It all started with a bench racing session between the author and John Beck of Vintage Hot Rod Design (VHRD). The subject centered on small-block Chevys and the fact that the Gen I versions were now considered by many to be vintage engines. It’s obvious that the improvements Chevrolet has made to the small-block since the introduction of the 265 V-8 in 1955 have made a good engine great; and today, the LS series is the logical choice for anyone building a high-performance engine. But then when hot rodders get together logic is not always part of the conversation. After discussing all the reasons not to do it, the decision was made, it was time to build a pair of classic Chevy V-8s: a triple-carbureted 316 and a blown 306.

John is no stranger to building horsepower. He’s the guy behind a long list of record-holding race engines, including the ground shaker that propelled Dave Davidson over 300 mph on the Bonneville Salt Flats in the less-than aerodynamic VHRD high-boy roadster. Of course, the goals for the engines shown here would be different. Both are destined to be on the street in hot rods where driveability and reliability are important attributes. But the real reason for building these engines was to do something different—admittedly not the most logical basis for decision-making, but again, this is hot rodding.

The foundation for our naturally aspirated engine is a 283 (3.875-inch bore x 3.00-inch stroke). The addition of a 327 crankshaft (3.25-inch stroke) makes it a 307. Our combination uses an additional 0.060-inch overbore (3.935-inches) to bring it out to 316 cubic inches. To get the best combination for the least money, the stock rods were resized, balanced, and equipped with ARP bolts and cast 307 replacement pistons from Federal-Mogul were used. COMP Cams provided the relatively mild XR258HR hydraulic roller ’shaft with 0.480-inch lift on the intake and 0.487-inch on the exhaust, 258 and 264 degrees of duration, respectively, with 110 degrees of lobe separation. Ultimately, the engine will be topped with reworked Power-Pack heads; Holley’s trick, new three-two induction package; and a PerTronix distributor, coil, and plug wires.

For John’s blown small-block, a large-journal 350 block was bored 0.030-inches oversize and now houses a 302 crank ground by Castillo that has been on the shelf for 10 years waiting for a project (the 4.030-inch bore and 3-inch stroke results in 306 cubic inches). Connecting rods are 6-inch Eagles from the D Blown Gas engine that got John into the 200-mph club at Bonneville. They are now attached to a fresh set of forged pistons and rings from Arias. To open the valves in the cast-iron, camel-hump heads, John chose a blower-friendly COMP Cams’ (PN 12-405-5) solid lifter ’shaft with 0.540-inch lift on the intake, 0.563-inch on the exhaust, duration of 255/265 degrees at 0.050-inch lift, respectively, and 114 degrees of lobe separation. Sitting on top of the small-block will be one of Weiand’s vintage 6-71 blowers wearing a trio of Holley two-barrel carburetors.

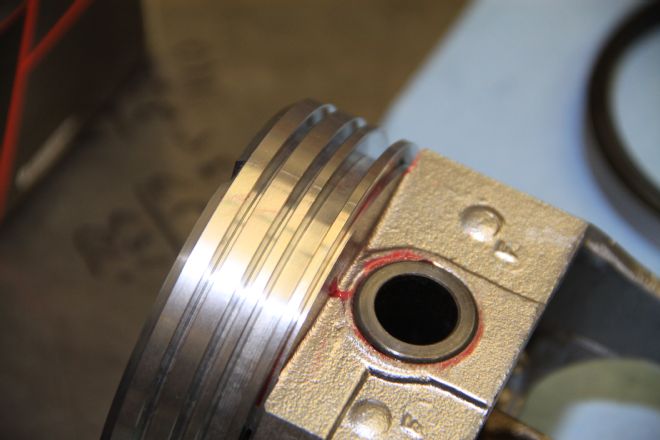

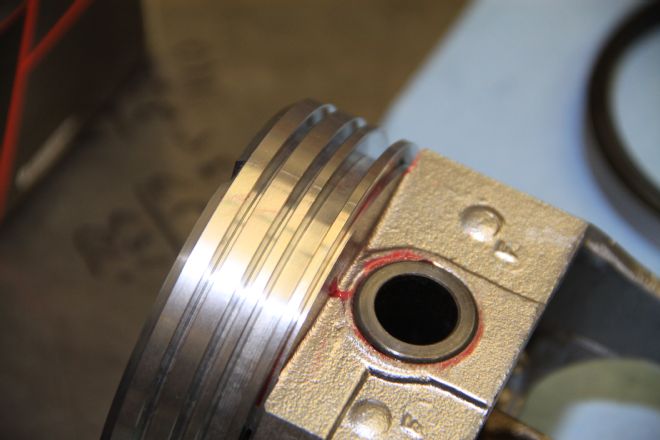

Regarding block preparation, John says, “A naturally aspirated engine needs to have good clearances and round cylinders for a long life; and for good power, it’s even more critical for a blown engine to have these qualities because when things go bad, they go bad quicker.” Admittedly, each machinist/engine builder will have their own ideas on the differences between naturally aspirated and supercharged street engines. In John’s opinion, ring placement on the pistons and ring end gaps are at the top of the list. He adds, “the blown engine will see more heat at the top ring at boost—the more boost, the more heat, and ultimately more horsepower. Most modern piston designs have the top ring moved up to lessen the trapped combustion between the ring and the top of the piston. However, with blower pistons, especially those cut for big valve reliefs, it’s advantageous to move that top ring down away from the valve relief and the heat of combustion because the thin area between the edge of the relief and the ring groove is the area most susceptible to damage.”

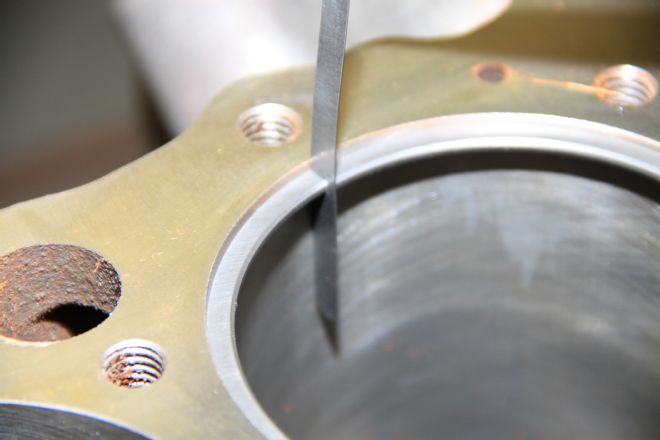

As for ring gap, it’s crucial to have enough of a gap so when the ring expands from high combustion temperatures the ends won’t butt, as the result would be predictably disastrous. For that reason, John’s blown engine has 0.025-inch end gap on the top ring and 0.020-inch on the second, while the naturally aspirated engine has 0.018-inch on the top ring and 0.020-inch on the second.

There are a few other differences in the two short-blocks that we’ll point out as we go along. And in the next installment, we’ll show the final assembly and the dyno results in our Tale of Two Chevys.

John Beck is the man behind this pair of old-school small-blocks. Both were designed and built to rack up lots of miles and be trouble free. We could have made more horsepower with more modern components—but they wouldn’t have been as cool doing it.

Any engine is only as good as its foundation; and it all starts with true main bearing bores. If they’re not right on the money, Bill Hunter cures them with line honing.

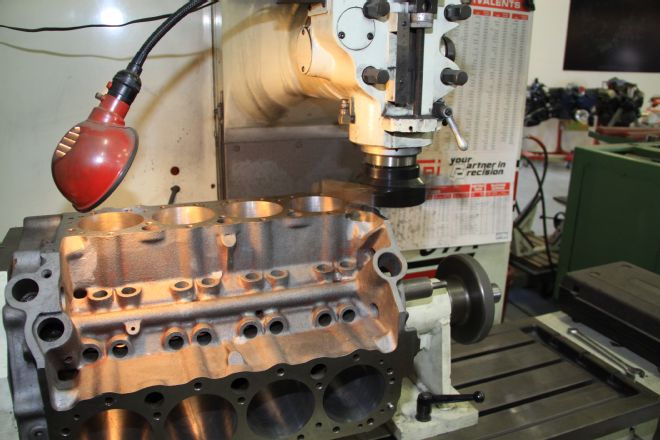

Modern machining equipment allows any discrepancies in a block’s dimensions to be corrected. Here, the cylinders of our 283 block are being bored.

After both blocks were Magnafluxed, the cylinder walls tested for thickness, they then were decked and bored. The final cylinder diameters and finish were established by honing.

The decks of both blocks were cut to make them parallel to the crankshaft and establish the necessary deck height.

During the boring process, the cylinders can be located precisely in relation to the centerline of the crankshaft.

Rod and main bearings came from Speed Pro, a division of Federal-Mogul. The bearing uses a super-duty alloy for extreme fatigue resistance and high-load capacity.

To enhance the strength of the two-bolt bottom end, the 283 block was equipped with ARP studs. Note the oil grooves in the upper main bearings.

The Speed-Pro main bearings are 3/4 grooved, meaning the bottom inserts have short continuation grooves to enhance crankshaft lubrication.

Standard Fel-Pro silicone rear main seals are blue or black. The high-performance red seals are made from Viton to withstand higher temperatures (although they are less forgiving of runout and crankshaft movement).

Paul Grindstaff supplied the 327 crankshaft that was Magnafluxed and turned 0.010-inch undersize on the rod and main journals. Fortunately, our 283 block accepted the larger 327 counterweights without any grinding.

Crankshaft endplay on both engines was in the standard 0.003-0.005–inch range.

The four-bolt block for the blown engine was also equipped with ARP studs—they featured extended, smaller-diameter threaded ends to mount a windage tray.

This is what happens when a 283 piston, a 5.7-inch rod, and a 327 crankshaft are combined—the pistons pop out of the block. The correct piston for this combination is a standard replacement for a 307. It has the piston pin located closer to the top of the piston.

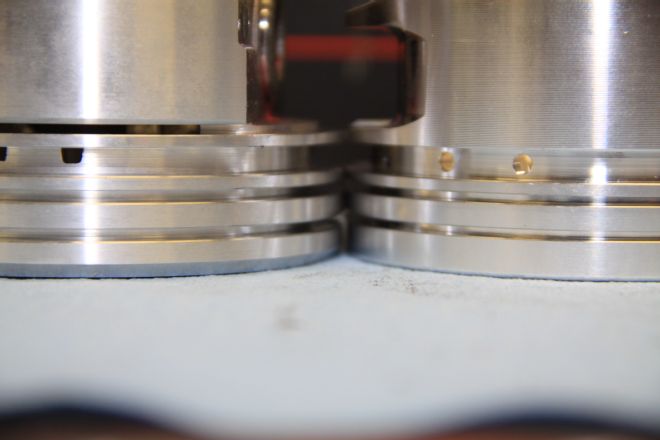

On the left is a standard, cast replacement piston for a 307 used in the naturally aspirated engine; specified cylinder wall clearance is 0.0015-inch. On the right is an Arias forged piston for the blown engine that uses a looser fit; in this case, clearance is 0.0055-inch.

On the left is a naturally aspirated piston and on the right is a blower piston, with the top ring positioned farther from the crown.

Salvaged from a race engine, the H-beam rods for the blown engine were rebushed, resized, balanced, and equipped with ARP bolts.

Standard ring gaps were used for the naturally aspirated engine and they were opened up for the blown version.

An Arias forged piston with the rings and rod installed. To reduce friction, the wristpins are full floaters that pivot in the rod and piston.

The full-floating wristpins in the Arias pistons are retained with spiral lock.

By contrast, the 307 pistons use wristpins pressed into the stock rods.

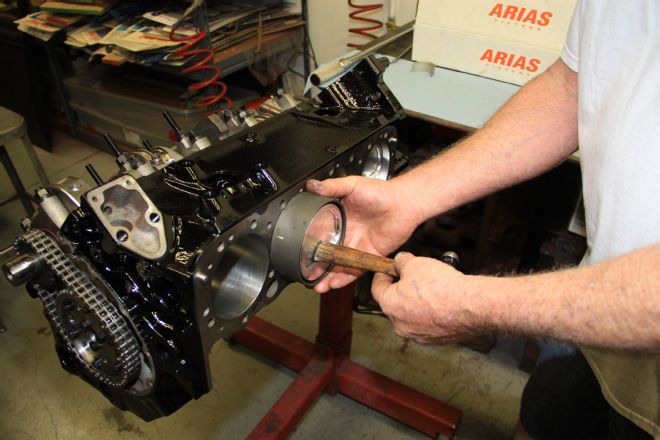

Before the pistons were installed, the skirts were coated with assembly lube.

Using a tapered piston ring compressor, the pistons were carefully pushed into the block.

To ensure proper torque values were established, the cap screws for the rods were doused with ARP lubricant.

As a means to reduce internal friction and provide a more favorable cam profile for the naturally aspirated engine, we opted for a hydraulic roller cam from COMP.

The retrofit roller lifters use tie bars to keep them aligned with the cam lobes.

For the blown engine, John chose COMP Cams’ tool steel solid lifters.

To make sure the cam timing of both engines was spot on, John degreed both cams.

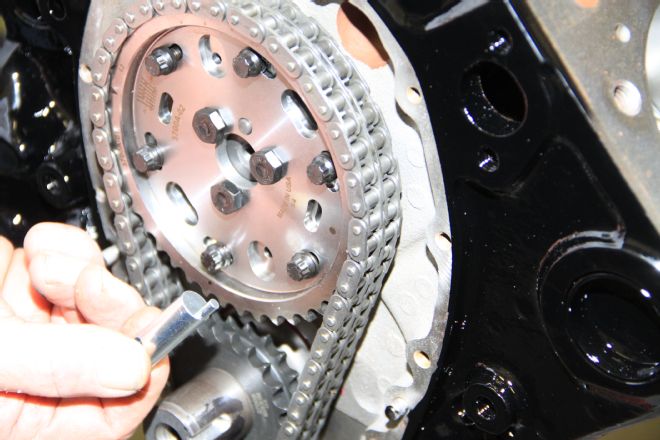

When degreeing a cam, optimizing its position is simple with COMP Cams’ trick adjustable timing set. Note the degree marks and pointer.

This tool is used to adjust the cam sprocket on the hub. Once adjusted, the sprocket is locked in place by the six screws. This is certainly easier and more accurate than using offset bushings.

To control cam thrust, COMP offers Teflon thrust buttons. They can be trimmed to provide the proper endplay.

Another option for establishing camshaft endplay is this thrust button with a bearing and changeable shims.

Here, the steel thrust button has been installed in the cam sprocket.

With the cam degreed and the thrust button installed, the adapter ring for COMP’s quick-change timing cover was installed.

Along with providing access to the cam and timing components without disturbing the oil pan, the COMP Cams cover has a port to allow checking camshaft endplay.

The bottom end of the blown engine is equipped with a windage tray. Both engines use high-volume, standard-pressure oil pumps from Sealed Power.

Advisable for a blown engine, John machined the crank snout for an additional 1/4-inch key.

Rather than a damper, John used a steel crankshaft hub for strength and reliability.

For a damper on our naturally aspirated engine, we used a Rattler from TCI Automotive; it’s SFI-approved and degreed to make timing easy.

The unique design of the Rattler features steel rollers (centrifugal pendulums) that roll forward during the compression stroke and backward during the power stroke to keep engine speed variation and vibration to a minimum. The rollers are said to actually store and release energy back into the crankshaft rather than converting it to heat energy as dampers do.

For the blown engine, John used a rare Corvette 5-quart pan with baffles and trap doors around the oil pump pickup. Here, the depth of the pan is being measured to establish the location of the pickup.

With the measurements from the pan, John located the pickup to be roughly 3/8-inch off the bottom of the pan.

John has a unique method of securing the pickup screen to the pump; he drills and taps the inlet tube for a set screw.

As we will be using the original road draft tube location for a PCV valve, we kept the original breather canister in the valley of the 283.

Before the lifters were installed in the block of the blown engine, COMP Cams’ high-ZZDP oil was poured over the cam.

The blown 302 was equipped with ARP head studs and the carbureted 316 will use ARP cap screws.

With the pistons in place, deck height was measured. The 316 measured 0.005-inch down in the holes and the 306 was 0.007-inch.