With most casting today, the process starts at the computer, where a part has been designed and needs to be developed for precision sand-casting. The part is broken down to determine how many molds and cores (the internal cavities of the part) will be needed, including vents for expansion, runners to help carry the molten aluminum, as well as formulas to determine material shrinkage.

Aluminum ingots of different grades are waiting on pallets to become everything from an elaborate air valve for trains to Hemi heads and Chevy small-blocks.

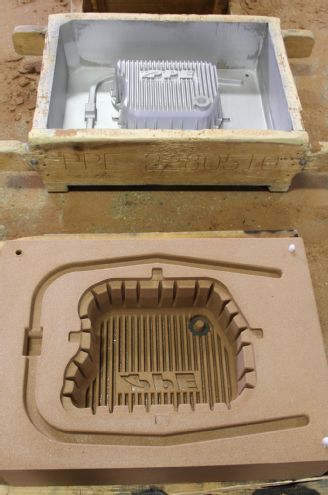

Patterns are created for each section of the mold. From these patterns the actual sand molds will be made, one mold per part. Within these patterns are the paths for metal flow called runners or sprues, vents for metal expansion as it cools, and supports for any cores needed to create cavities or passages in the finished part.

A mold box is made for the combined sections of the mold. Sand is poured into and compressed inside of the box creating the contained mold. The pattern and box are at the top, and the resulting compressed sand mold is at the bottom.

Molten aluminum is heated to the consistency of water so it can be poured without creating turbulence that might create trapped air pockets and result in porosity in the finished part. Temperatures also affect conditions where oxides form from saturated gases, how material leeches into the surface of the mold, and interference from areas solidifying at different times. Consistency of solidification is required.

The furnaces keep the aluminum molten as new ingots are introduced. The molds travel by conveyor into the furnace and then the metal is poured. The mold is then slid down a conveyor, while the next mold is inserted, and the process repeats.

Once out of the furnace, the mold is removed from the box and allowed to cool. Once cooled, all of the sand will be chipped away revealing the raw part.

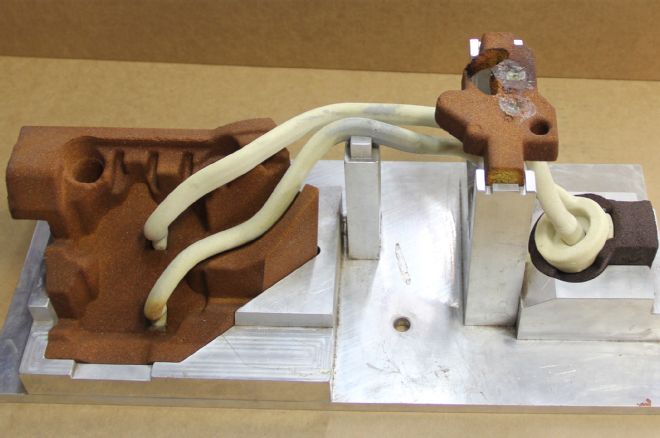

These are raw castings with sprues and runners attached after removal from the molding box but before any cleanup. You can see black sand from the mold clinging to the surface of the parts.

After the parts go through a rough cleaning, the sprues, vents, runners, and casting flash are cut, sanded, or filed off.

In the age of robots and automation, there is still a lot of handwork needed with the sand-cast method. Workers file and grind off flash and remnants of any vents or risers to end up with a finished casting that can be sent to a separate section of the Buddy Bar Casting facility for machining and drilling.

Inspection is the next step. These oil-filter relocators for 2015 Mustang right-hand-drive cars have been inspected and rejected for various flaws and will not be moving on to the machining and drilling process. They will be melted down and the aluminum reused.

Going back a couple of steps, this is the core setup for the Mustang filter relocators. Compare this to the previous image to get an idea of how the cavities inside of the part are configured.

Each cast part is fed into a five-axis mill, where it is secured before the computer program determines the drilling and machining necessary to complete the part. The automation allows for different steps to be performed at the same time. Once completed, the part is sent for final inspection, cleaning, and packaging.

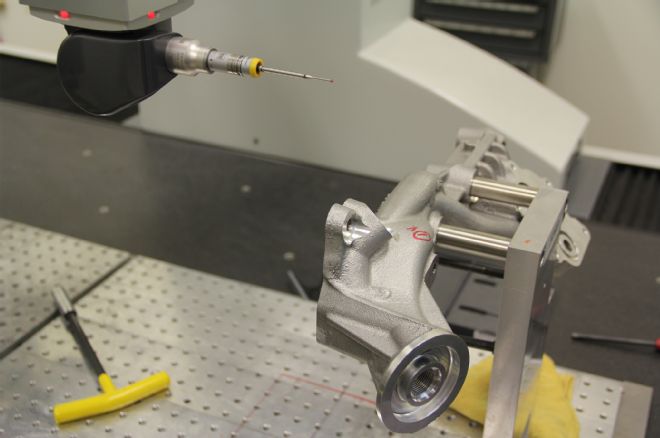

Parts are randomly selected during a run to be checked with a laser probe to determine any variances from tolerances set by the customer. This Mustang filter relocator has been secured into the machine and is in the process of being checked at hundreds of critical points inside and out.

A final inspection and clean-up before these Hot Heads Hemi (HotHemiHeads.com) heads are sent off for shipping.

The finished Mustang filter relocators ready for shipment to Ford. Buddy Bar has been doing aluminum casting for Ford since back in the 1960s when it did all of Ford’s Cobra and NASCAR racing components.