One of the signature design features of traditional small- and big-block Mopar engines was the simple and effective shaft rocker arrangement. With few exceptions, these were minimalistic setups, featuring stamped-steel non-adjustable rocker arms and solid steel pushrods lined up on a large diameter (7/8-inch) shaft. Lubrication is handily provided by an oil passage coming up from the block, feeding the valvetrain through the hollow rocker shafts. With a hydraulic cam the factory rockers are actually quite effective, owing largely to the light weight and low inertia of the rocker design, plus the inherent stability of the large slabbed bearing area where the bottom of the rocker met the shaft. All is happy in Moparland until spring loads, high lift, or solid lifters enter the equation.

With high lift and spring loads, the rockers' strength becomes an issue, most apparently at the pushrod socket. Here is the most common failure point of the system, with the pushrod punching through the socket, skewering the rocker. The factory addressed this in later applications, offering heavier-duty rockers with more meat in this area, and even cataloged the heavy-duty stamped rockers through their performance parts program. While this was a step in the right direction, when stepping up to race-level spring loads, or when requiring adjustability or higher ratios, aftermarket rockers and valvetrains are the requirement.

Since the Mopar shaft system has a fixed fulcrum point, the rocker geometry is fixed by design of the rocker. Unlike the Chevy stud-mounted rockers, pushrod length has zero effect on the rocker-to-valve geometry or the sweep of the rocker at the valve. Think about it, you can bolt the shaft system to a head on the bench and work it with a crowbar (don't do this), and the way the rocker moves at the valve is exactly as it would be in the running engine. The only real consideration related to pushrod length with a stock-style shaft system is getting the valve lash adjuster in the correct range. In the old days when engine variations were far fewer, there were shelf pushrods for hydraulics with adjustable rockers, for solids, and of course for the stock valvetrain. With wide variations in cylinder heads and rocker designs these days, getting the right pushrod length requires measurement.

The Right Length

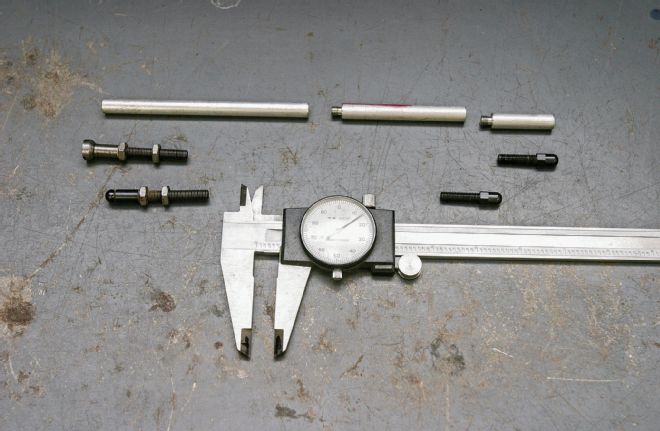

Mocking up and determining pushrod length is a fairly basic process. In your toolbox you will need an adjustable checking pushrod with the required ends. These tools are readily available from cam suppliers as well as specialty engine tool companies like Powerhouse. You will also need a way to measure the checking pushrod's length—a 12-inch caliper does the job here.

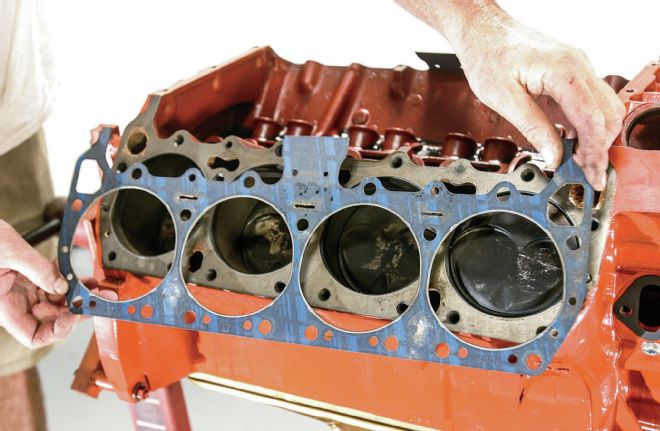

The engine needs to be mocked up as it will run, including the head gasket, as this affects the height of the head. An old compressed head gasket of the same type is best, though you can break out the new one and snug the head down to just seated with a couple of fasteners. Alternatively, if you'd rather not break out the new gasket, the compressed thickness can be added to the determined pushrod length. Park the cam so that the lifter you are measuring from is at the base circle, and then insert the checking pushrod and bolt on the rockers. Park the lash adjuster in the position it needs to run. Generally, with standard ball-type adjusters on the rocker side, the adjustment here should be with about 1.5 threads showing through the bottom of the rocker body.

An adjuster that hangs well below the rocker body will cost lift because of the increased angle, and will add stress to the adjuster. A pushrod that is too long will run the adjuster too high in the rocker body, and may result in shrouding the cup, foiling lubrication, and leading to smoked pushrods. With socket-style rocker adjusters such as the COMP Pro Magnum, the pushrod oiling is accommodated by an oil band in the adjuster. These should be set so that the oil passage is in mid-position.

With everything mocked up, all that is left is to wind out the adjustable pushrod to find the length. With a solid cam, insert a feeler gauge at the lash specification at the valve tip to simulate the required lash. With a hydraulic, the desired lifter preload can be added to the pushrod length once it is determined. Unbolt the rocker and measure the checking pushrod length with the calipers. Since most adjustable rockers for Mopar shaft systems use cup end pushrods at the rocker side, the depth of the cup must be subtracted from the overall length measured to get the effective length of the pushrod. This is how pushrod length is cataloged for cup-style pushrods, and when ordering custom pushrods be sure to mention to the manufacturer that the length ordered is measured from the ball end to the bottom of the cup end. Repeat and measure the exhaust side separately, since often variation in valve tip height can cause variations between the intake and exhaust.

Pushrod Material & Configuration

When shopping pushrods you'll find a variety of available materials and sizes. Factory pushrods were 5/16-inch solid steel while aftermarket units are universally tubular. The solid design was not really stronger, just cheaper to manufacture, and it is obviously heavier. When selecting pushrods for a performance application, the most important aspect is stiffness. The tall decks of Mopar engines result in long pushrods, and long pushrods are more prone to flex than shorter ones. Pushrod flex leads to valvetrain instability, and this can seriously curb high-rpm power.

Racing has proven that stiffness is more critical than weight at the pushrod side of the valvetrain, so it pays to not compromise here. The best way to gain rigidity in a pushrod is by increasing the diameter, however wedge Mopars are typically limited in pushrod clearance. If practical, 3/8-inch pushrods are a better choice than the factory 5/16, but this change will require clearance work in many applications. When clearance is limited and rpm and valvespring loads are moderate, the 5/16 inch pushrod diameter will get the job done. High-strength material, heat treating, and heavier wall thickness can up the practical limits when retaining 5/16-inch pushrods. A specialist manufacturer can provide information on the appropriate pushrod material for a given application, taking into consideration the cam specifications, spring loads, and rpm requirements. It pays to take advantage of the expertise of specialists in the field.

Custom pushrods are certainly not required in every application. You will find cataloged pushrods in a variety of configurations that might be right for your application. In ball-end pushrods the field is fairly well covered, with catalog 'rods of various grades typically listed in 0.050-inch increments. Ball/cup pushrod selection is more limited as cataloged units, but often suitable pieces are listed, stocked, and ready to ship. Keep in mind that pushrod length generally isn't an item that needs to be exact to the thousandth of an inch. Take the measurement and check the catalogs and often you will find something that will work.

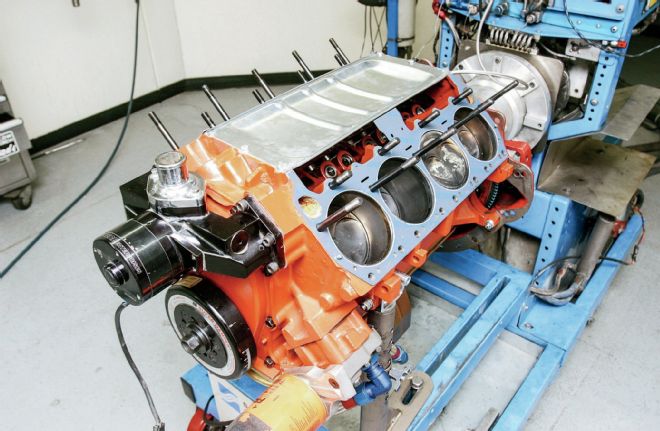

The pushrods required for the job depend on many factors including the block deck, cam and lifter type, and the top end and valvetrain parts. When we swapped this 383 to a set of Indy heads, a new set of pushrods were required.

The way to determine the required pushrod length is to have all the hard parts in hand and measure it directly. Items like the head gasket, which alter the height of the heads, need to be taken into account. We mocked ours up with a used gasket of the same type we will be running in the assembled engine.

Cylinder heads can create a major variation in the required pushrods. These Indy heads are much taller and use much longer valves than production units, so stock application pushrods are not even close.

The type of lifter and cam plays a role here, since the seat height in the lifter varies with the lifter design. These COMP solid lifters have a much deeper seat than a standard hydraulic. Also, the cam base circle diameter figures into the working height of the valvetrain. Rotate the crank to put the lifter being used at the cam's base circle.

To take a direct measurement of the required pushrod length, a checking pushrod kit is used, as well as a large caliper to take the measurement. The checking pushrods are available with interchangeable tips to match your pushrod configuration, and segmented bodies to allow a wide range of check lengths.

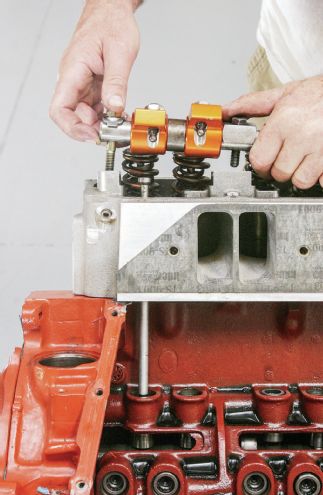

The valvetrain is mock assembled with the rocker adjuster put into the desired setting and checking pushrod in place. Different rocker bodies can have different pick-up points at the pushrod side, varying the required pushrods; here our rockers are Harland Sharp 1.6:1-ratio units. Typically, a ball adjuster is set with about a thread and a half showing below the rocker body.

With a solid-lifter cam, a feeler gauge takes up the space of the lash to compensate and the checking pushrod is adjusted to remove all slack from the system. With a hydraulic, you can simply measure at the zero lash position and then add the desired lifter preload to the pushrod length.

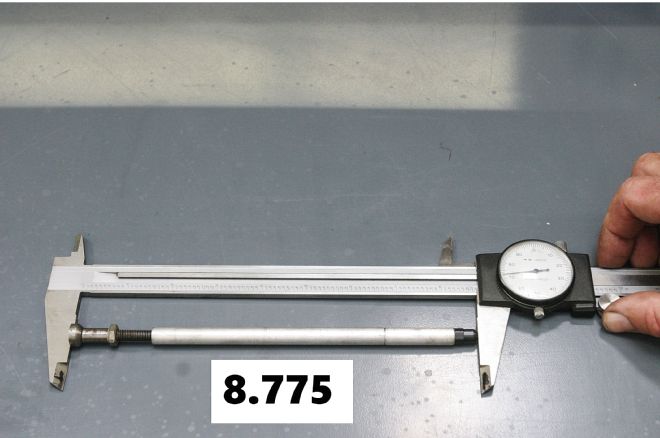

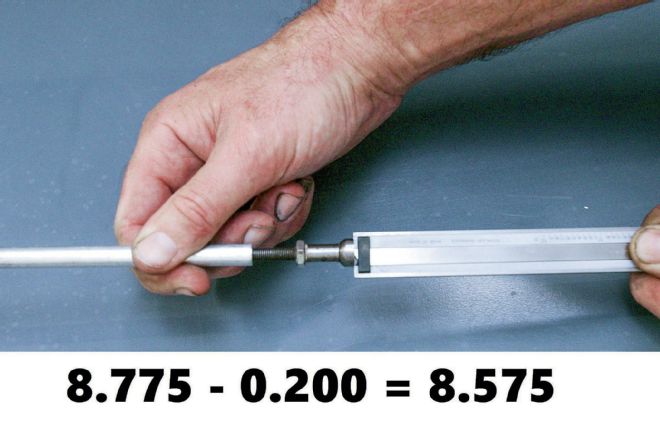

Remove the checking pushrod and take a measurement of the overall length using the calipers. Be sure the pushrod is square in the jaws for accuracy. In this case, the pushrod measures 8.775 inches.

The depth of the pushrod cup should be measured and subtracted to get the working length of the pushrod. Add in length to compensate for lifter preload with a hydraulic, or a head gasket if it was omitted from the mock up. Here we arrived at a final length of 8.575 inches after subtracting .200 from the initial 8.775 length.

Since there is often variation between the intake and exhaust side, it pays to go back and repeat the process for the exhaust valves. Ours checked in pretty much identical to the intake side.