The fifth generation of the classic Chevy small-block V8 engine launched in GM’s 2014 fullsize trucks and SUVs and in the seventh-generation 2014 Corvette Stingray. Dubbed LT1 in the Corvette, it is the third small-block in history bestowed with the “LT1/LT-1” designation, and despite sharing a cam-in-block architecture and 4.400-inch bore centers, the latest version has about as much in common with the previous versions as Erica Enders-Stevens’ Pro Stock Camaro has in common with Grumpy Jenkins’ original Pro Stock Vega.

As it turns out, the new LT1 shares little more than an architectural lineage with the previous-generation LS engines, as well. For one thing, the heads are completely different—with the valves’ positions reversed—and designed to support direct-fuel injection (where the fuel injectors spray directly into the combustion chambers, instead of into the intake manifold as on an LS). The oiling system is different, too, and supports GM’s Active Fuel Management (cylinder deactivation) system. The new engine also incorporates continuous camshaft phasing (variable-valve timing), with a camshaft that features an additional lobe at the rear that drives a high-pressure fuel-injection pump mounted on the engine.

In short, almost nothing interchanges between the 1997–2013 LS engines and the new LT1, making “LT” performance a brave new world. It’s a challenging world, too, as the ultra-high-pressure direct-injection fuel system (operating at around 2,175 psi compared to the approximately 60 psi of a conventional port-injection system) and cam phasing mean traditional enhancements employed with LS engines either don’t work or require exponentially more investment to achieve comparable results.

At a glance, the 2014 Chevrolet Gen V LT1 block is clearly an evolution of the Gen III and Gen IV LS blocks. But there are architectural changes designed to accommodate an engine-mounted, high-pressure fuel pump for direct fuel injection, as well as different sensor locations, different engine-mounting provisions, and a number of other small changes. Like the LS3, it has 4.06-inch bores. The Katech stroker package hones them out to 4.07 inches.

At a glance, the 2014 Chevrolet Gen V LT1 block is clearly an evolution of the Gen III and Gen IV LS blocks. But there are architectural changes designed to accommodate an engine-mounted, high-pressure fuel pump for direct fuel injection, as well as different sensor locations, different engine-mounting provisions, and a number of other small changes. Like the LS3, it has 4.06-inch bores. The Katech stroker package hones them out to 4.07 inches.

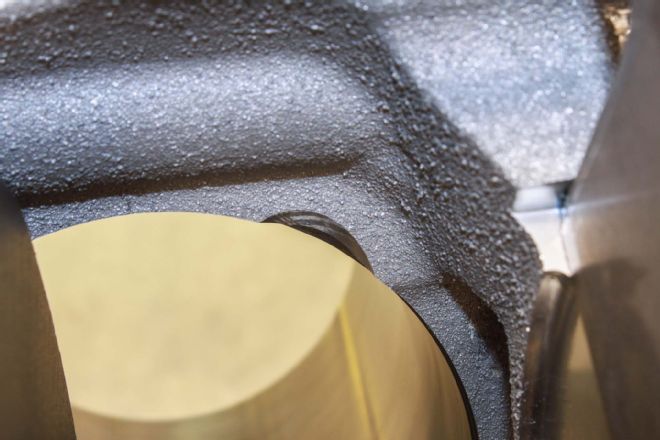

Katech’s preparation of the block for its 427ci stroker assembly requires minor notching of the aluminum block’s cylinder bottoms to provide adequate clearance for the longer throw of the connecting rods.

Katech’s preparation of the block for its 427ci stroker assembly requires minor notching of the aluminum block’s cylinder bottoms to provide adequate clearance for the longer throw of the connecting rods.

From the base 4.3L V6 truck engine to the LT1 in the Corvette Stingray, all Gen V–based engines feature oil-spray piston cooling that drenches the underside of the pistons and cylinder walls to maintain optimal piston temperatures and increase durability. Unfortunately, the stock oil-jet design (top) doesn’t mesh with Katech’s stroker package, so it developed custom jets based on a version from its high-performance LS7 engines.

From the base 4.3L V6 truck engine to the LT1 in the Corvette Stingray, all Gen V–based engines feature oil-spray piston cooling that drenches the underside of the pistons and cylinder walls to maintain optimal piston temperatures and increase durability. Unfortunately, the stock oil-jet design (top) doesn’t mesh with Katech’s stroker package, so it developed custom jets based on a version from its high-performance LS7 engines.

The LT1’s challenges haven’t stopped builders and tuners from jumping in to extract more from the latest small-block, but many have relied on the comparatively simple solution of bolting on a supercharger. It’s basically the big-hammer approach and is undeniably effective.

Detroit-area-based Katech, Inc. has taken a decidedly different tack, foregoing forced induction in the pursuit of naturally aspirated horsepower. It took more research and development than bolting on a blower, but the company’s long involvement in road racing was at the core of its methodology.

The LT1 comes with a steel crankshaft from the factory, so it’s almost a shame to toss it overboard, but achieving the significant 51ci increase in displacement requires the use of a new 4.100-inch-stroke crank. Katech uses a Callies 4340-forged piece.

The LT1 comes with a steel crankshaft from the factory, so it’s almost a shame to toss it overboard, but achieving the significant 51ci increase in displacement requires the use of a new 4.100-inch-stroke crank. Katech uses a Callies 4340-forged piece.

Thanks to the LT1’s variable-valve-timing system, achieving significant power gains in an LT1 engine is much tougher with a basic camshaft swap. Katech uses one based on its street/track LS7 K501 cam grind, but would rather keep mum on its specs. We can say, based on hearing the engine on the dyno, it delivers good idle characteristics without a lot of apparent overlap. The added displacement of the engine helped make the most of the cam’s capability.

Thanks to the LT1’s variable-valve-timing system, achieving significant power gains in an LT1 engine is much tougher with a basic camshaft swap. Katech uses one based on its street/track LS7 K501 cam grind, but would rather keep mum on its specs. We can say, based on hearing the engine on the dyno, it delivers good idle characteristics without a lot of apparent overlap. The added displacement of the engine helped make the most of the cam’s capability.

Forged Callies Compstar H-beam connecting rods provide greater strength than the original rods and feature the stock 6.125-inch length, giving the engine a rod/stroke ratio of 1.49. The pistons are an exclusive forged-aluminum design made for Katech by Mahle. The factory LT1 uses hypereutectic cast pistons.

Forged Callies Compstar H-beam connecting rods provide greater strength than the original rods and feature the stock 6.125-inch length, giving the engine a rod/stroke ratio of 1.49. The pistons are an exclusive forged-aluminum design made for Katech by Mahle. The factory LT1 uses hypereutectic cast pistons.

“Forced induction unquestionably gets the job done when it comes to adding horsepower to the LT1, but there are many people who prefer a naturally aspirated combination, especially on the track,” says Jason Harding, Katech’s director of aftermarket operations. “Supercharger heat soak, as well as coolant and oil temperatures, are real concerns during long tack sessions, and in that regard, a naturally aspirated engine offers greater consistency in power delivery—and it’s less likely to cause you to end a session early or back off due to excessive engine oil temps.”

There’s also a weight penalty with a blower, such as the one on the new Corvette Z06’s supercharged LT4 engine. An estimate of the integrated supercharger and intercooler assembly and related plumbing’s impact on the engine has to be around 50 pounds more than the negligible weight of the LT1’s plastic intake manifold. Those extra pounds are right over the front axle line, too, where they can affect balance and turn-in attributes.

The new pistons retain the unique piston-face topography of the originals—note the unique “scoop” in the center—because it’s essential for optimal combustion with the direct-injection fuel system. The compression ratio for the stroker 427, however, is raised from the stock 11.5:1 to 12.5:1.

The new pistons retain the unique piston-face topography of the originals—note the unique “scoop” in the center—because it’s essential for optimal combustion with the direct-injection fuel system. The compression ratio for the stroker 427, however, is raised from the stock 11.5:1 to 12.5:1.

Compared to previous LS engines, the LT1 has an all-new windage tray design with a new oil scraper designed to improve oil-flow control and bay-to-bay breathing. Like the cylinder block, it required a smidge of clearance to prevent interference with the connecting rods.

Compared to previous LS engines, the LT1 has an all-new windage tray design with a new oil scraper designed to improve oil-flow control and bay-to-bay breathing. Like the cylinder block, it required a smidge of clearance to prevent interference with the connecting rods.

Camshaft degreeing is important in an engine with variable-valve timing, and Katech uses this super-trick, electronically measured apparatus to do the job. Katech says it spent hours playing with the camshaft-phasing system to learn what the engine likes best.

Camshaft degreeing is important in an engine with variable-valve timing, and Katech uses this super-trick, electronically measured apparatus to do the job. Katech says it spent hours playing with the camshaft-phasing system to learn what the engine likes best.

[Editor’s note: Superchargers take engine power to spin—power that’s not going to the wheels. Superchargers also create heat as they make air pressure. That heat can be dissipated by intercoolers, but the intercoolers are typically not sized for lap-after-lap racing. High-power, naturally aspirated engines need lots of cooling too—as is evident by the supplemental oil cooling Chevy added to the 427ci Z/28.]

Katech was committed to naturally aspirated horsepower and achieved it by stroking the LT1 to 427 ci (7.0L)— a 13.5 percent increase over the stock 376 ci (6.2L). “We looked at the power level of the K501 camshaft in our [LS-based] Track Attack LS7 package, calculated the added power from compression, direct injection, and cam phasing in the LT1 and set an ambitious goal of 700 hp,” Harding says. “In fact, for anyone who wants the latest technology, it’s a combination that offers a tremendous performance range.”

Although cam phasing was retained on the 427ci stroker, the standard Active Fuel Management (cylinder deactivation) system was not. That required blocking off the oil feed provisions for the stock collapsible hydraulic lifters and replacing the lifters with conventional hydraulic versions.

Although cam phasing was retained on the 427ci stroker, the standard Active Fuel Management (cylinder deactivation) system was not. That required blocking off the oil feed provisions for the stock collapsible hydraulic lifters and replacing the lifters with conventional hydraulic versions.

Katech developed a lifter valley block-off plate to replace the stock one, which had provisions for Active Fuel Management. The new aluminum plate also serves as the mounting pad for the direct-injection system’s camshaft-driven, high-pressure fuel pump. It’s available separately for builders deactivating the cylinder-deactivating system on their own LT engines.

Katech developed a lifter valley block-off plate to replace the stock one, which had provisions for Active Fuel Management. The new aluminum plate also serves as the mounting pad for the direct-injection system’s camshaft-driven, high-pressure fuel pump. It’s available separately for builders deactivating the cylinder-deactivating system on their own LT engines.

The LT1 cylinder-head design represents another significant departure from the LS architecture. Katech says testing shows it generally flows better than an LS3 head, but not quite as well as an LS7 head. The rectangular intake ports are somewhat straighter than an LS3’s ports, with a slight twist to enhance mixture motion. Katech CNC-ports them in-house to enhance airflow for the greater needs of the larger-displacement 427.

The LT1 cylinder-head design represents another significant departure from the LS architecture. Katech says testing shows it generally flows better than an LS3 head, but not quite as well as an LS7 head. The rectangular intake ports are somewhat straighter than an LS3’s ports, with a slight twist to enhance mixture motion. Katech CNC-ports them in-house to enhance airflow for the greater needs of the larger-displacement 427.

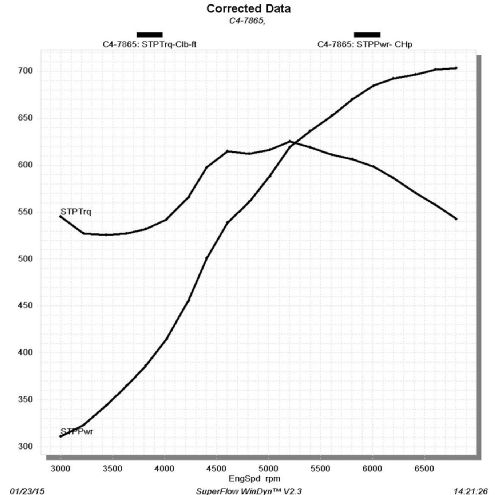

Katech’s engine made 703 hp at 6,800 rpm and 625 lb-ft of torque at 5,200 rpm, compared to Chevrolet’s supercharged LT4’s 650 hp. It’s also nearly 55 percent greater output than the LT1’s standard 455hp output. We should qualify the numbers here by pointing out Katech’s LT1 numbers were factored with STP correction math and Chevrolet’s official power numbers use a SAE correction factor to produce the output number. That means Katech’s numbers are higher than they would be with comparable SAE correction—perhaps around 4 percent.

Harding went on to say, “Displacement increase and head/cam change did give us similar improvements to LS engines; in fact, our LT1 head and cam package makes more power than a comparable LS3, but our lofty goal of 100 hp per liter in a driveable street package on pump gas left us with lots of disappointing moments on the dyno,” he says. “We pressed on testing more prototype parts and learning how the cam phaser likes to interact with them and eventually achieved our goal.”

Compared to the LS3 cylinder-head design, the LT1 head features a smaller 59.02cc combustion chamber designed to complement the volume of the piston’s dish—and, consequently, machining the chambers is not a good idea. Doing so jacks with the direct-injection system’s fine-tuned atomization, which could severely affect performance. The 2.13- and 1.59-inch valves are reversed from the positions of LS engines and are held at new 12.5 degrees intake and 12 degrees exhaust angles versus the LS3’s 15-degree angle. Additionally, the valves are splayed at 2.61 degrees intake and 2.38 degrees exhaust to reduce shrouding and enable greater airflow.

Compared to the LS3 cylinder-head design, the LT1 head features a smaller 59.02cc combustion chamber designed to complement the volume of the piston’s dish—and, consequently, machining the chambers is not a good idea. Doing so jacks with the direct-injection system’s fine-tuned atomization, which could severely affect performance. The 2.13- and 1.59-inch valves are reversed from the positions of LS engines and are held at new 12.5 degrees intake and 12 degrees exhaust angles versus the LS3’s 15-degree angle. Additionally, the valves are splayed at 2.61 degrees intake and 2.38 degrees exhaust to reduce shrouding and enable greater airflow.

Porting the LT1 head is a delicate operation, as these before and after images show. In fact, the bump in the port seen at the middle of the photo on the left, shouldn’t be touched at all, as these images illustrate. The hole created by its removal opens up the mounting hole for the rocker arm. Katech showed us its trial-and-error head to demonstrate the boundaries as LT1 performance continues to evolve.

Porting the LT1 head is a delicate operation, as these before and after images show. In fact, the bump in the port seen at the middle of the photo on the left, shouldn’t be touched at all, as these images illustrate. The hole created by its removal opens up the mounting hole for the rocker arm. Katech showed us its trial-and-error head to demonstrate the boundaries as LT1 performance continues to evolve.

Those comments echo what we’ve seen and heard from others in the industry, as promised head-and-cam packages and other modifications have been late to market. In some cases, the gains tuners have made haven’t met cost-to-benefit ratios that many customers will expect—particularly when compared to the large yet relatively inexpensive gains achieved with LS engines.

There are additional considerations, including higher-rate injectors for high-horsepower engines. With direct injection, they’re very specialized, Piezo-style injectors, sort of like what’s used in a diesel engine. And if you’ve ever tinkered with a common-rail 6.6L Duramax engine, you know their injectors can run from around $1,200 a set to more than $3,000. Injectors to fit the LT1 aren’t quite that expensive, but nonetheless a factor when a set of 80–lb-hr injectors for an LS3 engine can be had for less than $600.

On go the heads. Katech uses ARP head studs in place of the factory cylinder-head bolts. Note the raised position of the intake ports, compared to an LS head, and the holes below the lower-right corner of the ports. They aren’t mounting pads for the intake manifold, but the locations for fuel injectors, which protrude directly into the combustion chamber.

On go the heads. Katech uses ARP head studs in place of the factory cylinder-head bolts. Note the raised position of the intake ports, compared to an LS head, and the holes below the lower-right corner of the ports. They aren’t mounting pads for the intake manifold, but the locations for fuel injectors, which protrude directly into the combustion chamber.

The rocker arms should look familiar to anyone who has pulled the valve covers off an LS engine, but thanks to the reversed position of the valves, there are no longer offset intake-side rockers. Katech upgraded the beehive springs to lightweight PSI LS1511 384–lb-in springs to accommodate the new camshaft.

The rocker arms should look familiar to anyone who has pulled the valve covers off an LS engine, but thanks to the reversed position of the valves, there are no longer offset intake-side rockers. Katech upgraded the beehive springs to lightweight PSI LS1511 384–lb-in springs to accommodate the new camshaft.

Next, the stock fuel rails were installed and connected to the engine-driven, high-pressure fuel pump, which sends fuel to the injectors at around 2,175 psi. The fuel pressure for a conventional port-injected engine is around 60 psi and a carburetor is about 8 psi. The direct injection’s engine-mounted pump is fed by a traditional in-tank fuel pump.

Next, the stock fuel rails were installed and connected to the engine-driven, high-pressure fuel pump, which sends fuel to the injectors at around 2,175 psi. The fuel pressure for a conventional port-injected engine is around 60 psi and a carburetor is about 8 psi. The direct injection’s engine-mounted pump is fed by a traditional in-tank fuel pump.

That logically brings us to the tally for Katech’s stroker LT1. It was so new that it hadn’t been hit with the pricing gun yet, but Katech’s Street Attack LS7 lists for around $27,000 on the website. We’re guessing the LT1-based engine will be somewhere in that neighborhood. Whether it’s a little lower or a little higher, the bottom line is LT1 performance—in this period of its infancy—is as expensive as it is elusive.

Then again, a blower kit for an LT1 Stingray runs about $5,500 for a centrifugal kit to more than $8,000 for a roots-style blower. You can also count on another $3,000 or more for professional installation and tuning, so for those who prefer the pull of natural aspiration, Katech’s 427 engine is the best thing going.

The LT1 injectors are sort of like the Piezo-type injectors used in modern diesel engines for incredibly precise fuel control. They’re expensive compared to LS injectors and upgrade options are limited. Katech modified the stock LT1 injectors to deliver about 25 percent more flow to support the needs of the stroker 427, but now that the LT4 is available in the new Corvette Z06, those higher-rate injectors will likely make a more logical alternative.

The LT1 injectors are sort of like the Piezo-type injectors used in modern diesel engines for incredibly precise fuel control. They’re expensive compared to LS injectors and upgrade options are limited. Katech modified the stock LT1 injectors to deliver about 25 percent more flow to support the needs of the stroker 427, but now that the LT4 is available in the new Corvette Z06, those higher-rate injectors will likely make a more logical alternative.

Made of lightweight plastic, the LT1’s intake manifold is one of the reasons the naturally aspirated 427 combination will appeal to many enthusiasts. It doesn’t bring the weight penalty—and heat-soak issues—of a supercharger. Long passages inside the manifold are designed to generate big velocity at high rpm.

Made of lightweight plastic, the LT1’s intake manifold is one of the reasons the naturally aspirated 427 combination will appeal to many enthusiasts. It doesn’t bring the weight penalty—and heat-soak issues—of a supercharger. Long passages inside the manifold are designed to generate big velocity at high rpm.

Katech experimented with the stock electronically controlled throttle-body, a ported version, and a larger-diameter aftermarket version. The ported and larger-diameter versions delivered significant gains over the stock 87mm version.

Katech experimented with the stock electronically controlled throttle-body, a ported version, and a larger-diameter aftermarket version. The ported and larger-diameter versions delivered significant gains over the stock 87mm version.

The completed engine was tuned with the new Bosch E92 controller for a Corvette Stingray. It has provided another learning curve over previous LS engine performance, because it represents an all-new Bosch platform and more engine systems (such as oiling) are directed by it. Katech was tinkering with the system for about a year before tuning the 427.

The completed engine was tuned with the new Bosch E92 controller for a Corvette Stingray. It has provided another learning curve over previous LS engine performance, because it represents an all-new Bosch platform and more engine systems (such as oiling) are directed by it. Katech was tinkering with the system for about a year before tuning the 427.

On the dyno, the Katech 427 LT1 delivered 703 hp at 6,800 rpm and 625 lb-ft of torque at 5,200 rpm. The high-rpm capability is astounding, but just as important is torque production. From 3,000 rpm until the tachometer needle breaks off, the engine produces no less than 520 lb-ft—grunt that will quickly erase any second thoughts about not selecting a supercharger.

On the dyno, the Katech 427 LT1 delivered 703 hp at 6,800 rpm and 625 lb-ft of torque at 5,200 rpm. The high-rpm capability is astounding, but just as important is torque production. From 3,000 rpm until the tachometer needle breaks off, the engine produces no less than 520 lb-ft—grunt that will quickly erase any second thoughts about not selecting a supercharger.