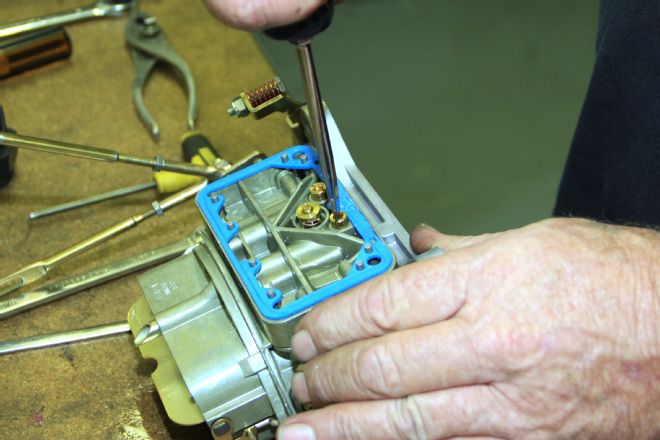

Here’s a cool little trick—John used a cut-off plastic oil bottle to catch the fuel after he removed the bottom screw from the float bowl before the bowl was removed.

The Tri-Power carbs have Holley’s non-stick gaskets and use standard jets and power valves.

After a jetting change, these are the results of the final dyno pull made with the naturally aspirated Tri-Power small-block. Peak output was 338.6 horsepower at 5,600 rpm and 349.7 lb-ft of torque at 3,800 rpm.

The little 306 loved the top end of the tach. Hooked to a four-speed, this will be a fun engine in a lightweight hot rod. Peak output was 419.9 horsepower at 6,600 rpm and 362.1 lb-ft of torque at 5,500 rpm.

Out of curiosity, we compared our Tri-Power engine (dotted line) to a carbureted 5.3L LS (solid line).