On the one hand, it is admirable that racing series attempt to contain costs for racers by maintaining consistency year after year. After all, throwing away perfectly good racing components and replacing them with equally good—but slightly different—racing components sounds a lot like a plan Congress would come up with.

But sometimes the "If it ain't broke, don't fix it" philosophy can keep people from experimenting in order to find improvements. Here at Circle Track we're big fans of making things better. You might even call it tinkering. We've set our sights on building a better race engine, and we thought we'd let you in on it.

Engine builder Bob Cronin of CRD Engine Development test fits the Lunati crank in our RHS LS Race block for our experimental next generation Super Late Model dirt race engine.

Engine builder Bob Cronin of CRD Engine Development test fits the Lunati crank in our RHS LS Race block for our experimental next generation Super Late Model dirt race engine.

GM's LS series of engines have been around for decades now and are commonly considered the go-to powerplant of choice for everyone from sports car racers, hot rodders and basically anyone who wants to make lots of power without a lot of fuss. Heck, drifters are even ditching their turbocharged four-cylinder engines and sneaking LS engines into their imports. Yes, they are that popular.

But so far they aren't very common in circle track racing. While NASCAR has created an LS "Spec" engine and there's also the "A4MP" Sprint Car engine package (the acronym stands for Alternative 410 Motor Program), nothing has really caught on big yet. And that's despite the fact that almost all major engine parts manufacturers for traditional stock car racing engines also have performance components for the LS engines as well.

So we decided to take a closer look at just what could be done by creating an LS for stock car racing purposes. And if we're going to do that, we might as well go big, right? So our goal is an LS capable of racing toe-to-toe with the current competition in one of the most horsepower-hungry classes anywhere: Super Dirt Late Model.

The rulebook for the Super classes is notoriously thin. The thinking is that practically anything goes, the limiter in the equation will be the tire. And as a result, we've seen a lot of high-end engine tech hit the racetrack in this class. Cylinder heads that have to spend hours being welded up before the porter can make radical changes to the ports, chambers and even the valve locations, billet heads, and specialty blocks with the bore spacing stretched to 4.500 inches (versus the small-block standard of 4.400) are becoming the norm. So are SB2 race engines right out of Cup shops with the addition of an aluminum block and even bigger carburetor.

We all love watching the big names in dirt racing going at it in the big events, and there's big money to be had for winning some races. But really, does this type of arms race make sense for the regular guy in dirt racing when the average payout in a Super race is seven grand or less for the winner and considerably less for everyone else?

So our plan was to put together an engine with power that was right in line with what is currently racing right now but uses affordable components that are readily available from trusted racing resources, is easy to maintain and capable of handling lots of abuse. After all, we don't want to put an engine package out there that instantly makes every other engine in the class uncompetitive and obsolete. Instead, we want to propose an engine package that can be phased in over time. So if a Super Dirt team has too much money invested in its current engine, the team can continue racing it until it's ready for the new design without being out to lunch on the racetrack.

The first step was to find the right engine builder to work with. After all, learning the hard way is fine and all, but skipping the mistakes and moving right on to the good stuff is even better. The best choice for this particular project was obvious, Bob Cronin, owner of CRD Engine Development in Concord, North Carolina, because his expertise bridges both disciplines. He's built winning traditional dirt track engines but has also had quite a bit of success with LS race motors. In fact, CRD built the engine used to win the 2005 24 Hours of Daytona. His LS engines have also won the Daytona Prototype season-long championships in 2005, 2007, and 2009. So you'd better believe Cronin and his crew know what they are doing when it comes to making reliable LS power.

"The LS motor has a few key differences from the traditional small-block that give it a real advantage when it comes to building race engines," Cronin says. "First of all, the designers fixed the heads and gave them ports that really flow a lot of air. And they've made it easy to build an engine with a lot of cubic inches. And we all know the easiest way to make power is to add cubic inches.

13. The LS7 heads are set up for a shaft-mounted rocker system. We don’t have them in yet, but we’re working with Jesel for a lightweight set of high ratio steel rocker arms.

13. The LS7 heads are set up for a shaft-mounted rocker system. We don’t have them in yet, but we’re working with Jesel for a lightweight set of high ratio steel rocker arms.

"I've built a lot of LS engines for a lot of different classes and purposes," he continues, "and while I don't know exactly how much this engine will cost, generally you can build an LS engine with equivalent power to a Chevy SB2 race motor for about 60 to 70 percent of the cost."

Once we sat down with Cronin, he quickly helped us fill out the plan. While the stock LS block can be quite adequate for many racing classes, Cronin ruled it out for a Super motor. He says he's built race motors using stock blocks that have reliable handled 730 horsepower, but they required new cylinder sleeves, which is a big cost increase, and that still isn't enough to handle the 750-plus horsepower we're looking for in part one of this build. (Ed. Note—This build will have multiple stages beginning with this phase and eventually ending with something utterly outrageous.) Instead, we decided to use RHS's excellent LS Aluminum Race Block. "The RHS block is structurally impressive, and it's obvious that a lot of thought went into its design," Cronin says.

Besides simple strength—which is always a big priority—the RHS block also includes several upgrades that make it a great choice for racing applications. First, the cam tunnel is raised so that you can squeeze in a crank with up to 4.600 inches of stroke, and when you combine that with a bore that can be as large as 4.165 inches you can produce a total engine displacement as high as 500 cubic inches. There's also a priority main oiling system that ensures plenty of oil pressure around the rod and main bearings, along with other features.

14. Raised intake and exhaust ports improve flow by creating a straight line from the port to the valve.

14. Raised intake and exhaust ports improve flow by creating a straight line from the port to the valve.

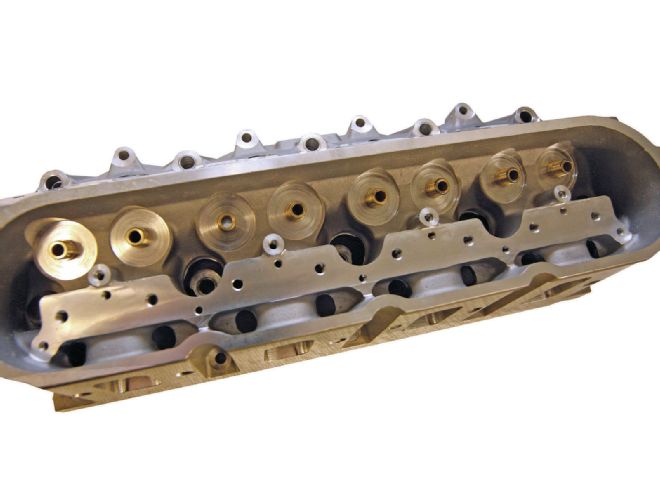

To go with them, RHS also sent over a set of their Pro Elite CNC-ported LS7 cylinder heads which should help provide plenty of raceable power. The best part is these are shelf-stock items. RHS says they keep these items in inventory and ship them out all day long, so neither the block or heads is exotic or even expensive. The block can be had for under five grand and the heads are shipped bare for just over $1,100. And that's RHS's list price, we've seen speed parts retailers selling them for less.

We're still working with manufacturers to sort out the best parts that meet our criteria for this next-generation racing engine. For example, as this went to press Mahle had one of our cylinder heads so it could digitize the combustion chamber and design a domed piston specifically for this head that brings up the compression ratio while also maximizing the fuel burn rate. The good news is we aren't keeping any secrets here, so once the pistons are ready we'll share the part number so that anyone who wants to can order up a set. All the design work and testing will already be done and you can just order ‘em up and go. You're welcome.

So with that we thought we'd share where we are in our plans, what parts we've chosen and why. Although they share many similarities, there are still lots of differences between the classic small-block Chevy and the LS engine family. Stay tuned as we continue this build with the help of Cronin and CRD Engine Development.