The Combo

Federal Heights, Colorado’s Greg Dietrich purchased a 1992 Chevrolet Silverado 1500 with a carbureted 502hp ZZ502 big-block crate motor, a 4L60E automatic overdrive trans with a 2,600-rpm stall-speed converter, and 4:10:1 gears out back. He had a local shop convert the engine to electronic-port fuel injection using a BigStuff3 electronic fuel-injection (EFI) engine-management system.

When he’s not at the drags, Greg Dietrich cruises with his buddies in the The Sabers of Denver car club.

When he’s not at the drags, Greg Dietrich cruises with his buddies in the The Sabers of Denver car club.

The Problem

From Day 1, Greg says he had to “crank it forever” to get the truck started. When it finally did fire and run, the motor “would overheat before you could get anywhere. The engine would pop and bang going down the road. It felt like the injectors weren’t firing. It was undriveable. Worse, my wife wouldn’t put up with it.

Unfortunately, with EFI the motor proved nearly impossible to start. When it did run, it drove terribly and overheated. No one could fix it.

Unfortunately, with EFI the motor proved nearly impossible to start. When it did run, it drove terribly and overheated. No one could fix it.

“I had two other local tuners try to fix it by changing the fuel and ignition values in the calibration, but they just made it worse. One place even sold me a new camshaft, claiming the crate motor’s relatively mild GM hydraulic roller wasn’t a good fit for EFI” (even though GM sells a complete EFI Ram Jet 502 with the same cam).

Now $2,500 lighter in the wallet, Greg finally bit the bullet and asked his brother, Allen, and nephew, Joshua, to help him get the truck on the road. The father and son team own J & A Automotive, a Westminster, Colorado, shop that performs everything from general repairs on stockers to custom hot rod builds. Although the Dietrichs had never dialed-in an aftermarket fuel-injection system, they were willing to learn. BigStuff3 suggested Mike Moran’s Moran Motorsport as a go-to tuner source. Thing is, Moran is based in Taylor, Michigan, and 1,250 miles is kind of a long commute by anyone’s standards. But in this brave new interconnected world, it’s nothing that a telephone and a laptop can’t solve.

The Rescuer

Mike Moran has been successful in the automotive performance business his entire life, but he’s constantly upping the ante, improving his game. He started up building and driving some of the most impressive Fastest Street Car drag-racing machines in the country. Today, many consider his proprietary big-horsepower fuel injectors the best high-flow units in the industry. Besides continuing to build high-power, fuel-injected street and racing engines, Mike is also one of the most sought-after “remote” EFI tuners in the country (if not the world).

Have telephone, will tune: Working through phone and Internet, Mike Moran offers BigStuff3 tuning services worldwide.

Have telephone, will tune: Working through phone and Internet, Mike Moran offers BigStuff3 tuning services worldwide.

Mike’s particular focus is on tuning cars running John Meaney’s BigStuff3 EFI systems. You’ll often find Mike up late at night in front of his two huge monitors, talking and tuning with customers around the world. He’s tuned drag cars in Australia, dialed up and tuned a sandrail in the desert of Dubai, then tuned a Pro Mod racer in Sweden—all in a matter of hours. Says Mike, “The future is here. I can tune these vehicles from just about anywhere today. The speed of Internet connections is now good enough in most places. It really is incredible.”

With a remote connection established over the Internet to a laptop connected to the BigStuff3 controller, Mike dialed-in Greg’s Rat motor.

With a remote connection established over the Internet to a laptop connected to the BigStuff3 controller, Mike dialed-in Greg’s Rat motor.

The Special “Tools”

Remote tuning requires an Internet connection and a Windows-based PC laptop, preferably with an old-school serial port. If you don’t already have a PC with a serial port like Josh does, Mike offers two solutions:

USB-to-serial port adapter cable: Because of interface issues, it’s difficult to find a reliable and consistent adapter. Mike says Radio Shack’s Gigaware-brand adapter (PN 2603487, $19.99) seems to work pretty well. This 6-foot USB-to-DB9 RS232 serial adapter cable is also available directly through Moran.

Refurbished PC with a serial port: “You can still buy reconditioned Windows XP computers for $150. I stock them and sell to customers whenever they can’t seem to make their setup work.”

Greg’s family is heavily into cars. Nephew Joshua and brother Allen own J & A Automotive, a full-service, Denver-area auto repair facility. Josh followed Mike’s verbal phone instructions to initially eliminate some sensor and wiring glitches, then let Mike takeover his local laptop to input calibration updates. Precisely following instructions is critical to expediting the process.

Greg’s family is heavily into cars. Nephew Joshua and brother Allen own J & A Automotive, a full-service, Denver-area auto repair facility. Josh followed Mike’s verbal phone instructions to initially eliminate some sensor and wiring glitches, then let Mike takeover his local laptop to input calibration updates. Precisely following instructions is critical to expediting the process.

If all this sounds ancient—it is. But Mike says a modern solution is in the pipeline, at least for the BigStuff3 system. As early as this summer, you may be able to connect wirelessly to the BigStuff3 controller without the need for an interface cable. Potentially, this could allow connection via a smartphone as well. What’s holding things up is resolving potential wireless security issues.

At present an older PC that retains a 9-pin serial port remains the preferred solution for remote tuning connectivity. Fortunately, Josh had an old XP-based laptop lying around, plus his shop has wi-fi. “We hooked my computer up to the Internet via that and installed BigStuff3’s serial-port cable between the controller and my computer.”

At present an older PC that retains a 9-pin serial port remains the preferred solution for remote tuning connectivity. Fortunately, Josh had an old XP-based laptop lying around, plus his shop has wi-fi. “We hooked my computer up to the Internet via that and installed BigStuff3’s serial-port cable between the controller and my computer.”

Modern-day PCs come with USB ports instead of serial ports; according to Mike, the very speed of today’s USB protocols can introduce too much background noise—so it’s hard to find a USB-to-serial cable adapter that’s reliable. Mike says he’s had good luck with this Radio Shack Gigabyte unit (PN 26-949, replaced by PN 2603487).

Modern-day PCs come with USB ports instead of serial ports; according to Mike, the very speed of today’s USB protocols can introduce too much background noise—so it’s hard to find a USB-to-serial cable adapter that’s reliable. Mike says he’s had good luck with this Radio Shack Gigabyte unit (PN 26-949, replaced by PN 2603487).

Next, you’ll need a remote-assistance plug-in. Later versions of Windows have a simple assistance program built into the OS, but Mike still prefers more robust third-party solutions, either TeamViewer or GoToAssist. Free for the user being supported, both work with all versions of Windows and even with Macs. The remote tech (in this case, Mike) simply generates a web-link plus a code number for the remote-support recipient to enter. A small script then downloads, allowing Mike to temporarily control the user’s computer.

Mike believes the BigStuff3 engine-management system is the highest-tech, lowest-price EFI system out there. “It has the tech of an IndyCar system with the price of an entry-level system,” he says. With correctly functioning sensors and proper inputs entered into its initial setup screens, it usually can construct a decent baseline curve to at least get you up and running.

Mike believes the BigStuff3 engine-management system is the highest-tech, lowest-price EFI system out there. “It has the tech of an IndyCar system with the price of an entry-level system,” he says. With correctly functioning sensors and proper inputs entered into its initial setup screens, it usually can construct a decent baseline curve to at least get you up and running.

The Initial Diagnosis

The Rescue began with a phone conversation between Joshua and Mike. “When I got on the phone,” Mike says, “the first thing we did was run down all the particulars of the engine and vehicle: cubic inches, camshaft, headers, maximum rpm, transmission, rearend gearing, vehicle weight, intended vehicle usage. I use all this info to build a starting point calibration that we can flash into the BigStuff3.” During the initial phone call, Josh says, “Mike gave us some homework: Make sure all electrical connectors were fully mated, get the right injector rating, and determine the amount of crank degrees BTDC the ignition was firing at with a timing light.”

Mike says different distributor models may need different amounts of base timing to perform effectively with the BigStuff3. Greg’s truck was running a DUI-supplied, large-cap HEI distributor.

Mike says different distributor models may need different amounts of base timing to perform effectively with the BigStuff3. Greg’s truck was running a DUI-supplied, large-cap HEI distributor.

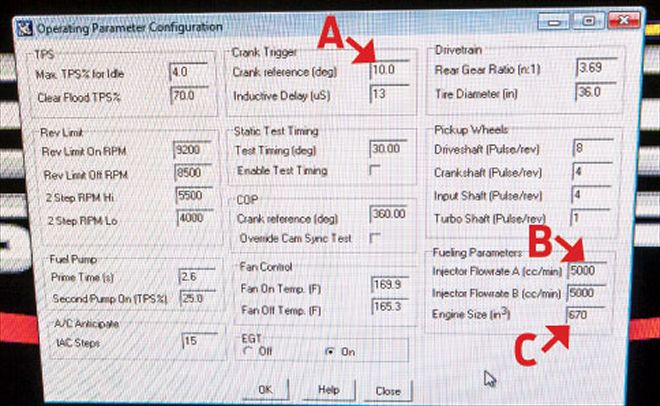

It turns out the truck’s base timing had been incorrectly set to the industry-standard value of 45 degrees BTDC, but a noncomputer HEI like Greg’s unit wants the physical timing at 6 degrees BTDC on the balancer. You must also enter the proper base timing value on the BigStuff3’s system’s software configuration page.

It turns out the truck’s base timing had been incorrectly set to the industry-standard value of 45 degrees BTDC, but a noncomputer HEI like Greg’s unit wants the physical timing at 6 degrees BTDC on the balancer. You must also enter the proper base timing value on the BigStuff3’s system’s software configuration page.

The Fix: Injectors and Fuel Pressure

“One of the pieces of info that Josh didn’t have was the injector size,” Mike explains. “This is critical to getting the EFI calibration set-up properly. I had him remove one of the injectors and take cellphone pictures of it, and any visible part numbers or indicators, so I could figure out their size.”

Based on J & A’s supplied injector info, Mike determined the installed units were “about 20 pounds smaller than what the owners thought was in the car: The injector size had been entered into the software program as 65-lb/hr units, but they were really 43 lb/hr.”

This is one of the main configuration pages on the BigStuff3 that needs information on the engine. Here, the right values for base timing (6 degrees, A), injector flow-rate (452 cc, B), and engine size (502 ci, C) still need correction.

This is one of the main configuration pages on the BigStuff3 that needs information on the engine. Here, the right values for base timing (6 degrees, A), injector flow-rate (452 cc, B), and engine size (502 ci, C) still need correction.

Ideally, Mike prefers a 50–75 percent injector duty cycle, although in a pinch you can skate by with up to 80 percent (100 percent means the injectors never shut off). “Once you get over 80 percent, the injector’s long-term durability decreases and the real-world flow increase tapers off.” Eight 43-lb/hr injectors can support around 516 hp at the industry-standard 43.5-psi fuel pressure, 75 percent duty cycle, and slightly rich 0.5 brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) value—so they were adequate for Greg’s 502hp-rated GM 502 crate engine:

(43 lb/hr × 0.75 duty cycle × 8 injectors) ÷ 0.5 BSFC = 516 hp

The injector’s theoretical 100 percent 43 lb/hr flow rating must be converted to cc/min for entry into the BigStuff’s software setup menu by multiplying by 10.5 to yield 452 cc/min.

43 lb/hr × 10.5 = 451.5 ≈ 452 cc/min

If that’s sounds too complicated, Mike says you can get “close enough” by simply adding a “0” to the end of the whole-number “43”—so 43 becomes 430.

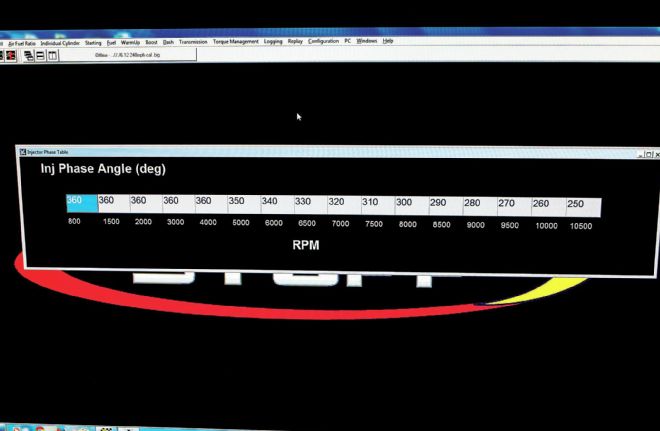

The injector phasing-angle is their firing point in degrees ATDC on the induction stroke, as based on intended use, injector size and duty cycle, intake runner length and injector position, cam, and engine rpm. This table lets you vary the base phase setting versus rpm. Mike prefers 340–360 degrees for a street engine and 250-degree phasing on race engines—more fuel/larger injectors and higher rpm require an earlier firing point.

The injector phasing-angle is their firing point in degrees ATDC on the induction stroke, as based on intended use, injector size and duty cycle, intake runner length and injector position, cam, and engine rpm. This table lets you vary the base phase setting versus rpm. Mike prefers 340–360 degrees for a street engine and 250-degree phasing on race engines—more fuel/larger injectors and higher rpm require an earlier firing point.

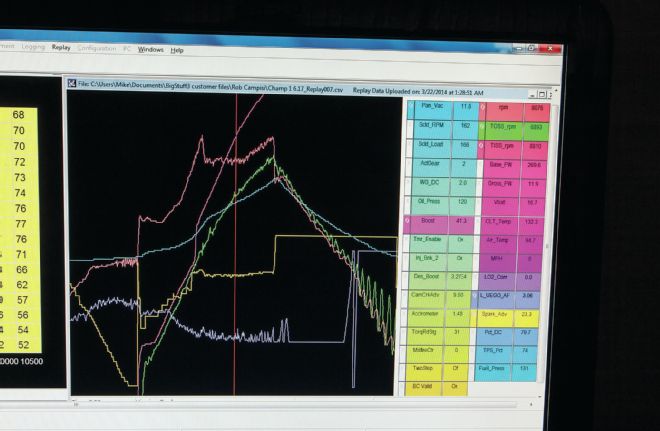

This is the basic BigStuff3 system monitoring screen. Once the engine is running, these readouts let Mike read critical engine and sensor output data, permitting him to quickly identify any anomalies.

This is the basic BigStuff3 system monitoring screen. Once the engine is running, these readouts let Mike read critical engine and sensor output data, permitting him to quickly identify any anomalies.

Mike also had Joshua check that the base fuel pressure was set to BigStuff’s recommended 43.5-psi operating pressure, both physically at the fuel regulator and on the software’s calibration screen.

The Fix: Base Timing

“Once we had the fuel set up,” continues Mike, “I moved on to getting the initial ignition timing set. All EFI systems assume the physical position of the initial or ‘base’ ignition timing, but people often don’t have this set correctly.” A big-cap HEI like Greg’s distributor requires a 6-degree BTDC base-timing setting, but his system was set up to the industry’s “default” 45-degree standard. Getting the timing right is a big deal: with the wrong injector size and wrong timing, it was a miracle the truck ran at all.

BigStuff3 Base Timing Distributor Timing Industry Standard 45° Ford Thick-Film 10° GM HEI 6° MSD Billet 45°

Josh was pleasantly surprised the timing issue was so easily resolved. “With the sequential BigStuff3 EFI management system, a previous tuner told me we would have to add a crankshaft position sensor, but it turned out we didn’t need it.” Mike explains that while the distributor doesn’t have the resolution provided by a discrete crankshaft sensor, “The eight reluctor points on the HEI’s trigger wheel are sufficient through 700 hp. [At more than 700 hp], ignition and valvetrain noise, a typical solidly mounted engine, and slop in the cam gear generate too much static and background noise, making a separate crankshaft position sensor-wheel mandatory.”

But as a sequential system, isn’t a camshaft position sensor (CPS) also needed? “Ideally, yes. But at the 500hp level, you can get by with less-than-optimum fuel-injector timing.” If desired, some versions of MSD billet distributors have dual pickups, one of which can be used for a CPS.

The IAT is installed in the bottom of the air-cleaner base. When Big Stuff’s software reported wacky IAT sensor readings compared to the known real-world ambient temperature conditions, Mike had Josh remove the air cleaner to inspect the IAT.

The IAT is installed in the bottom of the air-cleaner base. When Big Stuff’s software reported wacky IAT sensor readings compared to the known real-world ambient temperature conditions, Mike had Josh remove the air cleaner to inspect the IAT.

The Fix: MAP Sensor

Mike noticed the BigStuff3 software’s “dashboard” screen was reporting an impossible out-of-range reading for a normally aspirated engine, indicative of either the wrong manifold absolute pressure (MAP) sensor for the application or the wrong sensor information was entered into the initial calibration screen. In this case, it was a data-entry error: The truck had the correct 1-Bar MAP sensor for the application, but in the past someone had told the software the setup was using a 3-Bar MAP sensor, which is usually reserved for high-boost, forced-induction packages. Once the proper MAP sensor was correctly entered into the software, the readings normalized.

The problem was with the connector, not the IAT itself. Josh fixed the termination problem and the sensor started responding normally. Mike says, “I then went through all the other sensor data to make sure it correlated with the actual situation. It did, so we moved on.” With improper data input and sensor issues resolved, Mike can proceed to actually tuning the engine.

The problem was with the connector, not the IAT itself. Josh fixed the termination problem and the sensor started responding normally. Mike says, “I then went through all the other sensor data to make sure it correlated with the actual situation. It did, so we moved on.” With improper data input and sensor issues resolved, Mike can proceed to actually tuning the engine.

The Fix: IAT Connector

Making sure all the sensors are correctly working is yet another aspect of getting an EFI system working properly. Looking at the various data coming in during the initial tuning call, Mike noticed “the inlet air temperature [IAT] sensor was reading –30 degrees Fahrenheit—which was not correct, as Josh said it was about 70 degrees in his shop.” The problem was traced to bad wire termination at the IAT connector.

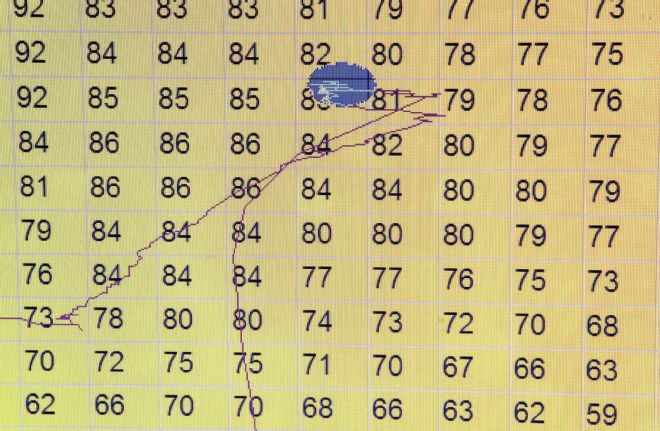

BigStuff3 uses engine volumetric efficiency (VE, entered in percent) for its fuel map. Engine dyno values are ideal, but Mike can get pretty close based on his vast real-world experience. “With an accurate VE curve, you can change everything else, and the system automatically recalibrates”—unlike some competitors that use actual pulse-width numbers that require manual recalculation every time a change is made.

BigStuff3 uses engine volumetric efficiency (VE, entered in percent) for its fuel map. Engine dyno values are ideal, but Mike can get pretty close based on his vast real-world experience. “With an accurate VE curve, you can change everything else, and the system automatically recalibrates”—unlike some competitors that use actual pulse-width numbers that require manual recalculation every time a change is made.

The other major screen is for constructing an Ignition curve. “I base the table off of experience,” Mike explains. “You want more timing at peak power, less at peak torque. You also need lots of timing down low.” Such a wave-like, high-low-high shaped timing curve isn’t possible with old-school mechanical-advance—but is a cinch with electronic engine management.

The other major screen is for constructing an Ignition curve. “I base the table off of experience,” Mike explains. “You want more timing at peak power, less at peak torque. You also need lots of timing down low.” Such a wave-like, high-low-high shaped timing curve isn’t possible with old-school mechanical-advance—but is a cinch with electronic engine management.

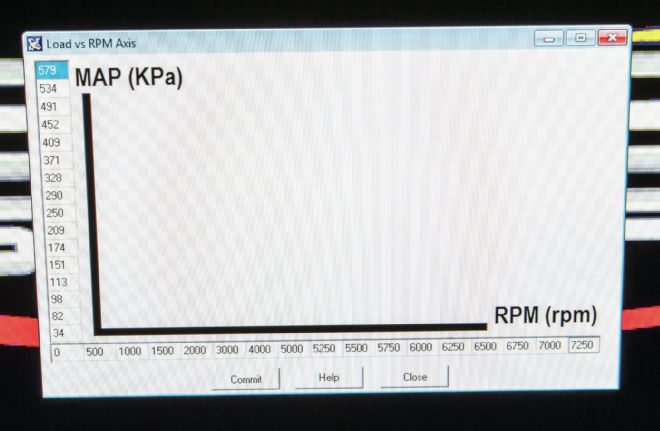

Lesser-known tuning screens provide the savvy tuner with loads of additional options. This is a load (vacuum) versus rpm chart. Once Mike determines how the engine will be used, he can make changes here that will alter the resolution of the fuel and spark map cells so the majority of their area is available for calibrating in the critical areas most needed by the motor.

Lesser-known tuning screens provide the savvy tuner with loads of additional options. This is a load (vacuum) versus rpm chart. Once Mike determines how the engine will be used, he can make changes here that will alter the resolution of the fuel and spark map cells so the majority of their area is available for calibrating in the critical areas most needed by the motor.

The Fix: Final Tune-Up

After resolving all physical issues, the engine could finally be started and properly calibrated. “Getting to this point where the engine is running and I am tuning the engine is always my goal,” Mike says. “But usually, the lead up to this point is where the customer can help themselves the most.”

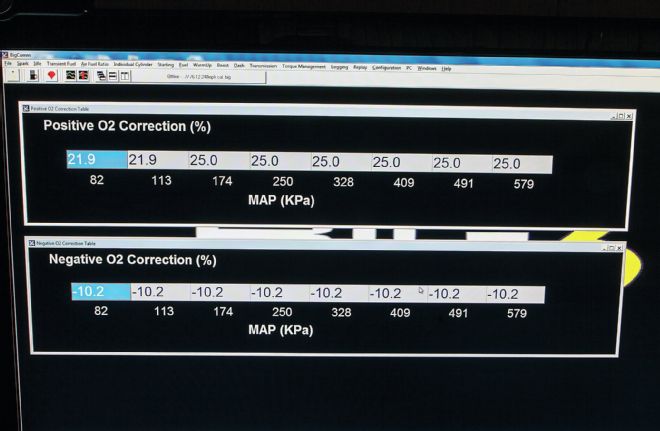

The O2 sensor correction page provides a fail-safe mode if the sensor starts to go bad or the fuel pump fails. A “positive” correction allows the ECU to add more fuel if a lean condition is sensed; “negative” subtracts fuel. “I allow up to 25 percent enrichment off of nominal, but just a 5 percent lean-out. It’s better to fail rich than lean so you won’t hurt the motor.”

The O2 sensor correction page provides a fail-safe mode if the sensor starts to go bad or the fuel pump fails. A “positive” correction allows the ECU to add more fuel if a lean condition is sensed; “negative” subtracts fuel. “I allow up to 25 percent enrichment off of nominal, but just a 5 percent lean-out. It’s better to fail rich than lean so you won’t hurt the motor.”

As seen from Josh’s perspective, “Mike installed a starter calibration. We attempted to start the vehicle, and Mike took a look at what is going on with the vehicle. He could see my screen and control my laptop computer remotely—very cool. During each session, he had me shut the engine off at various points so he could make changes to the [calibration].” After Mike finished, the fuel tables, spark curve, and cold-start characteristics were all specifically optimized for the Silverado.

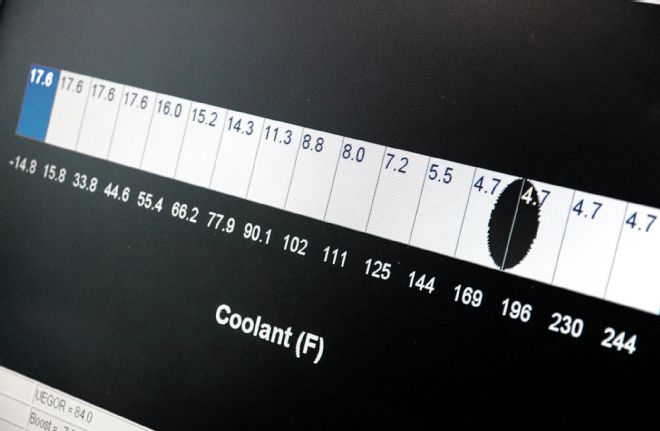

Properly configuring the various cold-start screens will get your EFI-equipped hot rod to start up as easily and quickly as a late-model stocker, even permitting use of a remote-start key fob. There are four key screens: cranking fuel enrichment percent over the base fuel map, decay rate (enrichment duration), after-start enrichment, and (shown) cold-enrichment amount based on coolant temperature.

Properly configuring the various cold-start screens will get your EFI-equipped hot rod to start up as easily and quickly as a late-model stocker, even permitting use of a remote-start key fob. There are four key screens: cranking fuel enrichment percent over the base fuel map, decay rate (enrichment duration), after-start enrichment, and (shown) cold-enrichment amount based on coolant temperature.

“The process usually takes 1 to 1.5 hours,” Mike says. “In this case, not counting playing phone tag, we had about 2 hours into the whole deal.” For this procedure, Mike charges $300 for the initial hookup and $150 per hour. He also offers a 10 percent military discount.

The Results

After all the tuning, the truck will do a burnout all the way through Third gear. “I was really impressed with the tuning capability,” Josh relates. “Before we got the system tuned, I wasn’t sold on it, but now I would build other vehicles with this package. It’s pretty expensive, but it seems worth it. I now want to learn more about how to do it. It definitely is a complex process, but it is something that is possible to understand.” Owner Greg chimes in that his truck now runs awesome. “I can’t keep my foot out of it,” he says. “It starts perfect and runs cool. My original plan was to use the truck to trailer my Nova race car to the dragstrip, but now I plan to run the Silverado there, too!”

Lessons Learned

There’s an old computer-geek saying: “Garbage in, garbage out.” In other words, if you have bad input, you can’t expect good output. As applied to automotive engine management, this means the sensors must be correct for the application and be operating properly, and the right information and initial setup values must be entered into the program. If these basic parameters aren’t set correctly, you’ll just spend time chasing your tail. It’s another case of “back to basics.”

Smartphone tuning has arrived—at least at the remote tuner end. “This is my Verizon hot spot that I use for an Internet connection to tune remotely while I am away from my office,” Mike says. “It works great while I’m driving down the road.”

Smartphone tuning has arrived—at least at the remote tuner end. “This is my Verizon hot spot that I use for an Internet connection to tune remotely while I am away from my office,” Mike says. “It works great while I’m driving down the road.”

However, if there are no sensor problems and the basic parameters are correctly entered on the initial setup screen, BigStuff3 can generate a decent baseline curve automatically. But if you want your ride to start and run just like a brand-new factory car under any and all conditions, as well as squeeze out maximum power and torque, an experienced tuner such as Mike who’s familiar with the system’s optional screens and subtleties comes highly recommended.

As for the remote tuning process itself, following directions is critical. Mike says, “One of the most difficult aspects of doing remote tuning is people not listening to what I am asking them to do or deciding what I asked them to do is not really needed. I tune every day and night of the week, so I have a pretty good idea of what is needed when I get into a situation. Josh is a smart guy. He listened intently to what I asked him to do and he got each request done quickly and correctly. Working with him was a pleasure, as he just knocked out whatever we needed in a quick and efficient manner.”

Top Four EFI Mistakes

Mike Moran continually sees these same mistakes. It’s imperative to get the following issues resolved before trying to dial-in an aftermarket EFI system.

1. Injector size not correctly entered on the BigStuff3 calibration screen: “Either the customer didn’t know the injector size at all, or they didn’t know how to convert the value from lb/hr to cc/min”: 1 lb/hr is about equal to 10.5 cc/min.

2. Wrong base timing: “This messes people up all the time. The initial ignition timing position is set so the computer can calculate the required timing, based on all the sensor inputs, and change it if needed. On a traditional racing distributor, the base timing needs to be 45 degrees BTDC, but on a conventional HEI distributor, it needs to be 6 degrees BTDC.”

3. Sensor not reading correctly: “Sensors are using voltage to ‘read’ whatever conditions they experience, so if the voltage is not being correctly reported, it is often the wiring that is the culprit. Sometimes the sensor has gone bad (especially O2 sensors), but the majority of the time, it is the wiring.”

4. Improper electrical grounds: “EFI systems don’t work properly if the grounds don’t go back to the battery’s Negative post.” Sensors operate under minute voltage variations, so any voltage fluctuations, resistance, or drop can introduce erroneous readings. Remember, the circuit’s ground-side is part of the total circuit length, and hence, contributes to resistance and voltage drop. A standard chassis-ground won’t cut it.

Now, Greg can’t keep his foot out of it. Originally intended as just a daily driver, he now plans to run it at the drags, too.

Now, Greg can’t keep his foot out of it. Originally intended as just a daily driver, he now plans to run it at the drags, too.