It may not look like a big change, but the geometry of Comp Cams’ new conical valvespring stands to make it a real game changer when it comes to making horsepower in racing engines.

It may not look like a big change, but the geometry of Comp Cams’ new conical valvespring stands to make it a real game changer when it comes to making horsepower in racing engines.

These days circle track racing engines are so finely tuned—and so constrained by the rules—that any gains in power made are almost always incremental. For example, we know of one engine builder who actually spent time, and some serious coin, researching new materials for rear main seals that would create less drag from the seal’s contact with the crankshaft. The engine builder wins races pretty regularly, so we’re not saying he was wasting his time or money, but it does give you a good idea just how desperate engine builders are to continue raising the horsepower bar.

So any time you are able to make a significant gain, it definitely catches our attention here at Circle Track. And Comp Cams’ new conical valvesprings are a concept that definitely has the potential to help engine builders make significant gains in race engine performance from Street Stocks all the way up to the big guys that race on Sundays and hog all the glory.

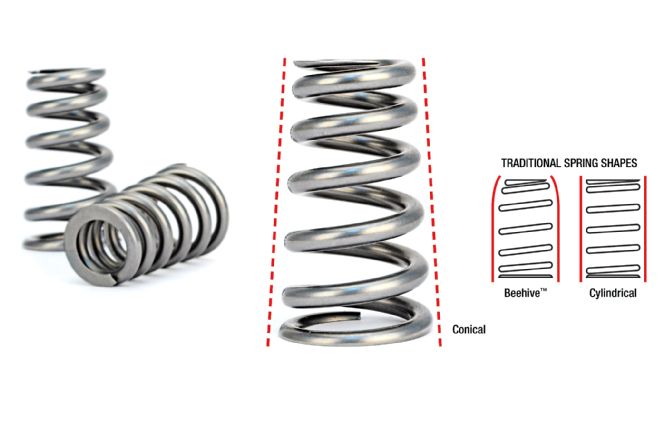

What is interesting is that the real improvement for this valvespring comes from simple geometry. Just like it is named, the spring is shaped like a cone with each coil on a continuous decreasing radius. At first you may think it is just another way to use a smaller, lighter retainer on a valvespring with a larger base much like the beehives that Comp has had for a while now, but there is a very critical difference.

Before we can get to that difference we have to discuss the Achilles heel of the modern performance valvespring. Today wire technology and the manufacturing process is so advanced that getting enough spring pressure and building valves that can survive a super-aggressive cam is now quite possible. What still causes problems is harmonic vibrations that can degrade the spring’s ability to control the valve and, in turn, destroy engines.

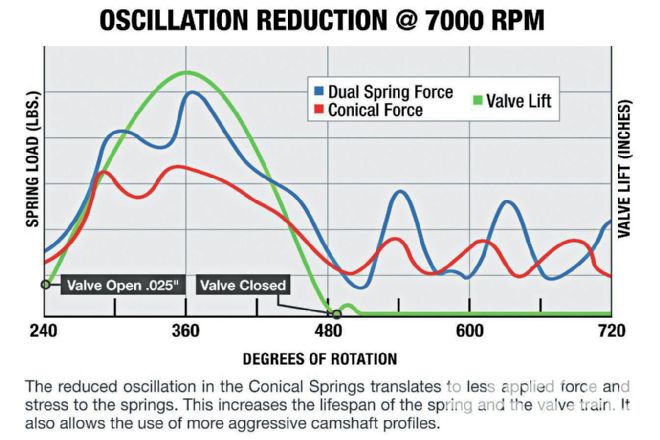

Almost all current generation valvesprings will have a point in the rpm range where the rate at which the spring is compressed and allowed to expand matches its natural frequency. When this happens the spring’s oscillations feed upon themselves and grow out of control. When this happens, valve control quickly goes out the window. Because you can’t get around that point, the only solution engine builders have is to band-aid the problem by trying to find a spring that has a natural frequency above or below the rpm range the engine will see on the track.

But the conical valvespring design is very different. Because each coil on the spring is different from every other coil on the spring, every coil has its own natural frequency. It is impossible for the spring as a whole to fall into a harmonic state because when one coil hits its natural frequency, the other coils will serve to dampen the oscillation. When the engine moves out of that rpm range, that particular coil moves out of its harmonic state and becomes a damper for the next coil that reaches its natural frequency.

This isn’t just academic; Comp’s Billy Godbold says they’ve seen the damping effect of the conical spring in testing. “What really shocked us with the conical design once we got the right aspect ratio—the top-to-bottom pitch—once we got that conical shape right the damping between all the coils was so much better,” he explains. “If you put a load cell on all these other (traditional) springs, you see that they go through clash modes every couple hundred rpm. But when we repeated the tests with the conical valvesprings we couldn’t get the springs to show these load spikes.”

A conical valvespring may look a lot like a beehive, but they are quite different. A beehive spring has a consistent coil diameter until you get to the last few coils at the top. But every coil on a conical spring has a different diameter, so when one coil goes into resonance the other coils acct as a natural damper to help keep the spring under control.

A conical valvespring may look a lot like a beehive, but they are quite different. A beehive spring has a consistent coil diameter until you get to the last few coils at the top. But every coil on a conical spring has a different diameter, so when one coil goes into resonance the other coils acct as a natural damper to help keep the spring under control.

For engine builders, this self-damping phenomenon that takes place thanks to the specific coil geometry Comp developed has two significant real-world benefits. First, given the very same engine package, the conical spring is much less likely to break than either a straight barrel spring or a beehive spring. Godbold says that because the spring doesn’t have a natural resonance it simply doesn’t see the stresses that a traditional spring does. When a valvespring reaches its natural frequency, it can no longer provide enough pressure to adequately pull the valve back toward the seat and, as a result, the entire valvetrain can go out of control. Besides a loss in power, this is also quite damaging to valvetrain components. For example, if the spring allows the valve to float, that creates a gap between the tip of the valvestem and the end of the rocker arm. When the spring finally catches back up, it sends the valvestem crashing back into the rocker arm with damaging force. Loss of spring pressure can also allow the valve to bounce, which destroys both the valve and the seat. Finally, it’s all that uncontrolled movement that’s also the cause of many valvespring failures.

Second, when the conical springs are properly matched to the valvetrain they can significantly increase the engine’s rpm redline. “The conical spring can get by with a lot less spring pressure than a standard straight spring because the reduced diameter at the top, as well as the smaller retainer required, significantly cuts down on the mass at the top of the spring that’s moving up and down,” Godbold explains. “In that respect they are a lot like our beehive springs. And beehive springs have been around long enough now that most engine builders will have a good idea what spring pressure works for their engine package.

“Where the conical spring really separates itself from the beehive is the beehive still exhibits some resonance and you have to get around that is by putting too much spring on the engine—which is really just a crutch. Where I’ve been really impressed with the conical spring is we’ve done tests with engines where we have taken off the beehive spring, installed a conical spring with the same open and seat pressures and instantly raised the engine’s maximum speed by four- or five-hundred rpm.

“With the beehives springs, they would hit their natural resonance rpm and they couldn’t get through it. They may have had more left, but because of the loss of valve control when the springs were in resonance, the engine isn’t operating as efficiently as it should, so it loses power and it can push past that rpm. So with the conical we are seeing the rpm limits go up considerably more.”

Even if you are already past peak power, a higher redline means you can put more gear in your car and gain a mechanical advantage on the rest of the field. More rpm means the car is also less likely to “lay down” halfway down the straight.

We are eager to put Comp’s new conical springs to the test to see for ourselves just how much can be gained both on the dyno and the racetrack. This is just a preliminary look at an emerging technology; stay tuned as we see just how far this new spring design can be pushed in future issues of Circle Track.