For the 2011 Road Tour Chevy, Ron Shaver poked and stroked a 409 resulting in 474 ci. Fuel was fed by a FAST EFI system.

For the 2011 Road Tour Chevy, Ron Shaver poked and stroked a 409 resulting in 474 ci. Fuel was fed by a FAST EFI system.

When Chevrolet introduced the 265 V-8 in 1955 it was truly revolutionary. It was the little engine that could and set performance standards that all other engines would be measured by. But while the public went nuts over the new small-block, the engineers inside GM had some concerns. As good as the new engine was it did have some limitations on displacement and low-end torque. Chevy needed an engine that could not only haul around the heavier cars that were on the horizon but could be used in trucks as well.

Another W-motor from Shaver, once a 348 it now displaces 440 ci.

Another W-motor from Shaver, once a 348 it now displaces 440 ci.

While the 348/409 series are often thought to be called W engines because of the shape of the valve covers, the designation actually came from GM engineers. To find a powerplant that would meet their future needs Chevrolet began working on several new configurations, which during testing were identified as engines W, X, and Y. The X and Y engines were the larger displacement versions of the 265; the W used a new block and heads and was larger and 110 pounds heavier. Ultimately, the W design was chosen and the letter designation stuck.

One of the most unusual features of the W-series engines can be found under the heads. Rather than conventional combustion chambers in the heads, these engines have them in the cylinders. The decks of the blocks are at a 74-degree angle to the centerline of the cylinders, that, coupled with an angled crown on the pistons, results is the W’s unique combustion chambers. (It should be noted that some marine and truck engines had small combustion chambers in the heads due to lower compression.)

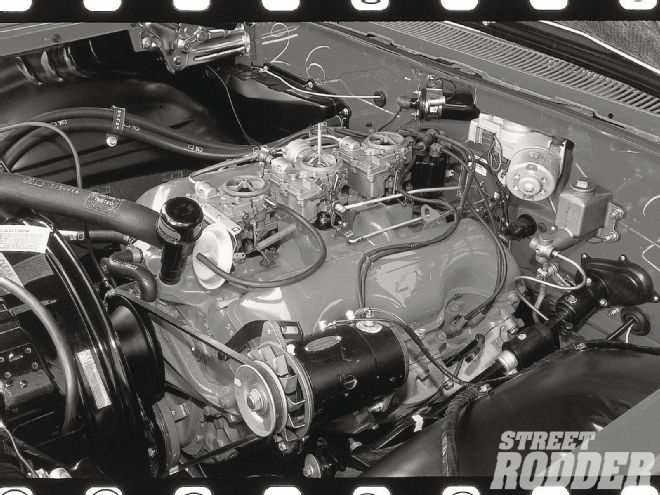

The highest horsepower 348s were equipped with a trio of two-barrel Rochester carburetors. Lower horse options had single four-barrels.

The highest horsepower 348s were equipped with a trio of two-barrel Rochester carburetors. Lower horse options had single four-barrels.

One of the advantages to the W’s combustion chamber design was the turbulence created and the resulting fast moving flame front. This created an engine that had lots of low-end torque and was resistant to detonation—two qualities that made these engines suited to use in heavy cars and trucks.

Like its smaller brethren, the W engines used tubular pushrods and stud-mounted rockers, and the blocks were cast iron with two-bolt main caps. A departure from the small-block design, oil was delivered to the mains by a gallery running low in the block on the left side. Of course the W’s most identifiable features are the scalloped rocker covers. The 348

The W-series engines were first introduced in October 1957 for the ’58 model year. They had a bore of 4.125 inches and a stroke of 3.25 inches, and were available in cars through 1961 and trucks through 1964.

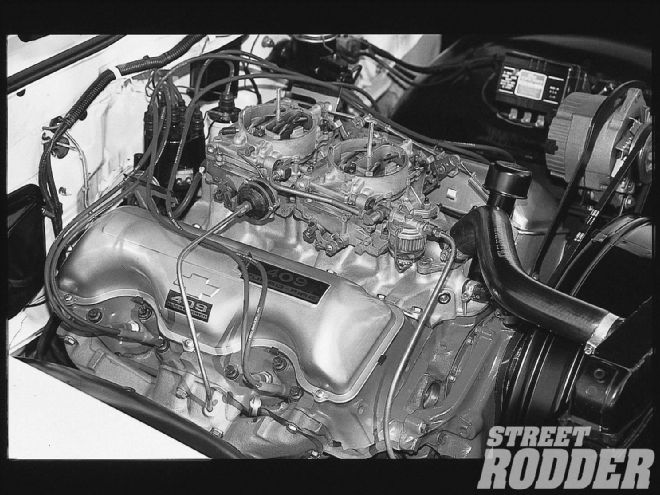

Multiple carbs in the form of dual Carter AFBs were also found on the highest horsepower 409s. Three-twos were never used on factory 409s.

Multiple carbs in the form of dual Carter AFBs were also found on the highest horsepower 409s. Three-twos were never used on factory 409s.

When introduced the base 348 was called the Turbo-Thrust and produced 250 hp, the Super Turbo-Thrust with three two-barrel carburetors was rated at 280 hp. Late in 1958, the Special Turbo-Thrust with a single four-barrel was rated at 305 horses and there was more to come. For 1959 and 1960, horsepower rose to 320, and 335 for the Carter AFB-equipped four-barrel version and three-deuce edition, respectively. Then in 1961, horsepower was bumped to 340 with a single four-barrel, and 350 with Tri-power. The 409

The 409 was introduced at the end of 1961. With a bore of 4.3125 inches and a stroke of 3.5 inches it had a solid lifter cam, a single Carter AFB, and was rated at 360 hp. Due to the late introduction, there were just 142 Impala SS 409 cars produced, making them very rare.

In 1962 the base version of the 409 produced 360 hp with a single Carter AFB, it was later increased to 380 horses, still with a single four-barrel. With the introduction of twin AFBs, better heads, and a more aggressive cam, the 409 grew to 409 hp. Thanks in part to the Beach Boys October release, everyone was singing the praises of the 409.

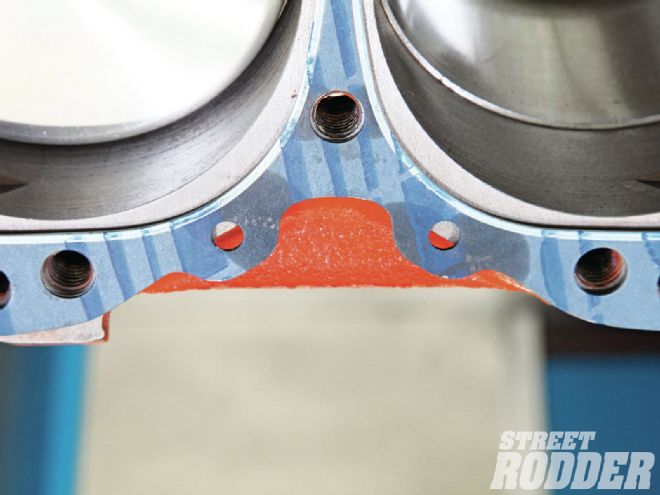

Early ’58 blocks are unusual in several respects. This is what the areas at the bottoms of the decks between cylinders 3 and 5, 4 and 6 look like.

Early ’58 blocks are unusual in several respects. This is what the areas at the bottoms of the decks between cylinders 3 and 5, 4 and 6 look like.

By 1963 there were three versions of the 409: the 340 horse with a single four-barrel and a hydraulic cam, the 400 horse with a single carb and a solid lifter cam, and the 425 hp with 11.25:1 compression, solid lifters, and two four-barrels.

The 409s available for 1964 remained the same as the previous year, however the 425-horse version would be discontinued at the end of the production run. For 1965 only, the 340- and the 400-horse 409s were available, and by mid-year the engine had been replaced with the 396. The 427 (Z11)

A special version of the 409 engine was available from Chevrolet as part of Regular Production Option (RPO) Z11. A factory creation for drag racers, it included an aluminum 427ci engine based on the W design with a longer stroke, high-rise two-piece aluminum intake manifold, and dual Carter AFB carbs. With a 13.5:1 compression ratio and a wild solid lifter cam the engine had a ridiculously low rating of 430 hp. Telling Them Apart

The same area of later 348 and all 409 blocks. The additional holes in the deck supply passages in the heads that surround the spark plugs with coolant.

The same area of later 348 and all 409 blocks. The additional holes in the deck supply passages in the heads that surround the spark plugs with coolant.

There are a few visual differences that distinguish a 348 from a 409. The most obvious is the dipstick location. The 348 has it on the left, or driver side; the 409 has it on the right, or passenger side. However, since the pans are interchangeable, it’s a simple matter to make one look like the other.

Another telltale indicator is the crankshaft flange. All Ws had a forged crank; the 348 had a round flywheel flange and the 409 was D-shaped.

Of course for absolute identification the casting numbers are the best. They can be found on the back of the block behind the left head and can be researched on several Internet sites. Shaver Builds Them Both

The Shaver family has been invoiced in racing since the ’30s when Offenhauser racing engines came to them for manufacturing and machining services. In 1976, Ron Shaver began engine development for his first sprint car engine built for Tom Hunt of Hunt Magnetos. Since then Shaver Racing Engines has grown to one of the premier race engine builders with the most advanced equipment and testing facilities around. He and his Shaver Racing Engine teams have compiled over 30 open-wheel championships through the ’80s and ’90s. Now, in the 21st century, Shaver engines prove themselves time and time again. Claiming victories at the most prestigious races across the country, including the Knoxville Nationals, King’s Royal, The World 100, The Gold Cup, The DIRT Cup, and Syracuse. Shaver has become the name top racers could count on for consistency and reliability with unmatched horsepower; he also knows a thing or two about 348s and 409s, and recently built both.

Using later gaskets/heads on an early block will result in a massive coolant leak.

Using later gaskets/heads on an early block will result in a massive coolant leak.

To power the 2011 AMSOIL/STREET RODDER Road Tour ’55, Shaver bored a 409 to 4.350 inches and lengthened the stroke to 4 inches to create a 474-inch torque. Equipped with JE pistons, a SCAT crank and rods, along with a COMP Cams hydraulic roller cam and gear, the big W cranked out 550 hp on the dyno. But thanks to the FAST fuel-injection system the engine started easily every time, idled without loading up, and performed flawlessly.

The smaller of the two engines started life as a 348 and now displaces 440 inches, thanks to a 4.185-inch bore and a 4-inch stroke. It also uses SCAT rods and crank and COMP Cams valvetrain components, including a hydraulic roller cam.

Note the cooling passages that have been welded shut to work on the early block. As the combustion chambers are in the cylinders, the heads for W engines are flat.

Note the cooling passages that have been welded shut to work on the early block. As the combustion chambers are in the cylinders, the heads for W engines are flat.

Regardless of the intended use, race or street, Shaver’s engine building reputation comes from a combination of scrupulous attention to detail and the latest and greatest equipment in an immaculate facility. When Shaver’s team builds an engine, perfection is the goal. Our 409 was line honed to ensure the main bearing bores were perfectly aligned, which eliminates any excess friction. From that true centerline the decks can be made the same height and parallel to the crank, which standardizes the compression ratios in all cylinders.

With the block blueprinted, the crankshaft and all the parts attached to it are balanced for smoothness and longevity. All clearances are checked and when it’s time to put it all together final assembly takes place in surroundings that are clean enough to make any mother proud.

The final touch on our Road Tour engine was a dyno test and tune session. With timing and air/fuel ratios optimized, it was ready to go—and we can tell you it really does just that.