Jeff Scocia Asks...

I have a '66 Chevy II with a 355 with Vortec heads, a Comp 292 cam, a Performer RPM intake, a 650-cfm Proform carb, and an HEI distributor. The timing is set at about 19 degrees initial, with 32 degrees total at 2,500 rpm. It has an automatic trans with a 2,200-rpm stall-speed converter. Output was 321 hp and 400 lb-ft of torque at the rear wheels. I want to put a nitrous kit on but know nothing about it. I'm looking for a 125–150hp gain. Do I have to retard the timing? What is the best way to go? What other things do I need to watch out for?

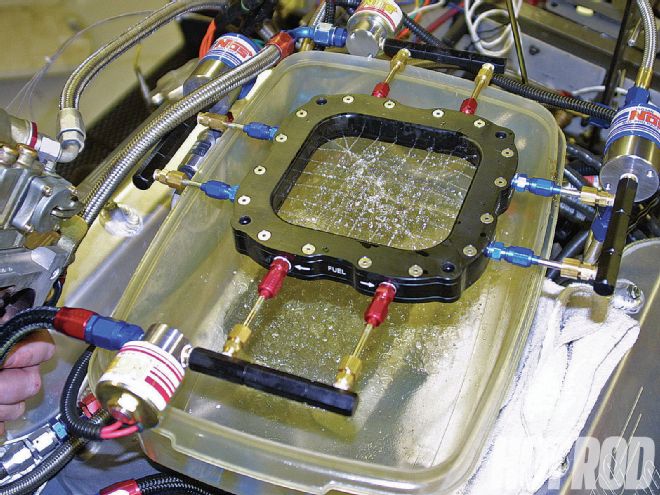

Broadly speaking, when contemplating the installation of a nitrous-oxide system, there are four main things you need to consider: the overall strength and condition of the engine's internal components, the fuel-supply system, the primary electrical system and wiring, and the ignition system. Undercarb, plate-style, nitrous kits through the 150hp range are considered to be entry-level power-adders for a small-block V8. These kits are available from all leading aftermarket nitrous-oxide companies; examples include Nitrous Oxide Systems' Sniper kits, Nitrous Pro-Flow's single-stage plate kit, Nitrous Supply's Sportstar kit, and ZEX's Perimeter Plate kit. These and similar setups are designed to install with minimal required modifications to an existing production-based V8 engine in good condition. No internal engine upgrades should be necessary at or below the 150hp power-adder threshold. With an entry-level nitrous kit, Nitrous Oxide Systems says the fuel pump needs to maintain between 4.5 and 7 psi of pressure with a flow rate of 0.1 gallons per horsepower at 6 psi. For example, adding a 150hp nitrous shot to an engine that produces 350 hp at the flywheel (for a total of 500 flywheel hp with the nitrous engaged) requires a fuel pump that flows at least 50 gallons per hour at 6 psi:

(350 hp + 150hp shot) × 0.1 = 50 gph

Most performance fuel pumps easily meet this criterion, but if you still have a stock pump of unknown origin, test it beforehand. Also, permanently plumb a fuel-pressure gauge into the system and carefully monitor it. Personally, I would prefer a 100 percent safety margin; in this case, a pump capable of flowing 100 gph. And run gas with 91 octane or better. Your HEI distributor should be adequate at this level. Do not run an old-school, stock points ignition setup. Combustion-chamber temperatures increase with nitrous oxide. To compensate, the spark plugs should be one to two heat ranges colder. Run standard-gap plugs instead of the special wide-gap plugs often specified for stock GM HEI applications. To prevent misfire, gap the standard-gap plugs to 0.030 to 0.035 inch (tighter is better). Consider standard-tip plugs in lieu of projected-tip plugs. As for ignition advance, the rule for a mostly street-driven car is to retard total timing 2 to 2.5 degrees per every nitrous-generated 50hp increase. For example, if you run 32 degrees total now with no power-adder, with a 150hp nitrous shot, pull the timing back by 6 to 7.5 degrees for a total advance in this case of 24.5 to 26 degrees:

32o - [(2o to 2.5o retard) / (50hp nitrous shot)] x 150hp nitrous shot = 24.5o to 26o

Besides ignition and electrical demands, you need to pay attention to the demands of the system's solenoids and relays, aka the "primary" electrical system. If it's necessary to extend wire length beyond that offered in the kit, move to the next thicker wire-gauge size (for example, if the kit came with 14-gauge wire, and you have to lengthen the wires, use at least 12-gauge). Don't skimp on wire quality, terminals, and splices. Don't rely on cheap butt connectors; instead, solder and cover with shrink tubing. Pay careful attention to ground integrity.

Don't forget--and this goes for any nitrous system, be it entry-level or full-competition-- N2O isn't a crutch that bulks up otherwise weak engines or marginal tuneups; it only magnifies existing problems. Get the engine running right on the motor alone before hitting the bottle, then dial in the nitrous oxide on one of your chosen kit's recommended lower-power tuneups. If it doesn't perform as it should, don't step up to the next level until you've sorted out any existing problems. Change only one thing at a time. Learn how to read spark plugs--they can tell you a lot about what the engine likes. Don't be afraid to ask fellow racers or your system's tech-support personnel for help.

Finally, don't fall victim to More's Law (the fallacy that if a little "something" is good, more of that "something" has just gotta be better yet). Once the system is dialed in and running well at the 150hp power-shot level, you'll be tempted to turn the wick up even further (many of today's single-stage plate systems can, in theory, support up to 300 hp). But nitrous shots that approach or exceed the 250hp range usually require a range of additional upgrades; at that level, you need to consider stronger internal engine parts, premium aftermarket ignition upgrades, and even a separate auxiliary fuel-supply system.

There are a number of wrecking yards and restoration companies that specialize in vintage and classic cars. Antique Auto Parts--a classic-car salvage yard--is located in West Virginia, about two hours away from your hometown. Other big, out-of-state yards include Collectors' Choice and CTC's Auto Ranch. Wildcat Auto Wrecking is one of the largest all-Mopar yards around. R/M Restoration specializes in Chrysler restoration parts, and offers a locator service for hard-to-find Mopar parts as well. And don't overlook Year One down in Georgia, one of the largest N.O.S. and reproduction parts vendors in the country.