"For Sale: used small-block Chevrolet engine—$200." We've all been there: staring at a crusty small- or big-block and wondering if that lump is any good. You can just chance it, or you can spend a little time checking before you buy. While most of this should be standard operating procedure, it's amazing the number of buyers who don't bother to do their research first. Obviously, the best test is to hear the engine run, but often, this isn't possible. However, there are still plenty of other clues to indicate an engine's condition; you must go armed with a few tools, in addition to the cash.

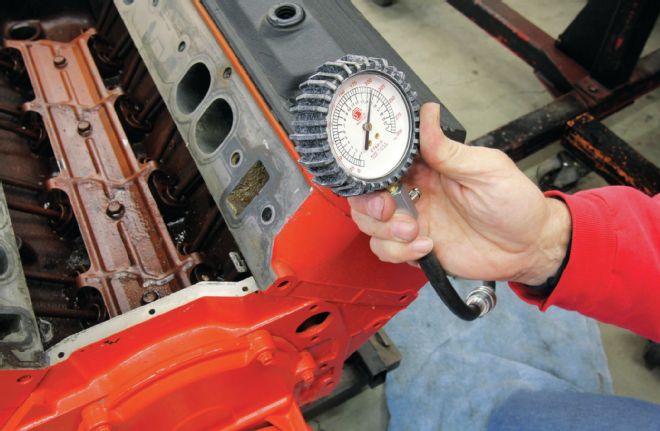

We tested three different engines: a small-block Chevy that looked pretty rough, a big-block Chevy that had been given a "Krylon rebuild" with Chevy orange, and a high-mileage 4.8L LS engine. All three turned out to be in decent shape. Our 4.8L LS engine produced a shocking 195–200 psi of cranking pressure and varied less than 8 percent among all cylinders. We attribute this to better engine-block metallurgy and a combination of very efficient fuel atomization and good lubricants that kept the rings fully sealed. Armed with a compression tester and a battery to crank the engine over, we'll show you the three different engines we investigated. While a higher-cranking compression number is good, you're really looking for consistency among all the cylinders. The accepted variance is usually 20 percent. So if we have an engine that cranks between 140 and 160 psi for all cylinders, only a 14 percent variation, that is acceptable. We have a few other tricks to offer along the way, so let's take a look.

Our first victim was listed as a 350 with a mild cam. According to Mark Allen's "Chevy Small-Block Suffix Codes" book, this CKD code is a 1972 through 1974 L48 or LM1 350 rated at between 160 and 200 hp. The engine had an iron intake and Quadrajet carburetor consistent with the book. We didn't try, but this engine could have easily been configured to run with just fuel and 12v to the distributor.

We yanked the dipstick and pulled the valve covers; everything looked decent with no sludge buildup. We also removed all the spark plugs. It appears the carburetor was jetted too rich, but there did not appear to be any oiling control problems and no massive carbon buildup on the plugs.

We were lucky that the engine still had a starter motor and battery cables. We volunteered the Optima battery out of our pickup, hooked the cables to the starter, and used a remote switch to spin the starter motor. We also had to block off the oil-pressure fitting on the back of the engine, or it would have pumped oil all over the engine.

We included the cranking pressures in the chart at the bottom right of the page. All eight cylinders were well within 20 percent of each other, so this appears to be a decent engine. Our pal Norm Brandes from Westech Automotive in Wisconsin told us to watch the pressure gauge carefully and note the pressure from the first time the piston creates pressure. The higher the first pressure reading is on the gauge, the better the ring seal.

Our second participant was this 1999 L-29 454 Gen VI big-block. Rated at 290 hp, it came with a hydraulic roller cam and no mechanical fuel pump boss. We assumed the cranking compression would be a little higher since it didn't have an intake manifold or carburetor. We used the portable battery box we built in the Mar. 2014 issue to supply cranking power.

At first, we thought we had a dead motor, as No. 1 only created 20 psi. But after squirting a little oil in the cylinder and spinning the engine for a few seconds, the pressure came up. As you can see by the chart (bottom right), this engine has great cylinder pressure. The engine was destined for a 1970 El Camino, so the oil pan needed to be changed. The engine turned out to run just great.

There are a ton of inexpensive compression testers on the market. Ours is a Matco but you can buy a budget tester from Summit Racing for as little as $20.97 (PN 900009).

We also looked at a used small-block Chevy short-block. This one obviously had been burning oil based on the amount of carbon on the pistons. If the rings are bad, the outside perimeter of the piston will often be clean where oil has washed away the carbon. This engine might have been suffering from bad valve guides, which could mean the rings and pistons are in decent shape. We also checked the deck height—just because we could. It was 0.018 inch.

We checked the bore with our dial caliper and discovered this is a 4.00-inch (standard bore) 350. The block stamp indicated a 160hp 1975 truck motor.

L-29 454ci big-block Chevy Test

Driver Side Passenger Side 1 – 200 psi 2 – 210 psi 3 – 205 psi 4 – 220 psi 5 – 180 psi 6 – 175 psi 7 – 190 psi 8 – 205 psi

LM1 350 ci small-block Chevy Test

Driver Side Passenger Side 1 – 140 psi 2 – 140 psi 3 – 140 psi 4 – 160 psi 5 – 165 psi 6 – 145 psi 7 – 140 psi 8 – 145 psi