Chrysler's big-block wedge has always been a staple of Mopar street performance for good reason. As the engine with the biggest factory displacement, the cubes are already there for ample power production, and the rugged bottom end components endowed by the factory are built to go the distance. Sure, we would all like a monster stroker engine combo filled with a catalog of aftermarket parts, but a sweet street cruiser with plenty of punch is as simple as building on what the factory delivered. For the budget-minded Mopar fan, the 440 offers an abundance of cheap power with a few basic upgrades to step up the areas where the factory 440 is a little short.

The Good, the Bad, And The Ugly

Looking at the plus side, as mentioned, the 440 has the size, and most also have a factory forged crankshaft good for a reliable 6,500-plus rpm. Even the cast crank found in post '74 440s has proven brawny enough to handle revs in the 6,000-rpm range. That's good enough for us. Next, we have the connecting rods. As with the crank, a simple recon, inspection, and a set of bolts will yield a set of rods capable of reliable service to the same 6,000-rpm range as the aforementioned crankshafts. Although the most powerful factory stock 440 engines produced a rated 390 gross horsepower, the OEM blocks can take power in the 600hp range, and survive practically indefinitely at the 500-550hp level. Mopar built quite a bit of strength into the bottom end of these engines.

All factory 440s came with cast-aluminum pistons, and although the OEM units were surprisingly capable, the compression ratio requires consideration. Even the early high-performance 440 Magnum engines, rated at 10:1 compression, actually fell short of that specification. Later 440s suffered a significant drop in the compression height of the pistons, resulting in abysmally low compression ratios. Fortunately, these days affordable high-compression forged pistons are readily available from a number of manufacturers.

Up top, some of the factory combo's shortcomings start to become apparent. Although the valvetrain offers excellent geometry and is quite capable, the cylinder heads it was bolted to were marginal for an engine of the 440's displacement. Even the best of the standard big-block heads really delivered small-block–sized airflow. While extensive porting of the factory iron can remedy this situation, the economics involved dictate that a replacement set of cylinder heads is the most practical upgrade. The upshot here is that a cylinder head swap to aftermarket aluminum heads will support a higher compression ratio, improving detonation tolerance by virtue of the material's better thermal characteristics and the elimination of the outdated open-chamber design of the factory iron.

As with the cylinder heads, the induction system is a prime area for an effective upgrade. Unless we are dealing with a factory Six Pack setup, the 440 was saddled with a marginal iron two-plane manifold. Chrysler consistently used the same manifold across the board, so even if you have a factory high-performance Magnum engine as a starting point, the intake manifold is the exact same part fitted to a New Yorker or Imperial. In contrast, the Magnum 440 did receive a larger version of the Carter AVS carburetor, which is a fairly capable piece in a milder performance application. Nevertheless, tuning parts for these carbs have never been very readily available, and the airflow becomes a limiting factor when the combination is substantially stepped up.

Finally, we have the camshaft. With even the 440 Magnum cam's specifications of 208/221 duration at .050, .450/.458-inch lift, and a very wide 115-degree lobe separation, 440 cams were very conservative grinds. With today's camshaft technology offering much more aggressive rates of acceleration and velocity, there is plenty of room for improvement here, even when sticking to a hydraulic flat tappet. Large power gains are possible here without going wild and seriously compromising street driveability and vacuum. A modern aftermarket hydraulic flat-tappet cam is a very cost-effective upgrade, and the additional lift potential will work to perfectly complement the improved high-lift flow of a set of aftermarket cylinder heads for improved output.

As the engine with the biggest factory displacement, the cubes are already there for ample power production…

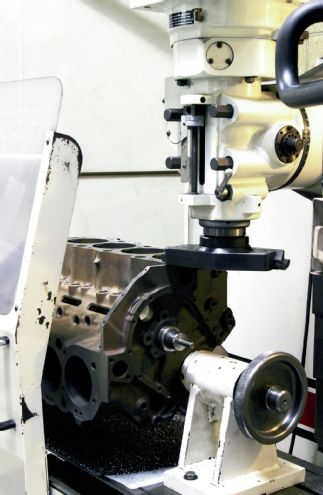

Costs can be kept down by keeping machining to a minimum. Our block received a cleaning, inspection, and then the only machining operations involved was having the block bored .030-inch and square-decked to zero piston deck height.

The factory-forged steel crankshaft is very durable, especially if it has led a soft life loafing along in a large C-Body. We ground the crank .010-under and installed it with Clevite bearings using Milodon studs.

Probe offers flat-top forged pistons that are a very good value and very durable in a street/strip application such as this. The flat-top pistons will deliver just under 10.5:1 compression with our combo.

Factory big-block rods are strong forgings and reliable in milder performance applications up to 6,500 rpm. The heavy-duty Six Pack rod (left) features a heavier beam than the standard rod, however, most failures are at the fasteners. We had our standard rods resized and fitted with ARP bolts.

Upgrade Where It Counts

In spelling out the 440's strengths and weaknesses, we basically laid out our entire build plan. The cost effectiveness comes from modifying the areas where the factory combination falls short, while retaining the components that will serve well in a basic street performance combination. Our build starts with a factory '70 440 as a core. This was not a muscle car engine originally, but just a standard 440 out of a C-Body. While the "HP" stamping on the engine's data pad may be a point of pride to some, the standard 440 used most of the same hard parts as the high-performance version. The blocks, cranks, and rods in most engines were the same across the board. Exceptions here that matter include the heavier-duty wide beam "Six Pack" rods used in '70-and-later 440 Magnum engines, and the factory windage tray and large capacity oil pan exclusive to the performance engines. The other items where there was a difference in specification involve parts that are going to be replaced in the course of a normal rebuild, such as the pistons, timing set, cam, and valvesprings.

Boiled down, our 440 received the basic machining operations, including cleaning and inspection, a .030-inch overbore and hone, and a decking to a zero piston deck height. The only real upgrade to the bottom end was substituting a set of forged Probe flat-top pistons for the cast stockers, and fitting the factory connecting rods with a set of ARP bolts. Our rods are the standard "LY" rods rather than the beefier Six Pack units, but the standard rod was well proven as up to the task in pre-'70 high-performance engines, and are favored by many Mopar engine builders for their lighter weight and factory internal balance. The OEM steel crank was cleaned up with a .010-inch regrind on the rods and mains, and installed with a set of standard MAHLE Clevite bearings. We used a set of Milodon studs to improve the clamping with the factory main caps, a simple and cost-effective upgrade. Speed-Pro file-fit Plasma Moly rings seal the pistons to the bores. Although there are cheaper rings, the wear resistance and durability of the moly rings make them well worth the added cost.

Up top, the airflow improvement came with simply opening the box on a set of Edelbrock Performer RPM heads. The heads certainly stepped up the flow, with a rated peak intake flow of 292 cfm, in contrast to the low 200-cfm range for a set of stock castings. Besides eliminating the cost and time involved in rebuilding the factory heads, the Edelbrocks come equipped with a fresh set of high-performance springs with all new hardware, and larger-than-stock valves. A further upshot is that these heads can handle considerably more valve lift without retainer-to-guide clearance issues, and come equipped with positive-style valve stem seals for improved oil control.

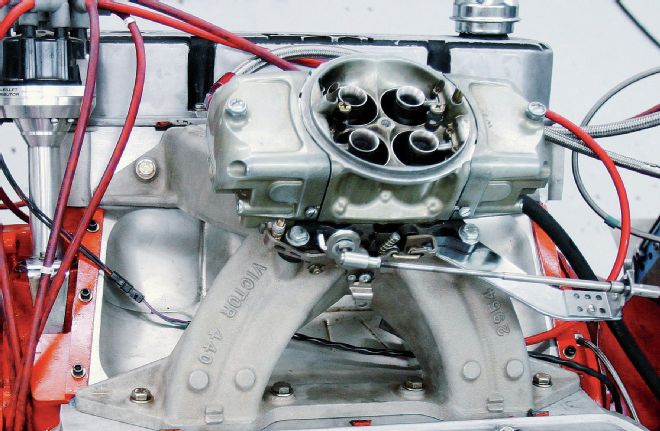

We also went with Edelbrock components for the intake, opting for the tall single-plane Victor manifold. While a Performer RPM two-plane manifold is generally a better choice for a street cruiser, our 440 was going to be more of a street brawler, destined for a Plymouth Duster with deep gears and a stall speed approaching 4,000 rpm. Here, the torque advantage of the RPM would be mostly lost, while the top end advantage of the single-plane will be welcome. To top the intake, we again went large, going with a 975-cfm Race Demon RS carb. Like the intake manifold, the carb favors top end power in keeping with the intended application.

Up top, the airflow improvement came with simply opening the box on a set of Edelbrock Performer RPM heads.

With the intention of retaining the factory valvetrain, a hydraulic flat-tappet cam was the only possible choice. COMP's XE285HL is a Mopar-specific grind with a very fast profile.

The factory Mopar valvetrain is a shaft-mounted non-adjustable stamped-steel arrangement. Although it seems inadequate, the rockers are very light and have good high rpm capabilities.

A set of Edelbrock RPM cylinder heads is a major upgrade in airflow, and come complete, ready to bolt on. The many advantages of these new heads make it a practical upgrade compared to factory iron.

With top end power in mind, we went with Edelbrock's single-plane Victor intake manifold. The long-runner Victor offers good lower-end torque for a single-plane, but a two-plane Performer RPM would be the best choice in a milder street application.

Our 440 was topped with a 975 Race Demon carb, again emphasizing top-end performance. The big Demon featured annular boosters to help response in the lower rev range.

The final item on the hit list was the camshaft. Here you want to use a cam that takes advantage of the more radical profile possible with the Mopar engine's large .904-inch diameter lifters. COMP offers a line of high performance cams ground to Mopar specifications, and you might notice the lift for any given duration number is higher than their standard cam offerings. This is because the maximum velocity of a flat-tappet cam is limited by the tappet diameter. With the large factory lifter, cam designers can take advantage of the more aggressive cam profiles possible with Mopar-specific cams. Our stick is a COMP Xtreme Energy High Lift hydraulic flat tappet, with specifications of 295/297 degrees gross duration, 241/247 degrees duration at .050-inch lift, and .545/.545-inch lift. Admittedly, this is a big cam, which will definitely make its presence known with that boulevard lope that echoes horsepower. COMP also offers Mopar-specific hydraulic flat-tappet cams with more conservative specification that would be more appropriate for more street-orientated builds.

Finally, we had the valvetrain to contemplate. We had a set of factory stamped-steel rockers from our core engine in very good condition, and a hydraulic flat-tappet cam stabbed in the engine. While a solid cam would force an upgrade to a set of adjustable rockers to replace the non-adjustable stockers, the hydraulic can work with the factory rockers. Though the OEM rockers are anything but attractive or high tech, they are extremely light and surprisingly durable. We were just at the edge as far as the valve lift at which we would consider the stockers, but many years of dyno testing big-block Mopars show that they are effective and rpm exceptionally well. We just cleaned them up and bolted them on.

On The Dyno

Our 440 was essentially a mild rebuild with selected upgrades of the heads, cam, compression, and induction. By keeping what we could of the factory components our cash outlay was very modest for a performance-minded build. To quantify just what such an engine is capable of we trucked the fresh bullet to Westech Performance Group for a ride on their SuperFlow 902 engine dyno. Packed along with the engine were a set of Hooker Competition Series 1 7/8-inch headers and an MSD distributor. We would also be using the MSD ignition box and coil that is part of the dyno facility to generate the spark. Up front, we had a stock iron water pump housing and a beltdriven stock replacement water pump. As a nod to vintage style, we bolted on a set of our favorite old Mickey Thompson valve covers and were ready to run.

Our goal was power cresting the 500hp mark, a level that is more than enough to move our lightweight Duster in a hurry. Upon firing the engine for adjustment and break-in, the generous camshaft specifications made themselves known with a definite idle lope and just under 8 inches of vacuum. With the total ignition timing set to a conservative 36 degrees, we went into the power pulls, and found the combination easily pulled past our 500hp target, with a peak of 537 hp coming in at 5,700-5,800 rpm. That is substantial power at an rpm range that the engine can survive at for a very long time. Looking at the torque, the numbers were also impressive, especially considering the substantial cam timing and the large single-plane intake manifold. At the lowest recorded rpm point the engine was well over 500 lb-ft, reading 527 lb-ft at just 3,600 rpm. That is sure to be a powerful hit with a loose drag-style torque converter. At peak, we had 538 lb-ft, spanning from 4,400 to 4,600 rpm, showing a relatively flat torque curve through most of the powerband. Power numbers like these from such an unassuming combination proves what Mopar enthusiasts have known for years: For power on a real-world budget the Chrysler 440 delivers the goods!

On The Dyno

440 Chrysler Big-Block

RPM: TQ: HP: 3,600 527 361 3,700 525 370 3,800 526 381 3,900 528 392 4,000 533 406 4,100 534 416 4,200 535 428 4,300 537 440 4,400 538 451 4,500 538 461 4,600 538 471 4,700 535 479 4,800 532 486 4,900 530 494 5,000 527 501 5,100 524 509 5,200 521 516 5,300 518 523 5,400 513 527 5,500 508 532 5,600 502 535 5,700 495 537 5,800 487 537 5,900 477 535 6,000 467 533

Power numbers like these from such an unassuming combination just goes to prove what Mopar enthusiasts have known for years...

On the dyno, our 440 responded with power that you would not expect from such a simple build. Horsepower peaked at 537 at 5,700-5,800 rpm, while plenty of torque was on hand, recording 538 lb-ft from 4,400 to 4,600 rpm.