In this modern era of mega-inch big blocks and LS-swapped-everythings, it’s easy to overlook the value of one of the most versatile engines ever designed. I speak, of course, of the gen-I, small-block Chevy. There have been over 100 million small-blocks produced, and they are quite possibly the only engines cheaper to buy new than to rebuild.

That got us thinking, which is never a good thing. A cursory search on Summit Racing found that a Chevrolet Performance 195-horse crate engine sets you back an entirely manageable $1,459.99 for a complete long-block, sans intake manifold and front accessories. Could you build an engine for less than that? Not if it needs any machine work. By the time a core engine leaves the machine shop with a basic hot tank, and bore/hone, the bottom line is already racing toward $1500 (including the price of the core engine). Add the price of gaskets, bearings, a crank that needs turning, and heads in need of a valve job and you’ve easily eclipsed the price of a crate long block.

As power-mongering hot rodders, a-buck-ninety is not enough ponies to get any of our hearts pumping. But, with a static compression ratio of 8.5:1, the little 195-horse crate is begging for boost.

So, to test our theory and bring our visions of budget boost to life, a call was placed to Summit Racing for 195-horse crate engine to serve as our lab rat and to Weiand for an example of their 142 Pro Street roots-type supercharger – one of the most affordable blowers on the market.

The Premise

A sum of $3,635 bought us the longblock, and supercharger kit, but as astute readers will notice, there are more components necessary than that to run a motor. The 195-horse crate does not come with a harmonic balancer, oil filter adapter, dipstick, ignition or induction. But hear us out before you cry budget foul!

Over the years, we’ve seen so many muscle cars cruise into a car show/event dripping oil and trailing smoke from a tired and well-traveled small-block. Heck, we’ve often been the guy behind the wheel of one of those cars. Once the hood is popped, however, that well-worn motor is topped with a shiny new intake manifold, a 4-barrel carb, headers, and an aftermarket ignition.

These modifications are by far the easiest and most affordable to make and, as such are usually the first performance additions to any engine. A full engine build, with its additional cost incurrence, is always a goal placed much later down the road. Often set aside for when the original mill bites the dust, or after the prolific cloud of black smoke from the tailpipe begins to attract police attention.

So, it is with this concept in mind that we propose the budget blower motor as an alternative to an engine build, for the smallblock already under your hood. In this common situation, all of the missing components such as the distributor, balancer and front accessories can be recycled. Even the carb can be easily modified to work in harmony with the blower.

The Specimen

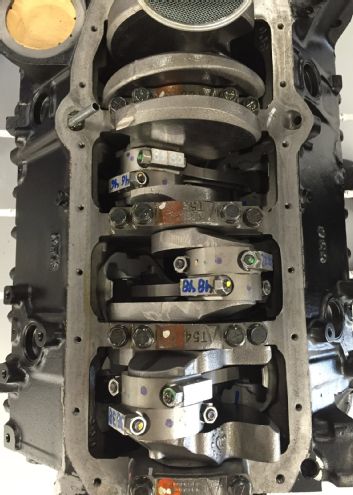

What promptly arrived at our Santa Ana, CA headquarters in a wooden crate from Summit Racing is, in many ways, the same small-block you’ve seen time and time again. However, there are few exceptions. When we popped the oil pan off to verify the small-block had the promised 4-bolt mains, what we found was a set of LT1-sourced, powder-forged rods. These are stout pieces that have proven to survive at horsepower levels, far in excess of what we had planned. Also, the 4-bolt main caps (which were indeed present) make the block an excellent candidate for a stroker build later down the line.

We mounted the engine on a stand and got to work bolting on the necessities from our old donor motor. A used balancer was hung on the front of the motor and a set of spark plugs with a blower-friendly heat range were installed. We also took this time to bolt on the oil filter adapter, tap in a dipstick tube on one side, and plug the dipstick tube on the opposite side (this block has both for driver or passenger side dipsticks).

We mocked up the Weiand Pro Street 142 blower, which retails for $2175.95, to make sure everything fit with our combination and all was well. The kit includes gaskets, pulleys, a blower manifold and a belt – everything we needed to turn our wheezy workhorse into a powerhouse.

We packed our blower back up and loaded the crate engine into staffer, Steve Rupp’s, pickup and headed down to Westech Performance to see what our cheapo crate could do on the engine dyno.

1. The Chevrolet Performance 195-horse engine isn’t one of those fancy free-range small-blocks. It promptly showed up from summit racing in this … crate – hence the name.

2. For what we got, the Chevrolet Performance 195-horse crate engine is hard to beat. The all-new internals are supplemented by some modern improvements and the 8.5:1 compression ratio was just begging for boost.

3. We grabbed a balancer off our core motor and installed it on the nose of the crank. Later, we decided to switch to a Summit Racing 2-piece timing cover to make swapping cams easier on the dyno. If you aren’t changing cams regularly, the stock cover is a good, thick stamping.

4. As promised, our $1,459.99 motor came with 4-bolt mains. This makes it a stout platform from the get-go, but an even better block for a stroker build later down the line.

5. We ran an 1/8-inch pipe tap through our extra dip stick hole and added a plug. Another option is to tap in an 1/8-inch expansion plug.

6. We were surprised to see an LT1-powder forged connecting rod when we pulled the pan. These rods are far better than the old, ‘pink rods’ and have proven themselves time and time again to be reliable pieces.

7. Before bolting our Weiand blower intake onto the engine, we drilled and tapped the back of it for an additional vacuum/boost port. The manifold has only one port and since we planned for a vacuum advance, boost reference to a carb, and a boost gauge, we thought it wise to add one more port.

8. The Weiand 142 Pro Street blower’s case is compact and easily leaves enough room to mount a bulky HEI distributor. We connected the vacuum advance to the manifold below the blower (not shown). This allows the engine to have adequate spark advance at part throttle cruise (no boost) for better economy. When the blower begins to produce boost, the vacuum advance will immediately retard, keeping the engine from knocking.

9. Another item that needs to be installed on the crate engine is an oil filter adapter. Again, we grabbed one from a core engine.

10. We boxed all of our parts up and headed down to Westech to put the engine through the ringer. The first step was to fill it up with Lucas SAE 30 break in oil.

11. This sight window is the means to make sure your blower is adequately lubricated. Ours came with a factory fill of oil.

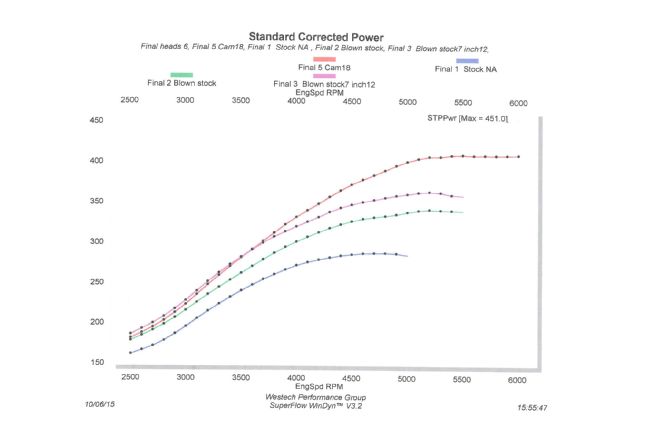

12. Before bolting on the blower, we decided to see what our 195-horse crate ‘really’ made on the engine dyno. With a borrowed Edelbrock Air Gap intake, Holley 650 carb, and 1.75-inch headers, the engine put down an entirely unexpected 287 horsepower. If it was setup with a restrictive iron intake and stock cast-iron manifolds, the output would have likely been much closer to the sickly 195-horse rating.

13. With our NA numbers logged, the Weiand 142 blower was set onto the engine. We were really excited to see what the blower would do on the stock long-block with its low compression and tiny cam. The result was 341 horsepower and 397 lb/ft of torque.

14. Our fuel metering device for the tests was a 750cfm Holley blower carb. The blower carb has a 50cc accelerator pump (which would likely be a little much for our small-displacement engine and tiny blower on the street) Check out www.superchevy.com for our story on how to convert any Holley 4150-4160 carb to blower spec.

15. We swapped to this 2.5-inch upper pulley, which brought our blower ratio to 2.40:1. That means the blower spun 2.4 times faster than the engine, bringing our boost from 6.1 psi to 10 psi. The end result was a bump in output to 363 horsepower and 425 lb/ft. Wile we picked up more power, it was clear the tiny cam was holding the combination back.

16. A Comp Cams hydraulic flat tappet blower grind was selected to maximize our budget blower combo. Duration of the cam spec’d in at 218/230 (at .050) and the LSA was a wide 113. The conservative duration numbers let the engine breath better than before but will work with a stock converter, allow for power brakes, and maximize low speed torque production.

17. Because this was a flat tappet grind, we made sure to install new lifters to match the camshaft. The lifters, valve springs, retainers, locks, and timing chain were included in our Comp Cams K-kit (K-12-556-4) to supplement the new camshaft. The decision to stay with a flat tappet grind was entirely budget oriented.

18. To ensure the new lifters were filled with oil, Westech’s Steve Brule’ primed the engine’s oil system.

19. Another perk of the 195-horse crate is that positive valve seals are installed at the factory.

20. We swapped the valve springs out while on the engine dyno. The springs are soft enough that the cam can be broken in on them, yet stiff enough to control the valves up until our 6,000 rpm redline.

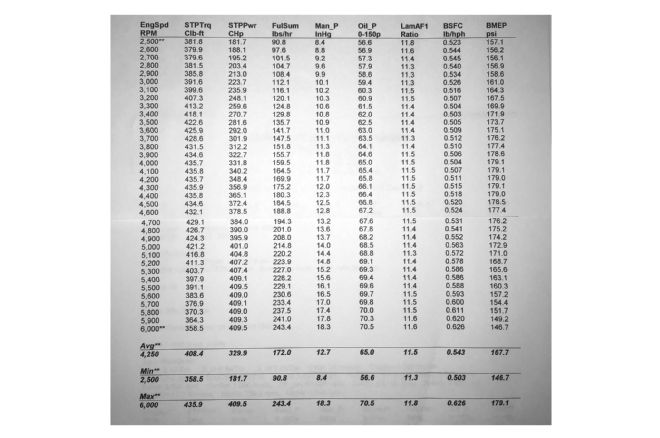

21. After breaking the cam in, we made our final pull of the day. With the blower cam installed in the block and the 2.5-inch blower pulley still installed on the Weiand Blower, the engine churned out 409 horsepower and 435 lb/ft of torque. Better yet, look at the torque throughout the rpm range. There is 381 lb/ft ready and waiting at only 2,500 rpm and the average torque across the rev range is a stump pulling 408 lb/ft!

22. Here is a dyno plot of each test we performed on the motor. It is easy to see how much the blower helped the engine to perform better by leaps and bounds. The red line represents the camshaft swap, which again hugely bolstered performance. At the end of the day, this engine set us back only $3,979.91, idles great, and makes stupid torque. We’d have to say it would peg the fun-meter in any Bow Tie ride.

Test 1: 195-Horse Crate Baseline Run ($1,459.95)

The Chevrolet Performance 195-horse crate engine is, undeniably, the workhorse of the crate engine world. And, while its diminutive output rating has won it little acclaim, what we found on the dyno was more than a little surprising. We borrowed an Edelbrock Air Gap intake and Holley 650 carb from Westech and used an HEI distributor from our old mill to run the engine in a naturally aspirated, out-of-the-crate condition. The little mouse surprised us with peak power and torque numbers of 287 and 361.7 respectively, nearly 100 horsepower more than it is rated at. So what’s the deal? No, there is no dyno sorcery at work here. The power rating the engine carries is extremely generic, and assumes the worst-case scenario of induction and exhaust. In this situation, since we weren’t rocking a 2-barrel TBI intake manifold and extremely restrictive cast exhaust manifolds, the engine was free to breathe and ready to prove its worth. At this point we had only the cost of the engine ($1,459.99) into the build as we borrowed all of the missing components from a core motor and the intake and carb from Westech.

Test 2: 195-horse Crate + Weiand Pro Street 142 Supercharger

With a stated compression ratio of only 8.5:1, this engine was practically built for boost. With that in mind, we eagerly bolted our Weiand Pro Street 142 blower onto the mouse and let it rip on the stock shortblock. The result was healthy 341 horsepower and 397.2 lb/ft of torque with a boost pressure of only 6 psi. Torque swelled right off idle with 375 lb/ft readily available at only 2500 rpm! If a little boost is good, a lot of boost is even better, right? To that effect we swapped the blower pulley from the standard 3.05-inch unit to a smaller 2.5-inch unit. This gave us an overdrive ratio of 2.4:1 and would allow us to rev the motor up to a theoretical 5,800 rpm without eclipsing the blower’s 14,000 rpm limit. The smaller pulley and increased blower speed brought an additional 4 psi of boost to the table for a total of 10 psi. Horsepower rose to 363 while torque jumped to 425 lb/ft.

Test 3: 195-Horse Crate + Weiand Pro Street 142 Supercharger+ Blower Cam ($3,979.91)

With the blower’s rpm potential already tapped, we felt that we had hit a wall with the engine’s completely stock innards. The anemic camshaft was holding up airflow and limiting power. The next step was to replace the wimpy bump-stick for something with enough lift and duration to feed the engine’s voracious appetite for boost. We spent a lot of timing choosing the right camshaft for this application.

Rather than going straight for the biggest and baddest solid roller cam on the shelf. We opted to use a Comp Cams hydraulic flat tappet grind with fairly humble specs. The intake spec’d in at a conservative 218 degrees intake and 230 degrees exhaust (measured at .050-inches of lift) and had a blower friendly 113 degree LSA. Lift is a conservative .462-inches on the intake and .480 on the exhaust. Better yet, the cam was available in a K-kit that included springs, retainers, locks, valve springs, and the cam and lifters for $343.97 – a price befitting of our low-buck theme.

After swapping in the new cam and running though a break-in cycle to properly mate the fresh lifters, we pulled the motor on the dyno. With the new cam and the smaller pulleys from the last test, we were rewarded with 409 horsepower and 435 lb/ft of torque, a huge gain of 46 horsepower from a simple cam swap! We also observed the boost pressure drop from the previous 10 psi to 9psi as more air found its way out of the intake and into the cylinder where it was turned into horsepower.

While there’s no doubt there is more power available with a bigger cam, the conservative valve timing and wide LSA allowed the engine to idle smoothly at 600 rpm, produce 16 inches of manifold vacuum (enough to run power brakes) and average 408 lb/ft of torque through the pull.

Conclusion: Who Says Blower Motors Have to Break the Bank?

At the end of the day we turned a pretty humble package of parts into a mean blower motor that has the look, the sound and the tire-shredding torque to back it all up. Best of all, it’s civil enough to power anything from a daily driver to a street/strip stormer. In the next issue we’ll subject our motor, which we’ve dubbed project Blown Budget, to a few more low-buck upgrades to up the power ante and continue testing the durability of the stock bottom end. It is important to note that we pulled our Chevrolet Performance 195-horse crate engine 25 times on the dyno during testing with zero durability issues. Say what you will about the cheap, little, crate, but it’s a tough little rodent.