The idea was simple enough. Over the last two years, we've been comparison testing budget-oriented small-block Chevy parts. You probably recall all those chart-infested single- and dual-plane intake (nearly 50!), cylinder head, and carburetor tests. We evaluated these parts based on multiple categories. We looked at peak horsepower, average torque, and horsepower-per-dollar—the classic "bang-for-your-buck" quotient. Once we had completed mashing all these tests through the CC wringer, we realized that if we assembled an engine with all the best parts, we might have a great street small-block. Thus, our Quick Draw engine was born.

It may be “just another small-block Chevy,” but to us it’s our Quick Draw .357. It not only made good power, but you don’t have to spend next year’s rent budget to build your own version of this little street engine.

It may be “just another small-block Chevy,” but to us it’s our Quick Draw .357. It not only made good power, but you don’t have to spend next year’s rent budget to build your own version of this little street engine.

For those of you who have already skipped ahead to see what heads and intake we chose, you may be mildly surprised by our choices. But before you think that we've been bought off (shame on you), at least allow us to explain the selection process. In a simpler world, the choices would be very easy—if we were looking at intake manifolds, for example, we would just choose the casting that made the best power. But in the real world of low-hood-height street cars and Kraft Mac & Cheese budgets, really good power also means really big money. If you recall, in each of these previous tests, we hammered average torque as the great qualifier. Then for the “bang-for-the-buck” quotient, we divided average torque by the cost of the component—just like any good bargain hunter. But cheapie manifolds often skew even those evaluations, so you still had to apply your own personal spin to the numbers to choose what you would consider the best of the parts. That's exactly what we did.

Foundation Work

Before we detail the all-star parts, you need to know about our test engine. We planned to use a 355ci small-block that I've had for nearly 20 years equipped with flat-top forged pistons and good 5.7-inch rods. After two decades of abuse, it developed a rather pronounced bearing knock, so it had to come apart. The cylinder walls and crank surface looked worn, so we had the crank turned 0.010 under and went with a new set of Sportsman Racing Pistons (SRP) forgings and a set of Scat 6.00-inch I-beam connecting rods. The SRP flat-top pistons use Forged Side Relief (FSR) technology to reduce the contact area of the piston to the cylinder and come with a thin 1.2-, 1.3-, and 3.0mm ring package that includes a carbon steel nitride top ring and a Napier-style second ring for better oil control. These pistons might be considered overkill for a budget street 355, but we intend to use this engine for many other parts flogs, so we needed a good, durable piston that could withstand massive dyno abuse. We matched the pistons with a set of Scat 6.00-inch connecting rods that we could spin to 7,500 rpm or more if necessary, while the father and son team at Barrington Engines performed their usual professional efforts with the 4.040 overbore and a torque plate hone. We then measured piston-to-deck height and had Barrington machine the block to bring the pistons to within 0.005 inch of zero deck. We reused our Milodon oil pan and windage tray, along with a Fel-Pro one-piece oil pan gasket and filled the pan with six quarts of Lucas Break-In oil.

Because this had to be a pump-gas–friendly engine at 10.2:1 compression, we wanted to keep the camshaft both affordable and streetable. The point of this engine is not to make blunt-force power but to assemble an affordable small-block that will make great torque with good throttle response. We found Lunati offers the Voodoo line of budget camshafts, so we picked what we felt was a good compromise between street torque and peak horsepower that would work well with the rest of the engine. We certainly could have made more power had we selected a hydraulic roller instead of this flat-tappet version, but roller cams are more expensive, so we stuck with the flat-tappet version that priced at a bit more than $200.

.357 Parts

Let's start with the big-ticket item. In our original cylinder head shootout, the selection criterion was only heads that retailed at less than $1,000. You may recall that the Patriot heads performed very well, but in the interim, the company appears to be experiencing reorganization and parts were not available, so we widened our search. The Jegs 180cc head we first tested looked attractive, but we landed instead on the 195cc version because they are only $40 more than the 180cc heads, which is a great bang-for-the-buck deal. We were tempted to step up to the 210cc heads, but that meant we would have to drop nearly $1,400, so we opted for the midsized 195cc port volume heads with the smaller, 1.25-inch-diameter single valvespring. This turned out to be a horsepower-limiting factor. More on that when we get to the testing.

Perhaps the most extensive comparison testing we did was on intake manifolds, where we ran through more than 40 single- and dual-plane versions. Since our gunslinger engine was always going to be a street engine, we focused on the dual-planes and decided that our best power-for the-pennies bet would be with the Edelbrock Performer RPM. The Air Gap makes more power, but in keeping with cash consciousness, the tried-and-true RPM got the nod. We also decided to test a single-plane just to remind ourselves why dual-plane intakes on mild street engines are the only way to go. We still had to pick a single-plane to test, so we went with Holley's Strip Dominator again because it seemed to offer good overall power and wasn't so tall that it might fit under a mild cowl hood.

Topping our 357ci All-Star test mule for the initial testing is an Edelbrock Performer RPM intake that we felt offered the best combination of horsepower, torque, and low cost. For a carburetor, we opted for that swap meet 750 0-3310-3 carb that we bought for a mere $85. We also tried a Holley 750-cfm HP carburetor just to evaluate the old versus a known good mechanical secondary carb. The HP was worth 2 extra horsepower, so we went with the vacuum carburetor for all our final numbers.

Topping our 357ci All-Star test mule for the initial testing is an Edelbrock Performer RPM intake that we felt offered the best combination of horsepower, torque, and low cost. For a carburetor, we opted for that swap meet 750 0-3310-3 carb that we bought for a mere $85. We also tried a Holley 750-cfm HP carburetor just to evaluate the old versus a known good mechanical secondary carb. The HP was worth 2 extra horsepower, so we went with the vacuum carburetor for all our final numbers.

This left us with the selection for a carburetor. Here's where the choice was really easy. If you recall, our original test was confined to vacuum secondary carburetors costing $299 or less. For fun, we also tossed in a vacuum secondary 0-3310 Holley 750-cfm carb we bought at the swap meet for $85. Of course, it didn't run when we first tried it, and it took an idle circuit roto-rooting to make it work. But once we tuned it up, it went from the doghouse to the shady spot on the front porch just beating out the new Holley 750 carb. So we brought the old dog out of retirement and planned to test our swap-meet hero against a 750-cfm HP mechanical secondary carb to see if there was any difference.

To round out our All-Star small-block, we added a set of Hedman 13⁄4-inch headers for a Chevelle and added a pair of Dyno-Max mufflers with 3-inch lead pipes to get closer to a typical street application. We retained Westech's electric water pump because it could cool the engine quicker in between runs, and we also used an MSD distributor and 6AL ignition because it plugged right into Westech's dyno ignition. We also decided to try the Voodoo 1.6:1 roller rockers. Once the cam was formally broken in by running it at various load levels for a solid 30 minutes using the Lucas SAE 30 Engine Break-In oil, we were ready to make some noise.

Instead of using Westech’s hero dyno headers, we wanted to use a set of true street car 13⁄4-inch Hedman Chevelle headers. These are great headers because they are both inexpensive, and the long collector usually helps low-speed torque.

Instead of using Westech’s hero dyno headers, we wanted to use a set of true street car 13⁄4-inch Hedman Chevelle headers. These are great headers because they are both inexpensive, and the long collector usually helps low-speed torque.

Unholstered Results

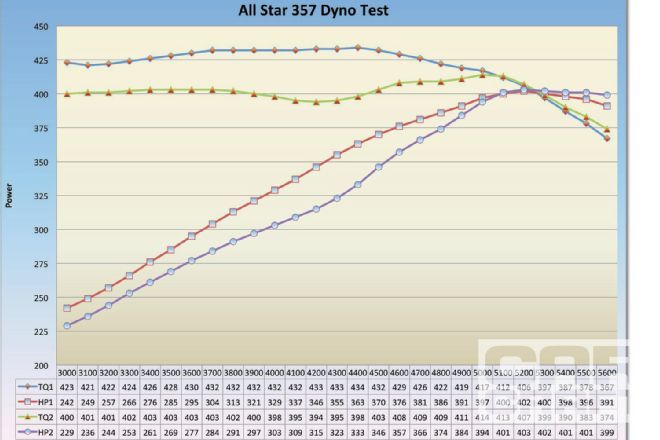

We started with the dual-plane RPM intake in place along with the swap meet 750-cfm vacuum secondary carburetor. Once we determined that this engine liked 40 degrees of total timing and an air/fuel ratio of around 12.8:1 at peak horsepower, the first pulls on the engine indicated we had a problem once the engine got around 4,600 rpm. It was clear that the small-diameter valvesprings were not able to handle the higher acceleration rate of the 1.6:1 Lunati rocker arms. Since time on the dyno was limited, we decided to go back to the standard 1.5:1 roller rocker ratio. After a little more tuning, the 357 picked up to 402 peak horsepower at 5,200 rpm with a peak torque of 434 lb-ft at 4,400. This was both good and not-so-good news. The good news was that this little engine was making more than 420 lb-ft of torque at 3,000, which means it will accelerate well even in a heavy car with an automatic and tall gears. But the peak power was certainly not as strong. We were shooting for more like 425 to 430 hp, which would be a true 1.2:1 hp per cubic inch. But looking at the graph of the power curve (page 18), it was obvious that our small valvesprings were holding us back. If you look at the torque curve, at 4,400 the curve takes a sharp downturn, which indicates that the springs were having trouble controlling the valves, causing valve bounce, which immediately begins to lose power. Our recommendation would be to go with the 195cc heads with the larger-diameter 1.440-inch valvespring or, if you have a similar problem on your engine, choose a spring similar to the spring recommended by Lunati. The Jegs head spring was rated at 100 pounds on the seat with around 300 pounds of load at the 0.525 max lift with a rate of 380 pounds per inch. A good spring like the 1.440 that Jegs offers would have a 333 lbs/in rate with 130 lbs of load on the seat and 300 lbs with the valve open. In discussing this with Steve Brulé at Westech, a dual spring with a slightly better rate could be worth an increase of peak horsepower rpm to 5,800 with perhaps as much as a 20 to 25 hp gain. This would put this engine at 430 hp at 5,800 rpm, which is what we expected. The larger spring would also allow us to return to the 1.6:1 roller rockers, which should also improve the overall power curve.

There are plenty of dual springs available that will fit the Jegs head that would work well. A fresh alternative idea is a Lunati beehive spring. For example, Lunati’s Pacaloy ovate beehive spring (PN 74818) offers 130 pounds on the seat at 1.800 and 310 pounds of load at 0.575 lift. Plus, the top of the spring is lighter for better control at high speeds. This spring package runs around $260 for springs, retainers, and locks.

There are plenty of dual springs available that will fit the Jegs head that would work well. A fresh alternative idea is a Lunati beehive spring. For example, Lunati’s Pacaloy ovate beehive spring (PN 74818) offers 130 pounds on the seat at 1.800 and 310 pounds of load at 0.575 lift. Plus, the top of the spring is lighter for better control at high speeds. This spring package runs around $260 for springs, retainers, and locks.

To eliminate variables, we also dropped on the Holley 750 HP mechanical carb for a quick carburetor evaluation. The HP offered a slightly richer fuel curve but really didn't give us any significant power increase, which just proved to us that our budget Holley 750 vacuum secondary carb was worth all the trouble to make it work.

We also tried a Holley Strip Dominator single-plane intake. We knew that a single-plane would improve the top-end power but sacrifice torque. That’s exactly what happened. As you can see by the dyno curve (page 18), losing 30-plus lb-ft of torque across a wide range makes the single-plane a singularly bad idea for this application.

We also tried a Holley Strip Dominator single-plane intake. We knew that a single-plane would improve the top-end power but sacrifice torque. That’s exactly what happened. As you can see by the dyno curve (page 18), losing 30-plus lb-ft of torque across a wide range makes the single-plane a singularly bad idea for this application.

Next, it was time to test the Holley Strip Dominator. Typically, a single-plane intake trades low-speed torque for more peak horsepower. The key is whether the trade-off will allow the car to run quicker in the quarter-mile by shifting the power curve into the higher engine speeds. With our 357ci engine, the valvesprings limited the engine's top-end potential, and unfortunately, the big single-plane really hurt the midrange power curve. As you can see by the dyno graph, at 4,200 rpm the single-plane lost 38 lb-ft of torque with a similar difference all the way through until peak horsepower, where the single-plane finally made more power. As far as this combination is concerned, the dual-plane is a far better choice. We would need bigger, higher flowing heads, and a bigger cam to justify a single-plane intake.

Perhaps the best part of this All-Star package isn't that the peak horsepower is all that impressive in these days of simple 500-plus-hp LS engines, but that we have a very simple small-block with mild heads, a budget flat-tappet cam, and pump gas compression that offers excellent midrange torque that should make a typical street car really fun to drive. In terms of quarter-mile times, we plugged the curve into our copy of the Quarter Pro simulation, and in a conservative 3,550-pound car with 3.55:1 gears and a three-speed auto with a 2,800-rpm converter, like our Orange Peel Chevelle, the program says that even with a slow 1.90 60-foot time, this engine should be capable of 12.50s at 104 mph. That's what we'd call a Quick Draw ride on a Shirley Temple budget.

To ensure we had plenty of fuel, the Westech dyno uses an Aeromotive fuel pump to ensure we had constant supply of 6.0-psi, 91-octane pump gas.

To ensure we had plenty of fuel, the Westech dyno uses an Aeromotive fuel pump to ensure we had constant supply of 6.0-psi, 91-octane pump gas.

Dyno Testing

Test 1 used the 357ci long-block, an Edelbrock Performer RPM, Holley 0-3310-3 carburetor, Hedman 1 3⁄4 inch headers with DynoMax mufflers, and a 3-inch exhaust on 91-octane pump gas.

Test 2 substituted the Holley Strip Dominator single-plane intake. All other components remained the same.

The graph reveals the major torque improvements of the dual-plane versus the single-plane intake. The curves also illustrate how even the dual-plane (TQ1) torque begins to suffer at 4,500 rpm and really tips over at 5,000 rpm. It appears that the engine experienced mild valve float at around 5,000 rpm, which is why the peak power occurred at 5,200 rpm. With stronger valve springs, this engine should push the peak horsepower to 5,800 rpm with a peak of 420 to 425 hp.

Cam Specs

Cam – PN 10120704 Dur. at 0.050 Lift (inches) Lobe Separation Intake 233 0.504 110 Exhaust 241 0.525

*Valve lift spec is with a 1.5:1 rocker ratio.

Previous Testing

This article is based on the four small-block Chevy component tests that Car Craft has performed in the last 24 months. In case you may have missed one or more of these tests, here are the issues in which these stories ran in case you might want to do your own selection for an All-Star engine. All of these stories can be found on the Car Craft website, as well.

Story Description Issue Under $1,000 Cylinder Head Test September, 2012 The Great $299 Carb Shootout October, 2012 The Great Intake Flog (single-planes) June, 2013 The Great Intake Flog, Part II (dual-planes) September, 2013

Parts List

Description PN Source Price SRP pistons, rings 279480 Summit Racing $662.16 Scat 6.0-inch connecting rods 26000716 Summit Racing $344.97 Lunati cam/lifter package 10120704LK Summit Racing $204.97 Lunati timing set 95100 Summit Racing $163.97 Lunati rockers, 1.5:1 15300-16 Summit Racing $264.97 Lunati pushrods 5062-16 Summit Racing $109.97 Jegs 195cc w/ 1.250 spring 514020 Jegs $1,109.90 Jegs 195cc w/ 1.440 spring 514030 Jegs $1,199.98* Edelbrock Perf. RPM 7101 Summit Racing $177.97 Holley Strip Dominator 300-25 Summit Racing $207.97 Holley 750 vacuum carburetor 0-3310-2 Swap meet $85 Holley 4150 conversion 34-13 Summit Racing $44.97 Holley 750 HP 0-80535-1 Summit Racing $779.97* Speed-Pro main bearings 138M-10 Summit Racing $66.99 Speed-Pro rod bearings 8-7065CH-10 Summit Racing $72.99 Durabond cam bearings CHP8 Summit Racing $23.97 Fel-Pro MLS head gasket 1142 Summit Racing $125.94 (pr.) Fel-Pro pan gasket 1885 Summit Racing $23.97 Fel-Pro intake gasket 1206 Summit Racing $14.97 Fel-Pro valve cover gasket 1628 Summit Racing $50.97 Milodon oil pan 30900 Summit Racing $179.97 Milodon oil pump 18755 Summit Racing $39.97 Milodon oil pump pickup 18311 Summit Racing $43.97 Milodon windage tray 32100 Summit Racing $31.97 ARP head bolts 134-3601 Summit Racing $80.24 ARP main cap bolts 234-5501 Summit Racing $85.91 ARP intake bolts 134-2001 Summit Racing $19.90 ARP crank bolt 134-2501 Summit Racing $23.59 MSD distributor 8361 Summit Racing $215.97 MSD plug wires 31223 Summit Racing $84.97 Hedman 13⁄4-inch headers 65101 Summit Racing $225.97 Lucas SAE 30 break-in, 5 quarts 10631-1 Summit Racing $21.97 Bosch spark plugs (8) 7958 Summit Racing $12

*These components not used in this test but included for information.