Tips And Tricks

Build Your First

We recently spent a couple of days at JMS Racing Engines talking with owner Mike Johnson and his machinists and builders to get the scoop on what makes a successful budget performance engine build. We're assuming you're starting with an engine that is in good condition and hasn't had more than one overbore, you're planning to reuse as many of the stock components as you can-upgrading to higher performance pieces as your budget permits-and you're doing the disassembly and reassembly yourself. As with any complicated process like this, there are plenty of myths to bust and just as many procedures to follow. We'll break down everything into bite-sized pieces.

Devise A Plan

The most important part of any engine build is a good plan. And by good we mean one that is realistic and fits within your budget. Decide how much you can afford to spend and what you have to work with. Are you starting with a lightly used original-bore stock block that just needs new rings, bearings, and a hone or are you starting with a mystery motor of unknown origin? For an example of how quickly costs can escalate when building a found engine, see Jeff Smith's boat motor build in the Feb. '08 issue ("A Boat Anchor Into a 611HP Screamer.").

Keep in mind that the cost of the engine is only part of the total build. There are myriad other factors to consider: Will your cooling system be able to keep your more powerful engine from overheating? Do you need to reinforce the frame or add a rollbar? Will your transmission, rearend, and axles live behind it? Will you need bigger wheels and tires for better traction? Do you have all the tools you need and space to do the work?

At some point, you'll eventually come to the age-old question: Am I building a street car or a race car? Decide on this quickly and the rest of the build will start to fall into place. We'll guess that most of our readers will have a formula that goes something like this: I have a 3,200-pound car with a C4 and 3.55:1 Traction-Lok rear, and I have a stock 5.0 that came out of a '90 Mustang. I want an engine that will let me drive to the dragstrip and run low 13s or maybe compete in a few local autocross events. I want it to be able to do burnouts at will, I want to be able to drive it to cruises and car shows without overheating or having mechanical problems, and I want it to sound good. I have $3,000 to spend on building the long-block.

Choose A Shop

The next step is to approach a few of your local machine shops to discuss your plan and see what they recommend. Can they work within your budget, and what would you get in the engine they'd build?

JMS' Mike Johnson says it's important to find a machine shop you can trust. Look at the shop. Are things clean and orderly, especially in the assembly area? How long has it been in business? What do its customers have to say about the shop? Are the builders willing to spend time with you discussing your options and answering your questions? If you're met with rudeness or impatience, don't waste your time with that particular shop. Go find another one. By the same token, don't be a pain in the ass. Tell them what you have and what you want and listen to their recommendations. It's OK to discuss why they recommend a certain procedure or brand of parts, but it's probably not a good idea to tell them how to do their jobs.

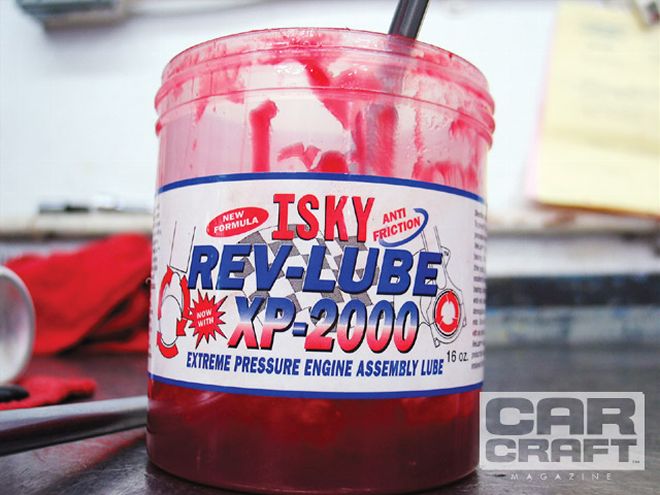

Use a good assembly lube when putting your engine together.

Use a good assembly lube when putting your engine together.

Johnson says Internet know-it-alls and overanxious zealots who focus on the most minute details are often more difficult to deal with than customers who care too little. Any engine builder worth his salt knows which parts and processes work and which do not. Asking for clearances to be machined to the hundred-thousandths of an inch or informing them that Brand X's zinc/krypton bearings are a nonnegotiable requirement for the build because you read about them on some message board won't help you in the long run. Trusting the shop to put together an engine package for you will often result in an engine that makes more power and lasts longer than one in which you micromanage the build. Unless you're an expert machinist and mechanical engineer and know all the nuances of machining and matching parts, let the builder do his job.

Early in the conversation with your builder, the following question will be put to you: Do you want to build a stroker? Johnson says that is often a difficult question for guys on a tight budget to answer. Do you add extra cubes to make more torque, or do you spend your money on the cylinder head to improve airflow and make more horsepower at higher rpm? The answer largely depends on your car: How heavy is it? What is the rear axle ratio? Do you have an overdrive transmission? What are your gear ratios? Discuss all these variables with your builder. His experience will enable him to recommend a package that will best meet your needs.

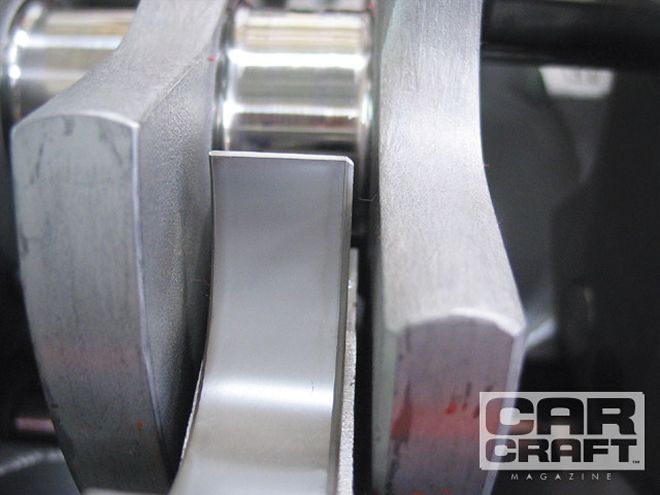

Here's a standard journal crank. Below is a crank with filleted journals.

Here's a standard journal crank. Below is a crank with filleted journals.

Block

Though we'd all love to begin our build with an aftermarket block, the reality is most budgets don't permit it. And honestly, most of us aren't making power levels high enough to warrant the purchase of an aftermarket block. Johnson says the rule of thumb of 1.5 hp per cubic inch is about the limit of most factory engine blocks. So if you have a stock 350 Chevy and are planning to make more than 525 hp, you should be seriously considering a phone call to Dart, World Products, GM Performance Parts, Ford Racing, or Mopar Performance. Why? "Aftermarket blocks have improved oiling, thicker decks, thicker cylinders, and are made with more alloy. They are a stronger block," Johnson says.

Likewise, if the amount of machining you're considering is going to cost more than $1,500, you should also consider an aftermarket block. At that price, the cost of machining is approaching the cost of a new block in some cases, and you'll have a much better engine in the end if you spend a little extra for the aftermarket block. But be careful-aftermarket blocks may require machining of their own and that adds to the total cost.

This is a performance crank with filleted journals.

This is a performance crank with filleted journals.

Still, for most street cars, the stock block will handle a lot of abuse. But there are several things you can do to improve its strength and performance. One of the most popular upgrades is to drill and tap the block to accept four-bolt main bearing caps. Often mistaken as inherently stronger than two-bolt mains, the real purpose of four-bolt caps is to prevent cap dancing or cap walk that occurs on the down load-the load placed on the cap as its adjacent crank throws are rotating down. Of the two types of four-bolt caps, splayed caps are better at controlling cap movement than straight caps. "They spread the clamping load over a larger area and are threaded into a stronger part of the block-the webbing," Johnson explains.

Steel caps resist flex better than stock cast-iron caps but may be a luxury item that could be eliminated for the sake of keeping the build within your budget. If you reuse your stock caps, be sure to keep them in order-this is extremely important. Number them and make some kind of mark indicating which side faces forward. No two blocks are the same; there can be differences in the size, shape, and thickness of components in a single casting. Because the main bearing caps are part of the engine block casting, the caps will vary slightly in shape from one to another, so they need to stay with the journal to which they were originally machined.

A filleted crank needs chamfered bearings.

A filleted crank needs chamfered bearings.

Street and race engines receive basically the same machining processes, but race engines are often cut to a zero deck height meaning the top of each deck is milled flat in relation to the top of the piston at top dead center (TDC). Minimal gap between the top of the engine block and the top of the pistons ensures maximum compression. Also, race engines are finish-honed with finer stones, leaving a smoother finish on the cylinder walls than a typical street hone. This means less friction against the piston rings but more oil consumption-usually not good for a street engine.

Johnson says an often overlooked path to more horsepower is to install a deep-sump oil pan that includes some kind of windage tray. Keeping the spinning crank from dipping into the oil allows the crank to rotate more freely, reduces turbulence in the crankcase, and prevents aeration and foaming in the oil, which can starve the oil pump and cause a drop in oil pressure.

Finally, one of Johnson's requirements is an accurate timing pointer. "You can't be sure the stock one is in the right place or if the mark on the balancer is correct. The best thing is to make your own while the cylinder heads are off. That way, you know exactly where TDC for cylinder No. 1 is." Simple enough. This takes all the guesswork out of setting the timing accurately.

Also, while assembling the engine, be sure to use a good assembly lube. The guys at JMS use Isky Rev-Lube on the cam and lifters and Godson First Lube FL-128 on everything else. "It protects during start-up, and it clings well and doesn't coagulate while the engine is in storage," Johnson says.

Crank

We all know a forged crank is stronger than a cast crank and a billet crank is the top-self, bench builder part, but most street engines can get by with a stock crank, which is typically cast out of steel or nodular iron. A good place to spend your money is on a crankshaft with filleted journals. A fillet is a slight radius rolled between the journal and the webbing of the crank throws. A sharp, 90-degree edge is a prime target for stress risers to form, which can eventually lead to failure at that location. A filleted crank needs special bearings. These chamfered bearings have a beveled cut made along their outside edges to fit the fillets on the crank, so be sure to match the correct bearings to your crankshaft.

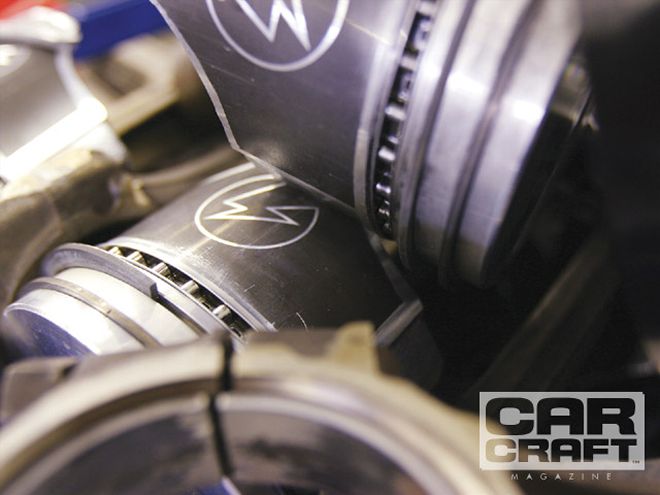

Stock rods versus aftermarket.

Stock rods versus aftermarket.

JMS likes to make its rotating assemblies internally balanced whenever possible. "It's better to keep balance weight off the ends of the crank," Johnson says. "Plus, the customer can use any neutral balance flywheel and damper."

Finally, Johnson tells us he likes to machine the main and rod clearances in a street engine to 0.002 inch versus a race engine that gets a slightly looser 0.003-inch clearance.

Rods

In most cases, you can reuse your stock rods. Johnson tells us aftermarket rods are a relatively new speed part. "Back in the '70s, all we had to work with were either stock rods, or we could buy aluminum or Carrillo rods-and those were considered race only. We made lots of power with stock rods." If you are using a power-adder or plan to rev the engine more than 6,500 rpm, however, you should consider forged rods.

When you are selecting a rod for a power-adder or rpm engine, piston speed is the issue. Take an engine with a 3.75-inch stroke. For one complete revolution of the crankshaft, the piston is traveling 7.5 inches from the top to the bottom of the bore and back to the top again. At 6,000 rpm, the piston is traveling 45,000 inches or 3,750 feet per minute.

Low-tension rings can free up some horsepower but are not recommended for street applications because they don't control oil as well as standard rings. Also be aware that performance rings need to be fitted to match the diameter of the cylinder bores. File-fitting the rings is time-consuming work that can add to the cost of the build.

Low-tension rings can free up some horsepower but are not recommended for street applications because they don't control oil as well as standard rings. Also be aware that performance rings need to be fitted to match the diameter of the cylinder bores. File-fitting the rings is time-consuming work that can add to the cost of the build.

When the piston is at BDC and moving up, the rod is being compressed, and when the piston is at TDC and moving down, it is experiencing tension. The most violent force for the rod to endure is from the tension created at TDC during overlap where the piston is not cushioned by compressed air. A piston assembly (piston, rings, pin, and pin clip) that weighs 600 grams, for example, will weigh 11,250 pounds at 6,000 rpm during overlap. The rod must hold on to the piston as it reverses direction without distortion, which can cause breakage or bearing failure. Heavier pistons make it worse.

Using Scat as an example, its Street I-beam rod will withstand a 6,000-rpm pounding with a piston assembly in the 600-gram range. Its Pro Comp I-beam will survive a 600-gram piston at 7,500 rpm or a heavier piston at a lower speed. The next step up would be the H-beam, which can take whatever you can afford to throw at it. Chances are, though, if you are building an engine that requires an H-beam rod, the pistons will be lighter, allowing more rpm and more rod longevity.

Pistons

Much ado is made about forged pistons, which are stronger than cast ones, but unless you're running a power-adder of some sort, your stock pistons will probably survive life inside a street engine. If you're looking for more compression, there are good, inexpensive cast and hypereutectic pistons available in the aftermarket. Go with your machinist's recommendation.

Coatings on pistons can be a good idea for a street engine. Coating on other parts is just a luxury and is probably money better spent elsewhere.

Coatings on pistons can be a good idea for a street engine. Coating on other parts is just a luxury and is probably money better spent elsewhere.

Most factory replacement pistons come with 5/64, 5/64, and 3/16 rings. Aftermarket pistons are made for 1/16, 1/16, and 3/16 rings. They are thinner and offer less friction than the 5/64 rings but are slightly less durable. The piston manufacturer will usually determine the type of ring you should use.

Coatings

As technologies advance, there are a lot of new high-temperature and low-friction coatings available for engine components, the benefits of which are mostly realized in race applications. Johnson says pistons with friction coating in their skirts are useful and can offset some wear in the cylinders over the life of the engine. But coated bearings can probably be passed over by the budget builder. "They're a safety factor, not a power gain," Johnson says. "A bearing is a spacer and should never make contact with the parts it fits between. If you do get contact, the coating will give you a little extra margin of safety before the part fails." The point is, you shouldn't be making contact in the first place, and you have bigger problems than coated bearings will solve.