The Combo

Nothing is more frustrating than having a restored factory hot rod that just won't run the way it should. That was the problem with Eric DeRosa's supercharged '63 Studebaker Lark. As purchased by DeRosa back in 1998 in running condition, the car's original factory blower motor was long gone, replaced by a standard Stude 289 V8 engine. However, the lightweight, 3,000-pound Lark retained a bunch of its other rare options, including a Borg-Warner T10 four-speed manual trans, a 3.73:1 Dana 44 rearend with a limited-slip differential, a factory in-dash tachometer, and factory front disc brakes.

Car owner Eric DeRosa (standing) discusses the rescue of his blown ’63 Studebaker Lark with Westech’s Dave “Doc” Clarbour.

Car owner Eric DeRosa (standing) discusses the rescue of his blown ’63 Studebaker Lark with Westech’s Dave “Doc” Clarbour.

DeRosa relates, "Over the course of many years, I eventually purchased all the unique parts needed to convert the engine back to build-sheet–correct condition. When my brother, Adam, and I rebuilt the motor in 2009, we bored it 0.030-over and installed the high-performance factory cam, valves, springs, et cetera, but did not install the supercharger or the unique carb used with the blower. I ran it for a few years with a regular Edelbrock carb instead. In summer 2012, I finally put on the original Paxton supercharger and Carter AFB carb, which had been sitting on a shelf for many years. We also changed the rear gears to a more street-friendly 3.31:1. The car was rushed to completion just two days before I drove it to the big Studebaker national show, where it won a First Place award.”

Restored to “build-sheet–correct” trim, the ’63 Lark’s bodywork and Rose Mint paint are courtesy of Scott Stasney’s Deluxe Auto Werks.

Restored to “build-sheet–correct” trim, the ’63 Lark’s bodywork and Rose Mint paint are courtesy of Scott Stasney’s Deluxe Auto Werks.

The Problem

But driving it there was no fun at all. The Stude ran extremely rich from the get-go. "It bogged, stalled, and was really a handful to get down the road,” DeRosa recalls. "We switched out the metering rods to lean it out, but it wasn't enough.” Fortunately, the Libertyville, Illinois–based car was located only 30 miles away from one of our favorite fix-it shops: Norm Brandes' Westech Automotive.

Located in southern Wisconsin, Norm Brandes’ Westech Automotive has the reputation for being able to fix just about anything, early or late.

Located in southern Wisconsin, Norm Brandes’ Westech Automotive has the reputation for being able to fix just about anything, early or late.

We called the Studebaker Parts Department, but they were closed.

The Diagnosis

As received, at idle, the choke would not fully release after warm-up, even with the choke thermostat set on its leanest notch. Westech temporarily disconnected the choke so the carb's basic calibration could be cleanly dialed in on its sophisticated Mustang chassis dyno that permits steady-state speed and rpm tests at varying loads. Combined with a wideband Lambda sensor, this lets the tuner really home in on part-throttle driveability issues. With the choke factored out, 35–65-mph road-load simulations were run on the dyno to find the part-throttle cruise "sweet spot”—the leanest portion of the carburetor where the power enrichment was just coming into play. Cruising at 60 mph, a 12:1 air/fuel (A/F) ratio was observed at 11.5–12 inches of vacuum at 2,200–3,200 rpm. "This showed the overall cruise mixture was set way too rich,” explains Westech owner Norm Brandes. Further analysis revealed problems with both the ignition and carburetor.

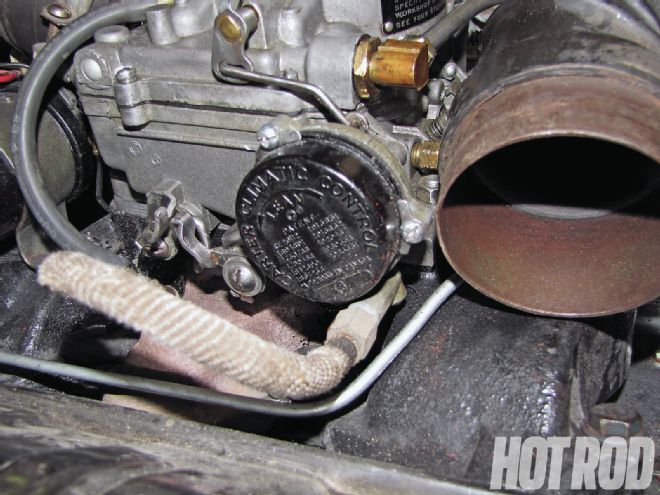

The Lark’s driveability woes were caused by over-rich primary-side carburetor calibration compounded by the wrong choke cover.

The Lark’s driveability woes were caused by over-rich primary-side carburetor calibration compounded by the wrong choke cover.

The Fix: Distributor

Westech found the old factory-installed Prestolite dual-point distributor's mechanical advance curve came in later than called for by the stock factory specs. The cause, according to Brandes, was mainly "old, coagulated grease and oil binding up the mechanism, plus a little corrosion.” A thorough clean-up and regrease got the centrifugal advance mechanism working correctly. The Westech crew also verified that the TDC marks on the balancer correctly aligned with the timing pointer at TDC, and that there was no observable balancer delamination. Ignition-coil voltage output was correct, and the point gap was on the money at 0.020 inch. Westech set the initial timing to stock specs and put the Stude back on the dyno.

Leaner primary step-up rods, a heavier step-up spring, secondary air-valve weight mods, and a new choke cover let the Stude sing like a Lark.

Leaner primary step-up rods, a heavier step-up spring, secondary air-valve weight mods, and a new choke cover let the Stude sing like a Lark.

The Fix: Clean-out

Technician "Doc” Clarbour ran the car at 3,500 rpm under moderate load and constant throttle for 20 minutes to blow any carbon buildup out of the combustion chambers. If a car is badly gummed up, the wideband oxygen sensor used for tuning purposes won't be accurate, and the car itself probably won't respond to any fine-tuning. You can do the same thing by driving down the highway at a constant 3,500 rpm for 20 minutes. The spark plugs were also decarbonized using a propane torch. After the clean out, the Stude's carb did lean out a tad, and idle quality improved, but it was still way too rich at cruise.

Dialing in the Stude required nearly a day on Westech’s high-end Mustang chassis dyno, running at various loads and throttle openings.

Dialing in the Stude required nearly a day on Westech’s high-end Mustang chassis dyno, running at various loads and throttle openings.

The Fix: Part-Throttle Cruise

Before delving into detailed carb calibration, Westech first carefully verified the old Carter AFB carb's physical integrity. Brandes explains, "We made sure there were no leaky plugs in the aluminum casting, sunk floats, or seepage past the needle and seat. The carb checked out mechanically sound."

The Carter AFB was pulled for detailed inspection. The rare model (PN 3725S) used on blown Stude 289s had sealed throttle shafts for compatibility with the blow-through induction system—you can’t just replace it with a generic late-model. Fortunately, the carb was physically OK, just miscalibrated. Yes, even on this early car, the vacuum advance connects to a ported vacuum source (arrow).

The Carter AFB was pulled for detailed inspection. The rare model (PN 3725S) used on blown Stude 289s had sealed throttle shafts for compatibility with the blow-through induction system—you can’t just replace it with a generic late-model. Fortunately, the carb was physically OK, just miscalibrated. Yes, even on this early car, the vacuum advance connects to a ported vacuum source (arrow).

Westech tuned the primary side first, calibrating for best highway-cruise economy and smooth initial tip-in enrichment characteristics prior to secondary opening. On the Carter AFB carb, step-up (metering) rods and main jets regulate primary-side fuel metering. Because each rod rises out of the primary jet orifice as the throttle blades open further and engine vacuum decreases, thinner (smaller od) rod tips richen the fuel curve.

The familiar Holley-style carbs use a power valve for auxiliary fuel enrichment under load. The AFB equivalent is step-up springs located under the step-up rods' pistons. The stiffer the spring, the quicker it overcomes vacuum and allows the rod to pull up out of the jet orifice. In other words, a stiffer spring actuates a primary metering rod at a higher engine vacuum point than a softer spring.

As received, the Studebaker had rich (thin) primary rods, large-orifice primary main jets, and very soft springs, a setup bound to produce an over-rich condition under daily-driving conditions. For best part-throttle driveability and fuel economy with a mild cam that generates reasonably high vacuum numbers, Westech Automotive recommends just the opposite: Install leaner (thicker) rods to achieve the best steady-state, safe, lean A/F cruise ratio, then bring the power-enrichment circuit in quicker with a stiffer step-up spring to ensure adequate enrichment under increasing load. Wide-open-throttle (WOT) performance would only be evaluated once the part-throttle cruise issues were thoroughly sorted out.

Carbon had begun to foul the Stude’s relatively fresh spark plugs. Westech didn’t want to install brand-new plugs until the carb was sorted out, but on the other hand didn’t want fouled plugs biasing the tune-up, so a propane torch was used to melt the carbon deposits off the existing plugs. Post tune-up, the plugs were changed out for a fresh set of Champion J12YCs.

Carbon had begun to foul the Stude’s relatively fresh spark plugs. Westech didn’t want to install brand-new plugs until the carb was sorted out, but on the other hand didn’t want fouled plugs biasing the tune-up, so a propane torch was used to melt the carbon deposits off the existing plugs. Post tune-up, the plugs were changed out for a fresh set of Champion J12YCs.

Old carbureted cars often have imperfect fuel distribution. Some cylinders inevitably run slightly richer or leaner than the collective average A/F ratio, as checked at the tailpipe. To ensure a safety margin, Westech says it's better to tune the old classics to a slightly richer 14.3–14.5:1 cruise A/F ratio instead of the stoichiometric 14.7:1 ratio typically preferred for late-models. This also helps compensate for today's oxygenated fuels.

After additional road-load testing on Westech's Mustang dyno at 60, 65, and 75 mph, Clarbour determined that the primary side needed to be about 20 percent leaner. That big a change requires changing the jets as well as the rods. Fortunately, the Studebaker's original AFB metering rods are the same length and have two steps just like Edelbrock's modern versions. Note that some other original factory AFB carbs may have different-length rods and/or three-step rods that won't interchange with Edelbrock parts. The jets interchange all the way through.

Currently available Edelbrock rods and jets limited the closest achievable real-world lean-out to about 17 percent. Still, that was close enough to put the A/F ratio about where it needed to be under constant-load, part-throttle conditions. But (as predicted), initial power enrichment under load suffered because of the soft step-up springs. The cure was replacing the as-received blue springs that open at 3 in. Hg with stiffer silver springs that open at 8 in. Hg.

Results

Cold start, idle quality, and cruise performance were significantly improved. However, WOT performance remains limited by the ailing supercharger that's only generating 3 psi of boost when even in its stock factory trim it should be making 5–6 psi. Owner DeRosa is satisfied that the idle and part-throttle problems he brought the car in for are solved: "It runs a lot better. I can actually start and drive the car every day now. But it still needs a few things. After driving the car for a few months, I've temporarily parked it and sent the supercharger out to be rebuilt. When I get it back on, I'll see if Westech can find the parts to fix the belt-tensioner problem while maintaining its original appearance." Once the blower is making more boost, the carb's WOT calibration and total ignition advance may need re-evaluation as well.

Lessons Learned

Old, vintage cars can be hard to fix because the chain of parts accountability—"what fits what"—has been lost over the years, as is the case with the Studebaker's choke. Fixing one problem can also reveal another, previously undetected problem, as in the case of the tired blower and its slipping drivebelt. Brandes sums it all up best: "Fixing these old cars is sometimes like peeling back the layers of an onion."