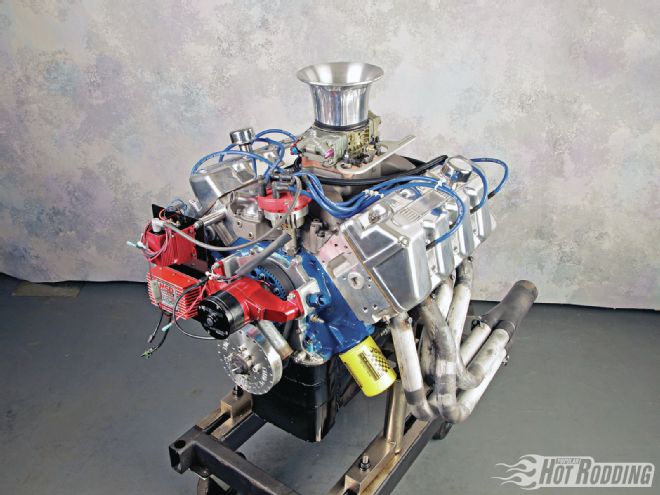

If there was an equivalent of a Victoria’s Secret catalog for engine parts, the Boss 429 engine would seize its rightful place on the cover. Blown flatheads needn’t apply. With its gloriously wide cylinder heads and beautifully scalloped valve covers, its visceral appeal and visual presence lingers somewhere between exotic and erotic. The only way a Boss motor could look any cooler is if it were topped with a fistful of Webers breathing through individual polished aluminum throttle stacks. Thanks to its hot shape, scarcity, and storied history in NASCAR competition, the mystique surrounding the Boss 429 in Ford circles makes grown men do funny things. Todd Miller of TM Enterprises is one of those guys, and his love of the fabled Boss platform inspired him to start up an aftermarket operation dedicated to keeping the Shotgun motor alive and kicking. To show what a modern iteration of a Boss is capable of, he built one to run up against some of the most extreme street motors in the country at the 2010 AMSOIL Engine Masters Challenge.

Boss or Bust

In the Blue Oval camp, the love of the Boss 429 runs deep largely because so few of them were ever built. After NASCAR banned the FE-based 427 Cammer motor in 1965, an elite cadre of defiant Ford engineers went back to the drawing board and whipped up the Boss 429. Like the Chrysler Hemi it was designed to chase down on the high-banked superspeedways, the Boss featured a somewhat standard short-block topped by hemispherical cylinder heads packing massive 2.400-inch intake valves (2.280-inch for street variants). Essentially a fortified 385-series big-block bottom end with a wicked set of heads, the Boss 429 started out like gangbusters, with Fords powering the 1969 Daytona 500 winner along with six of the Top 10 finishers in that race. Unfortunately, Ford determined that the Boss 429 program was too expensive after just two seasons of competition, and killed it off after the 1970 season.

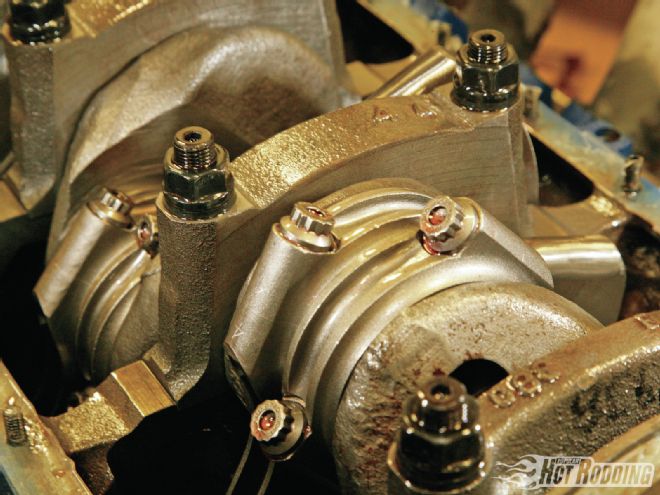

The guts of TM Enterprises’ 477ci big-block is as ordinary as it gets. The production D9TE block, plucked for $35 out of a salvage yard, is the same unit that came equipped in hundreds of thousands of Ford pickups through the decades. The crank is a stock truck casting as well.

The guts of TM Enterprises’ 477ci big-block is as ordinary as it gets. The production D9TE block, plucked for $35 out of a salvage yard, is the same unit that came equipped in hundreds of thousands of Ford pickups through the decades. The crank is a stock truck casting as well.

Per NASCAR homologation rules at the time, Ford had to build a minimum of 500 Boss motors in street cars, most of which landed in Mustangs. Since the Boss 429 only competed in the Grand National Series for two seasons, the number of street variants still in existence is extremely small to say the least. That’s where companies like TME step in. Hot rodders discovered long ago that the Boss Hemi heads will bolt right up to a standard 429/460 block without much modification. Miller says that other than the addition of four-bolt main caps, priority main oiling system, beefier rods, and forged crank, the Boss 429 short-block isn’t all that different from a standard 385-series big-block.

As with the rest of the short-block, the oiling system is an exercise in frugality. It features a Melling stock replacement pump and a factory Ford truck pan modified for additional volume. Other mods include provisions for external oil passages drilled into the block to accommodate the drain backs on the Boss heads.

As with the rest of the short-block, the oiling system is an exercise in frugality. It features a Melling stock replacement pump and a factory Ford truck pan modified for additional volume. Other mods include provisions for external oil passages drilled into the block to accommodate the drain backs on the Boss heads.

For Ford enthusiasts interested in a Hemi-headed conversion, the problem has always been tracking down the heads, so several years ago Miller decided to make his own. Although his day job as a foundry equipment builder keeps him plenty busy, Miller found the time to design a set of all-new Boss 429 Hemi head castings. The AMSOIL Engine Masters Challenge served as a perfect opportunity for Miller to showcase his heads and exercise his passion for the Boss platform. The only thing I was interested in building for the EMC was a Boss motor, he says. It’s probably not the most practical choice for this kind of competition, but for me it was between building a Boss or building nothing at all. All Boss fans like the exotica that comes with these motors, and I’m no exception.

Atypical Formula

In an effort to swing the pendulum back in the direction of street performance, the rules for the 2010 EMC sought to ban hardware rarely seen on the typical street machine. The 2009 competition had seen an influx of tunnel-rams and dual-quad carbs, so in 2010, carbureted motors were limited to a dual-plane intake and a single four-barrel carb. Although EFI motors were allowed to use any commercially available fuel-injected manifoldas long as it had a single throttle-body and cast-in injector bungsall engines had to run hydraulic roller cams limited to a maximum of .650-inch valve lift. Given these restrictions, TME’s Boss combines an interesting mix of components that set it apart from the typical EMC motor. At 477 ci, it’s a giant in relation to the rest of the contestants. In fact, of the 38 entrants, only four fielded motors with more cubic inches than TME’s 477. Since the EMC scoring system averages horsepower and torque from 2,500 to 6,500 rpm, then divides those totals by an engine’s displacement, having more cubic inches doesn’t always pay off. As such, more than half of the EMC field (24) was comprised of small-blocks, something that can’t be chalked up to mere coincidence. Miller agrees: Since you have to run through a 3.5-inch exhaust system and are limited in valve lift, the rules naturally favor a smaller motor. All of the top finishers had motors that were right around 400 ci.

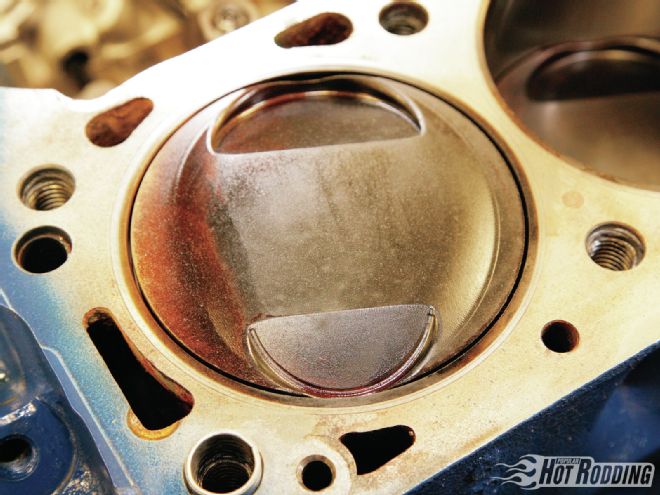

Due to their unique valve positioning, Ford Hemi heads require different pistons than a standard 429/460 big-block. As hard as it may be to believe, however, the Diamond pistons aren’t custom one-offs. TME has worked closely with Diamond over the years, and the company now offers off-the-shelf pistons that perfectly match up with the chambers on the TME heads. All Boss heads retain the same bolt pattern as a standard 385 series big-block.

Due to their unique valve positioning, Ford Hemi heads require different pistons than a standard 429/460 big-block. As hard as it may be to believe, however, the Diamond pistons aren’t custom one-offs. TME has worked closely with Diamond over the years, and the company now offers off-the-shelf pistons that perfectly match up with the chambers on the TME heads. All Boss heads retain the same bolt pattern as a standard 385 series big-block.

Despite the dominance of smaller-displacement combinations, Miller’s reasoning for going big makes perfect sense. I don’t build engines full time, and for me it’s just a hobby gone wrong. I don’t have the resources to build a dyno prima donna motor, so I had to build an affordable combo that I could actually put in a car and have fun with on the street, he says. To keep costs down, Miller scored a plain-Jane production 460 block out of a salvage yard for $35. The displacement we ended up with was half by accident and half by economy. The Boss was originally designed as a high-rpm motor, so we knew we had to downsize it significantly to tailor the powerband for the EMC points system. While big-block Fords are easy to make big, they’re very hard to make small due to their large 4.360-inch bore. It was questionable as to whether or not the block was going to clean up at .030 inch, so the machine shop just bored it .080 over. The 4.440-inch bore was then matched up with a 3.850-inch crank out of a stock Ford truck motor, as we felt that was a better option than a shorter 3.590-inch stroke crank out of a 429. I’d love to build an under-square motor with a 4.250-inch bore and a 4.500-inch stroke to try to boost torque, but that would require sleeving the block, and I wasn’t interested in spending that kind of money.

With enormous 9⁄16-inch ARP main studs, the factory two-bolt caps can easily handle 800-plus horsepower. As was common for the day, the 429/460 boasts large 3.000-inch main journals. This makes for a stronger crank at the expense of increased friction, but most 460s were never intended for high-rpm use.

With enormous 9⁄16-inch ARP main studs, the factory two-bolt caps can easily handle 800-plus horsepower. As was common for the day, the 429/460 boasts large 3.000-inch main journals. This makes for a stronger crank at the expense of increased friction, but most 460s were never intended for high-rpm use.

Due to the limited selection of aftermarket big-block Ford connecting rods, Miller ground the truck crank’s rod journals down from 2.500 to 2.200 inches. This change allowed tapping into the massive catalog of big-block Chevy rod offerings, and Miller opted for a set of 6.535-inch H-beams from Scat. Although the 460 block’s generous 10.322-inch deck height has plenty of real estate for much longer rods, Miller felt that the increase in rod angularity of a short-rod combo would yield dividends in the low-end torque department. Rounding out the rotating assembly is a set of Diamond 11.4:1 pistons whose crowns perfectly follow the contours of the Hemi combustion chambers. When it came time to select a camshaft, Miller relied upon the expertise of COMP Cams. Given the lift limitations that were put into place in 2010, I thought the smart thing to do was to call up Billy Godbold at COMP and have him spec out a cam for us. He designed a 247/251-at-.050 hydraulic roller grind for us with .634 lift, and it ran best at 2 degrees advanced just like he said it would, Miller says.

Swinging on the Scat 6.535-inch big-block Chevy rods are Diamond 11.4:1 pistons. They have been treated with a ceramic coating on the crowns, and a dry film lubricant on the skirts. Total Seal rings keep combustion gasses in the chamber, and the rotating assembly rides on King Pro Series bearings.

Swinging on the Scat 6.535-inch big-block Chevy rods are Diamond 11.4:1 pistons. They have been treated with a ceramic coating on the crowns, and a dry film lubricant on the skirts. Total Seal rings keep combustion gasses in the chamber, and the rotating assembly rides on King Pro Series bearings.

Lung Surgery

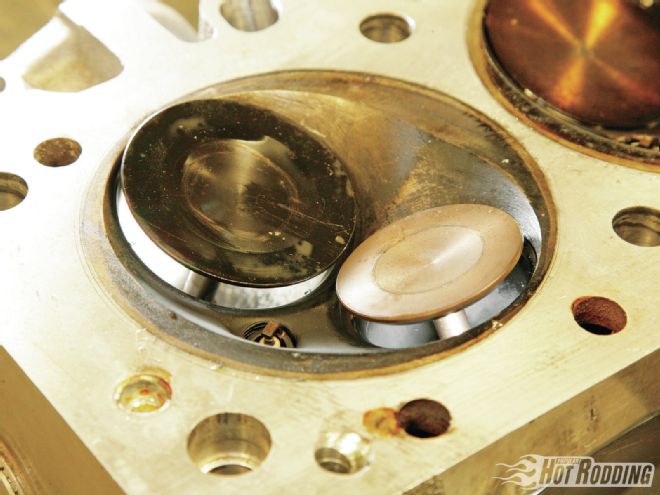

Granted most hot rodders are smart enough to realize that big ports don’t always work best, but the sheer cross-sectional area of a Boss 429 cylinder head is truly an awe-inspiring sight. You can literally stuff a tennis ball down the intake ports. TME offers two variants of its Boss heads, including CNC’d stock replacement castings as well as more aggressive 430 heads that flow 430 cfm out of the box. For the 477, Miller massaged the 430 castings up to 460 cfm at .700-inch lift, but they were clearly too large for the 2,500 to 6,500 rpm operating range dictated by EMC rules. As a fix, Miller added material to the port floors in an effort to reduce cross-sectional area and boost air velocity. The floor of these ports is so lazy that I don’t think adding material there hurt airflow at all. These weren’t ringer heads, and accurately represent what one of our customers can buy, Miller says. We cleaned up the ports a little bit, but otherwise the heads are untouched. At 477 ci, we didn’t feel that it was worth it to spend a lot of time porting the heads. Ultimately, I still think the ports were too lazy, and in the future, I’d like to pinch down the size of the ports even more to see if that increases air velocity. For our customers, we offer our heads with both round and D-shaped ports.

The Hemi chambers boast dual quench pads, which promote combustion efficiency and a quicker burn rate. The proof is in the pudding, as the TME heads required just 28 degrees of total ignition advance. A key benefit of a Hemi head is that it positions the intake and exhaust valves at opposite sides of chamber, freeing up space for massive 2.450/1.900-inch valves. This also means that the valves move closer to the bore centerline as they open, instead of shrouding up against the cylinder wall as in a Wedge head.

The Hemi chambers boast dual quench pads, which promote combustion efficiency and a quicker burn rate. The proof is in the pudding, as the TME heads required just 28 degrees of total ignition advance. A key benefit of a Hemi head is that it positions the intake and exhaust valves at opposite sides of chamber, freeing up space for massive 2.450/1.900-inch valves. This also means that the valves move closer to the bore centerline as they open, instead of shrouding up against the cylinder wall as in a Wedge head.

The balance of the induction system was yet another instance where budget took precedence over ultimate performance. Considering that five of the top six qualifiers fielded EFI engines, the dual-plane intake manifolds mandated on all carbureted motors obviously choked them up big time. We wanted to run a single-plane intake with EFI, but ran out of time to finish it up, Miller says. The intake we ended up using is the same 42-year-old dual-plane unit that came equipped on Boss 429 Mustangs, which is the only dual-plane unit that’s out there for these motors. It was impossible to reach certain areas of the runners for porting, and there was as much as a 50-cfm variation in flow from one runner to the next. Needless to say, we affectionately called it the aluminum cork.

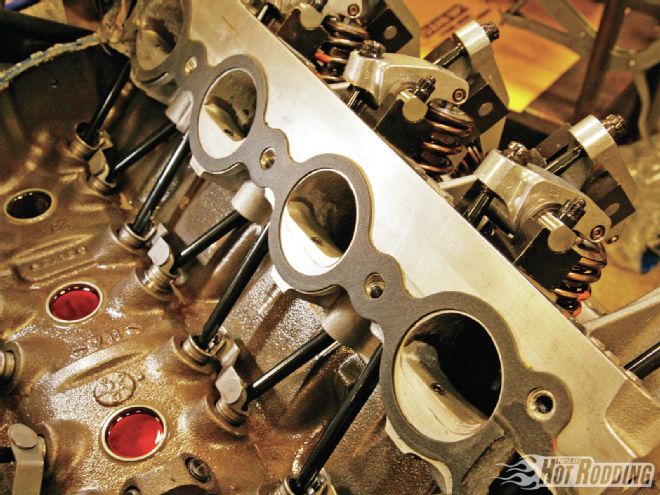

Even without the rockers in place, the TME Hemi head looks incredibly manly. Compared to a factory Boss casting, the TME head has a thicker deck, beefier head bolt bosses, and are cast from 356-T6 aluminum. The TME head also ditches the cumbersome factory O-rings on the deck surface and makes do with a regular head gasket.

Even without the rockers in place, the TME Hemi head looks incredibly manly. Compared to a factory Boss casting, the TME head has a thicker deck, beefier head bolt bosses, and are cast from 356-T6 aluminum. The TME head also ditches the cumbersome factory O-rings on the deck surface and makes do with a regular head gasket.

Game Day

When the time arrived to put the TME 477 to the test, it ripped out 654 hp at 6,000 rpm, and 605 lb-ft of torque at 4,600 rpm. Taking its displacement into account under the EMC scoring system, this was good for a 17th Place finish out of a field of 38. Considering the unusually high attrition rate at the 2010 EMC, in which nine engines failed to make it out of qualifying without mechanical failure, a mid-pack finish from a privateer entrant on a modest budget is more than respectable. Regardless of where it finished, perhaps the most significant aspect of TME’s 477 is that it’s one of the best examples of the back-to-the-basics theme the 2010 EMC sought to recapture. This engine isn’t really all that scienced-out, and there’s a lot left in it. It uses mostly off-the-shelf parts, and anyone can build a motor just like it, Miller says. There’s a total of about $18,000 in it, which is a fraction of what the some of the big-name competitors spend on their engines. The good thing is, I don’t have to worry about what I’m going to do with it now that the competition is over. I can put it in just about any car and go cruising.

The unique valve placement of the Hemi heads means that the exhaust pushrods are nearly an inch longer than the intake pushrods. The extreme angles and positioning of the pushrods also necessitate the use of Crane Z-bar-style lifters for additional clearance.

The unique valve placement of the Hemi heads means that the exhaust pushrods are nearly an inch longer than the intake pushrods. The extreme angles and positioning of the pushrods also necessitate the use of Crane Z-bar-style lifters for additional clearance.

On the Dyno

TME 477ci Big-Block Ford

RPM TQ HP 2,500 450 214 2,600 473 237 2,700 496 255 2,800 510 272 2,900 520 287 3,000 533 304 3,100 543 321 3,200 548 334 3,300 546 343 3,400 538 348 3,500 533 355 3,600 531 364 3,800 547 396 3,900 563 418 4,000 577 440 4,100 489 460 4,200 597 477 4,300 600 491 4,400 601 504 4,500 604 518 4,600 605 530 4,700 603 540 4,800 604 552 4,900 604 563 5,000 601 572 5,100 598 581 5,200 597 591 5,300 598 603 5,400 602 619 5,500 601 629 5,600 595 634 5,700 589 640 5,800 582 643 5,900 577 648 6,000 572 654 6,100 562 653 6,200 548 647 6,300 535 641 6,400 526 641 6,500 516 639