Experience has taught us the significance of the phrase, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” After all, why tear into a well-running Pontiac V-8 to install a new camshaft or cylinder heads if the performance with the existing components meets or exceeds the expectation? Our thinking is unless the changes will drastically improve performance or driveability, we’d rather leave the entire combination alone and sideline any major changes until the engine requires other attention. At that point, we can then execute a master plan and apply the most modern rebuild techniques and use the most modern components reasonably possible.

Our ’72 Trans Am is a perfect example of this approach. We purchased it in 1987, and, shortly before taking possession, its original 455 H.O. mill had been professionally rebuilt. It performed so satisfactorily that there wasn’t ever a need for it to come out or apart.

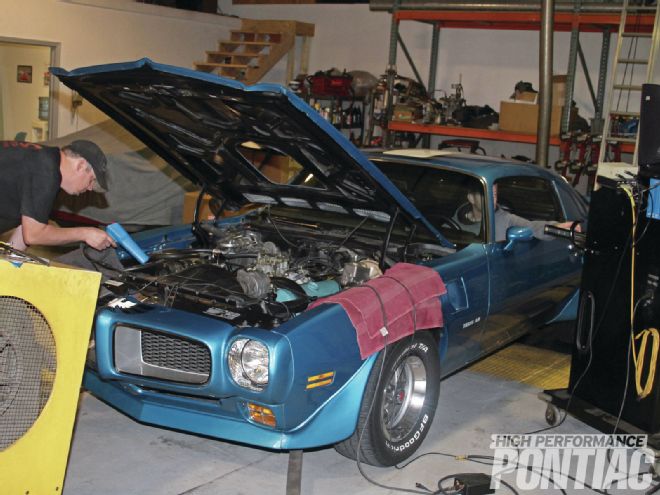

1 Rebuilt just prior to our purchase in 1987, the 455 H.O. performed excellently for the 25 years it was in service; so much so that we had no qualms about thoroughly flogging it on the chassis dyno, making several full-throttle pulls to 5,500 rpm to find peak power months earlier. When considering driveline loss for that particular dyno, the 455 H.O. was producing about 330 hp and 415 ft-lb at the crankshaft—reasonable numbers considering the combination and components used. "> <strong>1</strong> Rebuilt just prior to our purchase in 1987, the 455 H.O. performed excellently for the 25 years it was in service; so much so that we had no qualms about thoroughly flogging it on the chassis dyno, making several full-throttle pulls to 5,500 rpm to find peak power months earlier. When considering driveline loss for that particular dyno, the 455 H.O. was producing about 330 hp and 415 ft-lb at the crankshaft—reasonable numbers considering the combination and components used.

<strong>1</strong> Rebuilt just prior to our purchase in 1987, the 455 H.O. performed excellently for the 25 years it was in service; so much so that we had no qualms about thoroughly flogging it on the chassis dyno, making several full-throttle pulls to 5,500 rpm to find peak power months earlier. When considering driveline loss for that particular dyno, the 455 H.O. was producing about 330 hp and 415 ft-lb at the crankshaft—reasonable numbers considering the combination and components used.

Recently, however, finding a coolant puddle beneath it was very concerning. Once we determined a leaky frost plug as the source, we knew the engine had to come out for the first time since 1986. It would also give us an excuse to freshen up its external appearance, but we quickly found ourselves amid a complete rebuild. Here’s why.

Setting The Stage

Our 455 H.O. was rebuilt during the mid-’80s and the seller disclosed all he knew about it at the time of the sale. Its numbers-matching block was bored 0.030-inch, and the connecting rod and main journals of the original nodular-iron crankshaft were undersized by 0.010 inch each. Cast rods were reconditioned and stock-replacement cast pistons were hung from them. The 7F6 Round-Port cylinder heads were treated to a three-angle valve job, but were otherwise left untouched. Its compression ratio worked out to approximately 8.5:1.

During that rebuild, a hydraulic flat-tappet camshaft, much like an original R/A-IV grind, was installed. The combination ran exceptionally well at full throttle, but the lumpy aftermarket cam was cold-blooded and caused driveability to suffer. It proved too much for the Turbo 400 with a stock-stall torque converter and the 3.08 rear-axle ratio. Nunzi’s Automotive recommended its 2041NHL grind, which we had installed by a Pontiac dealership technician.

With a well-chosen cam, which complemented the entire combination in place, the engine idled and operated at lower speeds much better and full-throttle performance seemed just as strong. For the next two decades, the 455 H.O. continued to perform as well as ever. Small modifications like the addition of roller rocker arms, carburetor, and distributor tuning yielded noticeable improvements, but over the course of the 10,000 miles we drove it, it was so reliable that, beyond regular maintenance, we otherwise never had to turn a wrench on it.

We were so confident in its ability, we spent the better part of a day in 2010 flogging the 455 H.O. on a chassis dyno to measure output and determine the most optimal tune. The best recorded output that day was 264 rwhp and 330 rwtq (the details were shared in “Dyno-Mite!,” HPP, April ’11). Happy that it was performing as well as it could, we enjoyed the Trans Am even more every time it was on the road.

Issues Begin To Surface

Then things began to change. A quick visual inspection to trace a minor oil leak revealed that it was coming from the crankshaft seal located in the front cover. When we prepared to remove the harmonic balancer and drive in a new seal, we noticed the balancer bolt was reasonably tight, but not at the factory torque spec of 160 ft-lb.

Short of loosening up over the years, it seemed more reasonable that it simply wasn’t torqued properly when the technician installed the new camshaft for us some 25 years earlier. Upon removing the balancer, it no longer fit snugly on the crankshaft keyway, and that meant a new balancer was in order. We replaced the seal, installed the new balancer, torqued its bolt to 160 ft-lb, and the Trans Am was back on the road, but not for long!

After an hour-long highway cruise on a lazy Saturday afternoon, we parked the Trans Am in the garage and a significant puddle of coolant soon appeared beneath it from the center frost plug on the passenger side of the block. Because the plug was located directly behind the engine mount, the only way to access it for repair was to pull the engine.

Removing the 455 H.O. from the T/A went exactly according to plan. Once fastened to an engine stand, we quickly identified the leaky frost plug, which was in very poor condition, and we found two others in similar shape. It became apparent that we had dodged a major catastrophe. Had any of those let go while out cruising, it would have made a mess of the engine compartment and left us stranded on the side of the road waiting for assistance!

While the engine was out, we planned to replace the oil pan, which had its own issue, and paint the 455 H.O. in the correct shade of ’72 Pontiac engine blue. We thought the process was going to be simple. Then we began to find a host of other issues during disassembly. Check out the captions and photos for the details.

Conclusion

We sourced many new components for the 455 H.O. and injected some modern technology. What’s simply amazing is how well this engine performed even with the issues it contained. If it wasn’t for the leaky coolant plug, we may have never had the chance to catch any of the underlying concerns before they became major problems.

So just how well did the 455 H.O. perform after the complete rebuild? In next month’s issue, we’ll discuss exactly that!