Technology has had a positive effect on traditional Pontiac performance. Today’s monster mills perform considerably better on the dragstrip than yesterday’s race engines, but are often so reliable and docile that they can be driven on the street regularly. While much of that can be attributed to cylinder-head and intake-manifold design, as well as fuel and ignition-system advancements, modern valvetrain components are equally as responsible.

A roller camshaft is among the most popular modifications that can improve both performance and driveability. Modern hydraulic rollers are much more reliable than ever before, and because they’re not susceptible to lobe and/or lifter failure related to modern-spec oil, they are growing increasingly popular. Many shy away, however, when they learn of the relatively high cost when compared to a $200 flat-tappet camshaft kit.

While many hobbyists understand the benefits that hydraulic-roller camshafts can offer, rarely has it ever been quantified in a back-to-back testing scenario, so that’s what we did. We ordered a custom-spec hydraulic roller from Comp Cams and compared its performance to two high-performance flat-tappets that we tested previously. Follow along as we share the results!

Our ’76 Trans Am is a dedicated street car that’s often driven in stop-and-go traffic and for relatively long distances. If you’ve read “Affordable Attitude Adjustment” (HPP, June ’11), you know our quest was to achieve maximum performance while maintaining maximum driveability from our relatively mild combination, which is assembled mostly of original Pontiac components. In that article, we went to C&S Dyno Shop in Omaha, Nebraska, to compare two high-performance hydraulic flat-tappet cams from Nunzi’s Automotive.

On the Mustang-brand chassis dyno, our moderately-built 467ci generated 355 hp and 402 lb-ft of torque at the rear tires with the 2043NHL cam (244/252 degrees at 0.050-inch). We then installed the slightly smaller 2042NHL (232/243 degrees at 0.050-inch) and as expected, its wider lobe-separation angle and lesser duration significantly improved driveability, while maintaining an equal amount of rear wheel torque (403 lb-ft) but reducing peak horsepower to 346 at the tires.

Though the driveability improvement was the exact result we sought, it didn’t take us long to begin exploring ways to restore the peak horsepower we lost, but we weren’t willing to compromise the newfound street manners. A number of professional Pontiac builders recommended a hydraulic roller.

A roller camshaft has a distinct advantage over a flat-tappet. The lifter body is fitted with a roller wheel that reduces friction, which not only improves efficiency and can provide a slight fuel economy increase, but it also allows for a lobe design that opens and closes the valves at a quicker rate. That keeps the valves open longer at mid-to-high lift, improving cylinder fill and performance. The quicker lift rate also allows the roller wheel to stay on base-lobe longer, improving efficiency and reducing emissions.

To explain how this occurs, consider two similar camshafts. One is a hydraulic flat-tappet and the other a hydraulic roller, and both share identical 0.050-inch duration specifications. A hydraulic roller will contain less seat-to-seat (or advertised) duration, and that reduces valve overlap, improving idle quality and increasing vacuum. A hydraulic roller will also contain more duration at 0.200-inch on up, and that can extend and improve high-rpm performance.

Adding hydraulic action to a roller cam provides consistent performance and quiet operation. These positive attributes are what make roller cams ideal for modern auto manufacturers. When hydraulic rollers were first developed years ago, reliability was inconsistent, but modern production techniques have made them extremely durable, offering thousands of miles of issue-free performance.

Many companies, such as Comp Cams, Crane Cams, and Crower Cams, offer a wide array of Pontiac roller camshafts, hydraulic roller lifters, and all other components required to operate reliably to at least 6,000 rpm, and possibly more.

We wanted to maintain low-speed street manners that were as good as part number 2042NHL, and hopefully as much top-end performance as with the larger 2043NHL. Since we’d already measured the performance of both flat-tappet cams and no other parts would be changed, a follow-up chassis-dyno session would give us the chance to accurately determine how much can be gained from a hydraulic roller.

Because low-speed street manners are so important to us, we wanted a cam with a wider lobe-separation angle (LSA) to produce better idle quality and greater average power. We also knew that long-stroke, street-driven Pontiacs tend to perform best with 10 to 12 degrees of additional exhaust duration because of the slight exhaust flow deficiency associated with original Pontiac cylinder heads. That meant finding a hydraulic roller with 0.050-inch intake duration in the mid 230s, exhaust duration in the mid-240s, and an LSA of 112-114 degrees.

Since we couldn’t find a cam with the exact specs we needed for our controlled comparison, we decided to order a custom unit, and Comp Cams has the largest array of lobe choices. We conferred with Nunzi, who recently retired but was willing to help us decide what would work best for the No. 197 heads he prepared for us many years ago.

We created a hydraulic roller with 236/248 degrees of 0.050-inch duration, 0.520/0.560-inch valve lift, an LSA of 113 degrees, and an intake centerline of 110 degrees. We must point out that when selecting a particular lobe for a custom cam, duration and lift are not separate choices. A limited number of duration/lift combinations are available. The chosen 236/248 lobes had greater valve lift with 1.5:1-ratio rocker arms than either previously tested flat-tappet. However, our No. 197 heads only increase 5 cfm from 0.500- to 0.550-inch lift and nothing beyond that, so the performance effects from increased valve lift are negligible.

Higher-rate valvesprings are required to accommodate the higher opening and closing rates of a hydraulic roller. When Nunzi rebuilt our cylinder heads, he used valvesprings best suited for a flat-tappet. At 1.75-inch installed height, seat pressure was 110 lb-in and open pressure at 0.500-inch lift was 300 lb-in. With our 1.75-inch installed height, Comp Cams recommended its No. 987 valvespring set, which offers about 130 lb-in of seat pressure and 330-340 at maximum valve lift. We are reusing the high-quality valvespring retainers and locks that Nunzi originally supplied, but Comp Cams can provide you with new components if the quality of your originals is unknown.

We placed our order with Comp Cams and our custom hydraulic-roller camshaft, hydraulic roller lifters, and valvesprings were on our doorstep in less than a week. Since custom-length pushrods would be required, we also ordered an adjustable pushrod-length checker from Comp, reasoning we could then measure for the appropriate length during assembly and have them to us by the time we were ready to finish up.

Installation isn’t any different than with a typical flat-tappet camshaft. Since we have covered that before in HPP, we will only discuss the highlights here. Our 467 was partially disassembled, and the existing flat-tappet cam and lifter set were removed. Each lifter was closely inspected for abnormal wear as it was removed and set aside.

The valvesprings were swapped, while the cylinder heads remained on the engine using specialized equipment from K-D Tools. Removing the spark plugs and addressing each cylinder independently, the piston was brought to top dead center (TDC), an air-holding hose (PN 2992) was threaded into the spark plug hole, and an air hose was connected to pressurize the cylinder. Every engine opening was covered to prevent a valve lock from falling into the engine during removal, while a valve-spring compressor (PN 912) was used for its intended task. (You may need a forceful blow from a soft hammer on the retainer to jar the locks loose if they’ve been installed for a while.)

Working from the rear forward on each cylinder bank, the existing valve-springs were carefully removed and the new units were installed. Just before installing the last pair, we inserted a lightweight test spring as we prepared to measure for required pushrod length. The valve-stem tip received a light smear of white grease; a pair of roller lifters, the pushrod-length checker, and one rocker arm was installed. The pushrod was adjusted and the engine was rotated until the rocker’s roller tip was in the center of the valve stem throughout its entire travel. Our particular engine required a length of 8.95 inches, and Comp Cams had a set of its Hi-Tech pushrods on our doorstep in a couple of days.

The camshaft was degree’d and determined to be ground to the exact specifications we requested. The engine was sealed up using several new Fel-Pro gaskets; once the pushrods arrived, the hydraulic roller lifters (PN 857-16), pushrods, and rocker arms were installed. The rocker arms were then adjusted to half-turn of lifter preload, and the No. 1 piston was brought to TDC on the compression stroke to prepare for initial startup.

Some roller lifters can interfere with the standard Pontiac valley pan, particularly the deeper units from the mid-to-late ’70s, and we found this to be true in our case. While relieving the pan’s contact areas with a hammer works suitably, the Tomahawk Valley Pan from Pacific Performance Racing fits and functions like a shallow-center original, but is specifically designed for use with roller lifters.

Before firing, the coolant system was refilled and the engine was treated to fresh oil and a new filter. Just before dropping in the distributor, we primed the oil pump to ensure the hydraulic lifters would immediately receive oil.

The roller’s hardened-steel cam gear and the distributor’s original cast-iron gear are incompatible, so a high-quality composite unit from BOP Engineering was installed. We then primed the carburetor, hit the ignition, and the 455 immediately roared to life.

There is no particular break-in procedure required with a roller camshaft, so we elevated the idle speed a few hundred rpm so the engine would warm up quicker while we inspected for oil or coolant leaks, and topped off the coolant system. Once the engine neared its normal operating temperature at idle, we recognized that the exhaust note was deeper and louder, and emitting a more forceful pop—all of which indicates a higher running cylinder pressure. The note was very aggressive, like the larger flat-tappet we ran previously.

We prepared for our initial testdrive by resetting base timing to 12 degrees, readjusting idle speed to 800 rpm, and trimming the Quadrajet’s idle mixture screws for highest vacuum, which was about 3 inches more than before, now at a total of 12. Once on the road, the new hydraulic roller camshaft seemed to improve throttle response and provide smoother acceleration at part-throttle despite its radical sound. Under a full-throttle pull, the engine felt just as powerful as before, but the only way to quantify that feeling was with another trip to the chassis dyno.

Installing a hydraulic roller into an existing Pontiac V-8 can be a pricey endeavor since it requires many associated components. Any cam swap, whether to a new flat-tappet or roller, will require new gaskets, coolant, and oil, which can be considered fixed costs. The cam and lifters, pushrods, valve-springs, and a composite distributor gear required for our particular swap totaled just under $1,200. The cost when upgrading to a hydraulic roller during a rebuild is much more manageable since new valvesprings and hardware, rocker arms, and pushrods will be purchased anyway.

The results of our dyno testing prove two distinct points about hydraulic camshafts in general. Excellent performance is quite possible from a quality flat-tappet, and they remain an excellent choice if you’re building an engine on a budget. If you feel that maximum driveability without sacrificing performance is important and your budget allows it, a quality hydraulic roller may provide at least as much performance with less duration than a radical flat-tappet, while providing more torque than a smaller flat-tappet. And we have the dyno sheets to prove it!

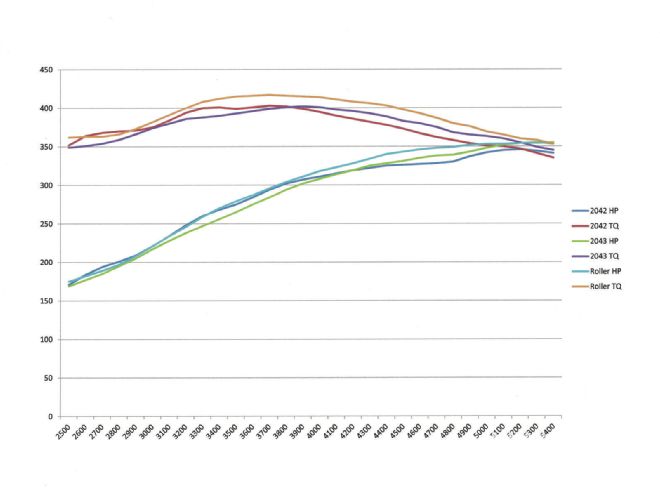

The dyno graph tells the tale of more average torque and horsepower through the entire pull for the roller cam.

The dyno graph tells the tale of more average torque and horsepower through the entire pull for the roller cam.

We contacted Tom VanVugt at C&S Dyno Shop to schedule another appointment. As soon as the Firebird was strapped to the rollers and the first pull began, everyone familiar with the past pulls could tell that the 467 revved quicker from the start point of 2,500 rpm. Once the pull commenced, the computer screen revealed 355 rwhp at 5,300 rpm and 417 rwtq at 3,700. Subsequent pulls included various timing and carburetor settings, but we couldn’t improve upon our first pull.

When compared to our flat-tappet camshaft dyno tests, the hydraulic roller delivered just as much peak horsepower as the larger flat-tappet, and improved peak rear-wheel torque from either cam by 15 lb-ft. Comparing average numbers from 2,500 to the horsepower peak was more impressive. The hydraulic roller clearly made more power at every point, increasing average rwhp and rwtq values by 10 and 14, respectively. And it accomplished this without sacrificing, but actually improving street manners.

Cam Jet Pri. Rod Sec. Rod Timing Rwhp Rpm Rwtq Rpm Avg Hp 2,500 to Hp Peak Avg Tq 2,500 to Hp Peak Avg A/F Ratio 2042NHL 73 42 BF 36 346 5,200 403 3,800 282 375 13.0 2043NHL 73 42 AX 36 355 5,400 402 3,800 284 375 12.7 Custom 73 42 BF 36 355 5,300 417 3,700 294 389 12.9