Chevrolet's crate engines have been used in racing now for several years. And while racers far and wide still debate the merits of crate racing (right along with the weather, politics, and the quality of the food at the local track), there's no doubt that crate motors are now a major part of the racing landscape.

One of the main benefits of crate engines--specifically Chevrolet "602" crate which is outfitted with iron cylinder heads and the more powerful "604" crate which has aluminum heads--is that they are quite affordable compared to most purpose-built racing engines. The iron-headed 602 engine (PN 1958602) is the least expensive at just under $4,000. For that you get a cast-iron block with four-bolt mains and a one-piece rear main seal. The crank is nodular cast-iron, the heads are Vortec with 64cc chambers. Powdered metal rods and cast-aluminum pistons provide a 9.1:1 compression. An oil pan with kickouts and large breathers on the left-side valvecover are the major concession to circle track racing. Altogether, the 602 engine is capable of 350 hp and 390 ft-lb of torque and a redline around 6,200 rpm thanks to lightweight springs and hydraulic lifters. It may be pretty pedestrian for a race engine, but it does work when everybody on the track is racing the same thing.

When more power is called for, there's Chevrolet's 604 crate engine (PN 88958604). It upgrades the package to Fast Burn aluminum heads, a forged steel crankshaft for improved strength, a high-rise single-plane aluminum intake, and 9.6:1 compression. It costs about a grand more, but for that you get 400 hp and 400 ft-lb of torque.

Either way, the crate motors are so limited in power, that any small difference between two of the same type can result in a real advantage on the racetrack. Both types of engines are sealed and while certified rebuilders are allowed to refresh the engines, when it comes to major repairs it's often a simpler matter so simply replace the entire engine.

As a result, there are plenty of crate engines available if you know where to look. As a way to recoup some of their costs, many crate racers sell their old engines to hot rodders or mechanics, but more as still gathering dust in the corners of race shops across the country.

We couldn't help but think that these castoffs have the right bones for a great engine build. Sure, the hydraulic roller lifters, cast pistons, and relatively low compression aren't great for racing, but both crate engines have components that can be used to make a quality hand-built race engine. So after a little--OK, a lot, actually--bench racing we decided to take a shot at seeing what could be built from a refuse crate engine. The sweet spot for reusing parts seems to be in the Street Stock classes, so we chose what we figured to be a typical rule book for a high-end Street Stock class. We'd find a used crate engine on the cheap, reuse what we can, and build a Street Stocker. The thinking is that by doing this, a racer can use the savings from his or her crate recycling program to invest in components that can actually help him gain an advantage on the competition. At least that's how the thinking went--we just had to do it to see if we were right.

The first step, obviously, was to find an appropriate donor motor. You might be able to get away with using the 602 engine's cast crank and powdered metal connecting rods if you are building a Pure Stock motor, but our plan had us aiming at the higher level Super Street class. This meant we wanted the forged crank from the 604. After a little searching we found a candidate that had been pulled from a race car and basically abandoned after a blown head gasket made it unfit for racing. We agreed to cough up a grand for the engine, which was probably a bit on the high side compared to what you will be able to get one for with a little haggling, but we considered it a way to help a racer get back on the track.

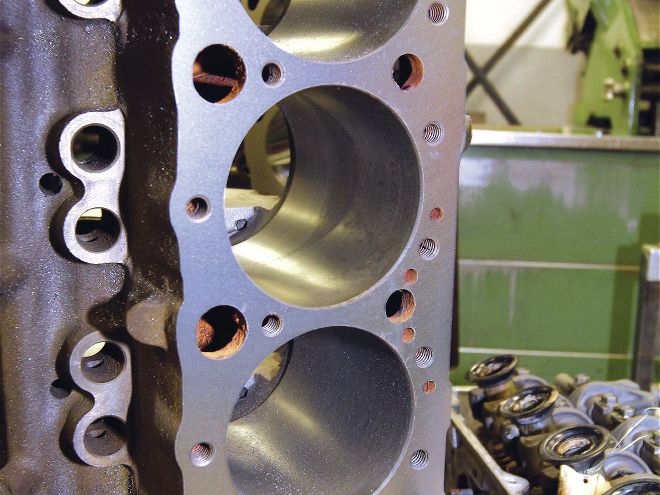

The engine we purchased had already been torn down, so we don't have any photos of it together. But it did show signs of water having sat in a couple of the cylinders. We also noticed that a couple of the rod journals on the crank had been scratched by the rod bolts during disassembly--which is annoying but not a deal killer. Overall, the parts we wanted looked to be in decent shape and the rest will likely be finding its way onto ebay anyway, so we considered the project a go.

The first step was to take the block and crank to be machined. We used KT Engine Development in Concord, North Carolina, which specializes in race engines. In this installment we'll take a look at a few of the components we'll be adding and our reasons why, machine up the block, fit the bearings and assemble the short block. So follow along!

Eventually, we hope to put the completed recycled crate engine into a race car and put it to the test in real competition. We're shooting for a typical Super Street class, which is a high-end Street Stock racing usually on dirt. So we came up with the most common rules for this class. These fit no particular racetrack--so if your track has a Super Street-type class there will probably some differences in what you are allowed--we simply came up with what we have found is typical at most tracks. This means we may have to make a few changes when we do choose a specific track to race, but at least this allows us to make a real game plan.

Block--Cast-iron, may over bore 0.060

Crank--48 pounds minimum weight, can't knife edge, stock stroke for engine size

Pistons--Any flat-top, may float wristpins

Rods--Any steel rod, must be stock length, may be bushed

Heads--Stock or stock replacement, no Vortec, no porting, all bowl work must be in line with valve guide, screw-in studs allowed

Valves--Must be steel, maximum size 2.020 intake 1.600 exhaust

Rocker Arms--No shaft mount, may be steel or aluminum, roller tips allowed

Intake--Edelbrock 5001

Camshaft--May run solid or hydraulic, flat tappet only, 0.500-inch max lift measured at the valve (0.025 lash allowed), lifters must be stock diameter for engine run

Exhaust--Headers allowed, no Tri-Y collectors

Carburetor--May run Chevy Quadrajet, Ford Motorcraft, or box stock Holley 650 (PN 4777), carb spacer maximum 1 inch

Timing Chain--Chain only, no belts

Oil System--Wet-sump only, any pan

After a little searching we found a candidate that had been pulled from a race car and basically abandoned after a blown head gasket made it unfit for racing

The connecting rod is very highly engineered and is fully machined, so even with the reduced mass, it should be capable of holding up to high rpm's and 500-plus horsepower in a racing environment