Tired of the same engine in every Rodney? How's this for different? It's a 331-inch Chrysler "semi-Hemi" that packs a punch both visually and viscerally. The Mopar polysphere engines are a little hard to find, and speed equipment even tougher, but these engines will get you noticed.

Tired of the same engine in every Rodney? How's this for different? It's a 331-inch Chrysler "semi-Hemi" that packs a punch both visually and viscerally. The Mopar polysphere engines are a little hard to find, and speed equipment even tougher, but these engines will get you noticed.

It's encouraging for the future of street rodding that vintage engines have really come into their own lately, serving to spice up the mix and end the boredom of new crate motors in every engine bay-even in cars otherwise built to appear "period."

It does seem a little incongruous when you see a nicely done traditional rod powered by the ubiquitous just-out-of-the-box SBC. Of course they're powerful, stone reliable, and carry a factory warranty, but just when did real hot rodders start becoming as conservative as accountants or actuaries? Even dressed up with vintage-look finned goodies, these engines lack some of the reckless spirit of the 1940s, '50s, or '60s we're wistfully trying to emulate. What need is there for a no-brainer crate motor if your street rod is never going to see more than a few thousand miles a year, or worse, travel safely cocooned on or in a tr%#ler (such a dirty word).

The century we exited just eight years ago was the "century of the automobile," and the Big Three automakers built an astonishing array of engines during those decades. Some were destined for short runs, others were continually improved to stay in Detroit's accelerating technology race, but one fact remains true of just about all engines from the Model T banger onward: They were used and abused by tinkerers, hot rodders, and racers.

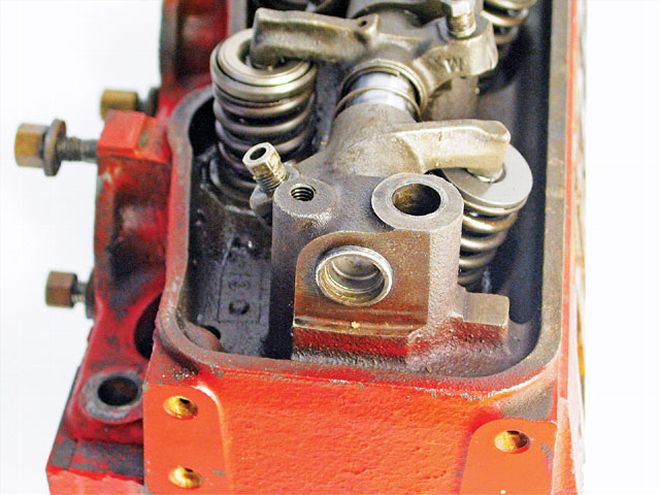

Here's a vintage polysphere in its original environment-in this case, a restored '55 Chrysler Windsor model, where the polys saved the corporation money versus the dual-rocker-shaft/machined-chamber Hemis in the higher-model versions of Chryslers, Dodges, Plymouths, and DeSotos.

Here's a vintage polysphere in its original environment-in this case, a restored '55 Chrysler Windsor model, where the polys saved the corporation money versus the dual-rocker-shaft/machined-chamber Hemis in the higher-model versions of Chryslers, Dodges, Plymouths, and DeSotos.

If you want to know why useable early Ford closed-drive rearends are hard to find, it's because the early rodders banged them into oblivion (and the Zephyr-geared '39 boxes, too) by bolting a wide variety of hotter and bigger engines into the cheap-and-light Fords that formed the basis for hot rodding and racing back then. Oldsmobiles, Buicks, Cadillacs, Chevys, Y-block Fords, and even Studebaker V-8s all served the need for speed. Hot-rodded inlines like Chevy/GMC sixes and NASCAR-winning Hudsons also proved their mettle in street/track racing. Ak Miller was snubbed by his Flathead compadres when he switched camps and stuffed a Buick OHV straight-eight into his Deuce roadster. The naysayers had to eat crow when ol' Ak pruned them all off with the 320-inch Buick, running 118 mph his first time out with it at El Mirage!

What's our point here? Just that there are a lot more engine choices out there than what you'll find in a catalog-engines that are different, and not different in the sense that you have to "dare" to use them, either. Virtually any vintage engine can be rebuilt and hopped up to be as powerful and reliable as you'll ever need in your street rod. When you combine those attributes with the "period cool factor" only a historic powerplant can provide, what's holding you back?

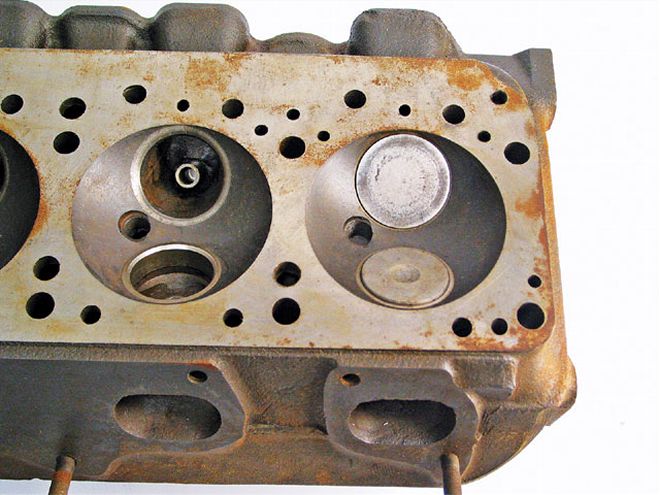

Compare the combustion chambers of the early Hemi (above) and the early polysphere heads. The poly chambers are cast and carry a shape that is the "missing link" between early Hemi and later wedge Mopar chambers.

Compare the combustion chambers of the early Hemi (above) and the early polysphere heads. The poly chambers are cast and carry a shape that is the "missing link" between early Hemi and later wedge Mopar chambers.

We're going to be examining a number of the vintage engine choices out there, specifically the "obsolete" ones that haven't been available for many years. A '57 283 Chevy may be a vintage engine, but it's far from obsolete. Parts or speed equipment for a small-block Chevy are everywhere you step. Some vintage engines, such as the Chrysler Hemi and the Flathead Ford, are so popular today, so well covered in books and magazine articles, and the subject of so much brand-new equipment that we aren't including them in this series.

We'll be looking at the history, performance, and specs of a number of engines, with tips on current sources for rebuilding and hopping them. Our first engine is the "polysphere" found in a number of '50s cars from Chrysler, Dodge, Plymouth, and DeSoto.

The Polysphere V-8S

The postwar period in automotive history found the Detroit automakers playing catch-up, trying to convert from producing war materials back to the civilian vehicles that were their stock in trade. Until 1949, the postwar cars were pretty much slight revisions of the '41 and '42 models, but once that corner was turned and production was in full swing, the engineers and designers were back trying to win in the combat of the marketplace.

While Ford went for a new chassis and very new styling, it still had the venerable Flathead for power, while GM and Chrysler forged ahead with radical new overhead-valve V-8s that started the "horsepower war" that continued throughout the 1950s and on until the "horsepower crash" of the 1970s.

The Hemi made a big splash right from its introduction in '51 Chryslers, and later in Dodge and DeSoto models. As good as their panache and performance were, the Hemi heads were expensive to produce and Chrysler sought a way to make a less-costly version of these engines to keep up production and profits after all the research money they had invested. The misunderstood polysphere engines were the answer. The Hemi owed a great deal of its potential to the half-ball shape of its combustion chamber, the even flame front with the central location of the spark plugs in the chamber, and the port routing allowed by that spark plug placement. Dual rocker shafts (one intake, one exhaust on each head) were required to operate the valves. In order to reduce the production costs, all of these aspects of the Hemi were discarded in favor of more conventional heads on the polysphere engines. The moniker polysphere refers, as does hemisphere, to the shape of the combustion chamber, with the poly chamber more like two half-ball shapes than the single half-ball of the Hemi. The poly engines used a single rocker shaft on each head and the spark plugs were "outside," between the valve covers and the exhaust manifolds. They were sometimes referred to in factory literature or manuals as the "SRS" engine, for single rocker shaft. Although they had as-cast combustion chambers compared to the fully machined chambers in the Hemi head, they were still quite efficient engines and, were they not constantly compared to the Hemi, would be remembered today as decent engines.

As it is, the polysphere engines used in Chrysler, Dodge, Plymouth, and DeSoto models are shrouded more in mystery than in performance legend. All Detroit automakers have their legions of rabid one-marque-forever followers, but the Mopar enthusiasts are in a class by themselves. No other group is so loyal to a fault; they put the fanatic in fan (and we mean that in a nice way). You have to be dedicated to deal with the million little idiosyncrasies of the Mopar brands, and the poly motors are one reason a lot of Mopar fans relate to the '60s cars more than those of the 1950s. Numerous Web discussion groups argue back and forth about the confusion of model years, part numbers, applications, and nomenclature.

Even on those polys that rode on a complete Hemi short-block, the poly pistons had to be different (above) to clear the offset arrangement of the valves compared to the Hemi (below).

Even on those polys that rode on a complete Hemi short-block, the poly pistons had to be different (above) to clear the offset arrangement of the valves compared to the Hemi (below).

The original Hemi was only in production from 1951-58, but the original poly variants were used for an even shorter period, 1955-58. We say variants because the polys used in the lower-line Chrysler models (Windsor and Saratoga) and the Dodge polys were built differently from the poly engines used in the other car lines, in keeping with the crazy variations between the 12 different models of Hemis. The Plymouth line never had its own Hemi in this period, and used polys based on the Dodge engines. From 1956-66, a newer variant of the polys was developed that was even less expensive to produce, and these are called the "A" engines. The confusion comes in when new '67-and-later non-poly engines were also called A engines. Most people decided to call that last group the "LA" series, for "late A" or "light A," adding to the mystery. We're told poly engines were used as late as the late 1960s in Canadian applications, overlapping with the "other" 318 engines. Poly engines were also used in many Dodge trucks (Power Wagons) of the 1956-66 period, even after most passenger-car use had ended. Their decent low-end torque worked well with low-geared applications, and they even did duty in some early motorhomes.

Even on those polys that rode on a complete Hemi short-block, the poly pistons had to be different (above) to clear the offset arrangement of the valves compared to the Hemi (below).

Even on those polys that rode on a complete Hemi short-block, the poly pistons had to be different (above) to clear the offset arrangement of the valves compared to the Hemi (below).

There are several terms thrown about concerning the polysphere blocks, such as low-deck and high-deck (terms also used in describing Hemi variations), but the '50s poly blocks were actually all of the same height/width. It was the variation in cylinder heads that made some appear taller or wider. The polysphere is often fondly called the "semi-Hemi" by its supporters, and it's an appropriate label in some ways. In the Hemi design, the intake and exhaust valves are stacked vertically (looking at the head from the exhaust side), and the pistons for a Hemi have their valve clearance notches similarly aligned. In the polyspheres, the valves are not stacked exactly the same because of the quite different spark plug location, but it is still what we now call a "canted-valve" design. The later LA engines had their valves aligned side by side in a "wedge-shaped" chamber, which became the defacto design for pushrod OHV American engines for the next four decades.

The poly engine was introduced with the '55 Chrysler Windsor in a 301-inch displacement offering 188 hp to those buyers who couldn't step up to the higher-level Chryslers with the Hemi. That same year, in typical Mopar intra-corporate rivalry, Plymouths could be ordered with their own (Dodge-based) 241-inch poly engine, and Dodge offered a 270-inch version. Chrysler lettered its poly engines with "Spitfire" on the valve covers, treading on the cach that name gained in the immediate postwar period when it referred to its most powerful Flathead inline engines. The only branch of the family during the 1950s without its own poly was DeSoto, which used Dodge polys for its lesser models.

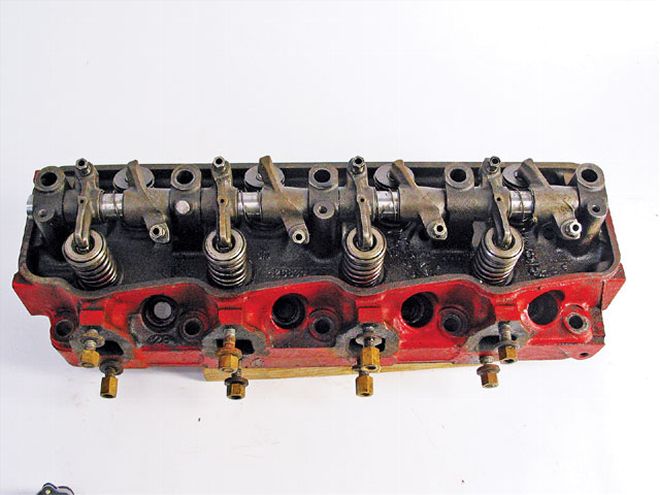

One of the biggest cost-saving factors for Mopar marques using poly engines in the 1950s was the single-rocker-shaft design. The whole head was lighter and smaller than their massive Hemi brothers.

One of the biggest cost-saving factors for Mopar marques using poly engines in the 1950s was the single-rocker-shaft design. The whole head was lighter and smaller than their massive Hemi brothers.

Within the corporation, flagship Chrysler had the most powerful versions of the poly design. It may have been designed to save money, but even a Windsor Chrysler had to have more scoot than any Plymouth or Dodge. In 1956, they stroked the Spitfire to 331 inches, then to 354 in 1957, staying at that size for 1958-the last year for these engines in Chryslers. The most powerful motor offered was the optional 310hp version in the '58 Saratoga models. Polys continued in the other brands, with the lineage enlarged to 325 inches and 252 hp in '58 Dodges.

The '55-58 Chrysler and Dodge polysphere engines were "semi-Hemi" in another way. They were actually completely Hemi from the waist down, i.e., a 331 or 354 poly was a 331/354 Hemi with poly pistons and heads. When drag racers learned this in the early days of fuel racing, they could pull one of these polys from the wrecking yard, get back to the track, and slap on their cam, pushrods, race pistons, and ported Hemi heads and be good to go. The same may be the fate of stock polys in the current craze over early Hemis for street rods. Today's trad-rodders are learning what the fuel racers knew back then: Original Hemis in the underbrush are an endangered species, escalating in price all the time. With their value for conversion to collectible Hemis, stock poly motors today might be only a little easier to source out than finding a First Generation Toyota Land Cruiser that still has a Toyota engine!

Although cheaper to produce than two-rockershaft heads like the Hemi, the poly heads still had relatively good breathing and a reputation for durability. This is a 315-inch "A" head.

Although cheaper to produce than two-rockershaft heads like the Hemi, the poly heads still had relatively good breathing and a reputation for durability. This is a 315-inch "A" head.

Poly Potential

If you can find a gem-in-the-rough polysphere engine and you want something really different to power your next project, go right ahead and take "the road less traveled." If you have any Mopar friends, check with them first, since the polys are often replaced with the LA or other later-model engines when those early cars are rebuilt. Someone you know may have their old poly motor tarped up out behind the garage. They're excellent engines, and while parts aren't SBC-easy, all you'll need to rebuild one is available. Gaskets sets, bearings, rings, replacement pistons, and other standard rebuild parts are still offered by vintage engine supply companies such as Egge Machine and Kanter Auto. Any good machine shop can do the boring, honing, balancing, or decking, just as they would for any engine. Your best bet is to pick up the excellent book by SRM Senior Editor Ron Ceridono, The Complete Chrysler Hemi Engine Manual, published by Tex Smith's Hot Rod Library. It's a must for any Hemi fan, of course, but also has a rebuild story on a 318 poly engine, plus lots of history and parts resources.

Outsiders to the Mopar cult may deride the brand for its confusing array of part numbers and applications, but a silver lining there is that Chrysler kept making newer engines that shared many parts with their older ones, so interchangeability is a big help in building up a poly engine. From the later LA engines of 273/318/340/360 displacements, you can use distributors, valve springs, rings, bearings, rods, cranks, some oil pans, fuel and water pumps, and front covers. That also means you can find modern stroker cranks made for the LA engines to retrofit in your earlier A poly. Some of these items involve minor modifications to transfer to the older engines. Do your research first. One of the best bargains in performance ignitions is the Mopar Direct Connection electronic ignition kit (distributor and module), and you can bolt one right onto your poly motor-or your vintage Hemi for that matter, with a slightly longer extension.

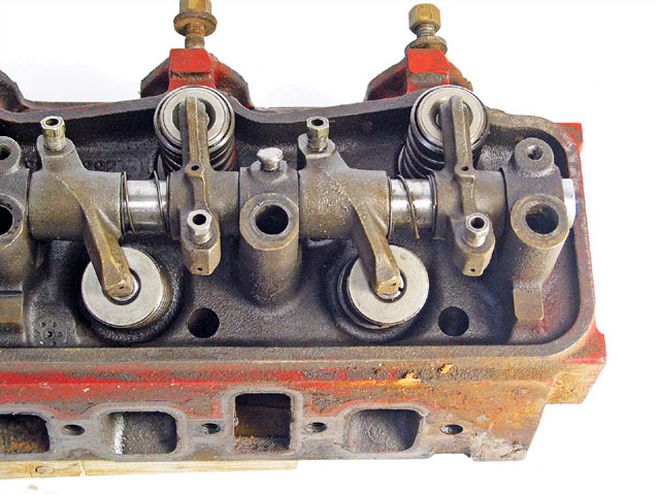

What makes the Hemi head (above) flow so well are the splayed valve angles, which reduce the sharp turns as the ports enter the chamber. Even the poly engine (below) still has some angle on the intake valves. Most wedge motors have valves almost straight up and down versus the block deck.

What makes the Hemi head (above) flow so well are the splayed valve angles, which reduce the sharp turns as the ports enter the chamber. Even the poly engine (below) still has some angle on the intake valves. Most wedge motors have valves almost straight up and down versus the block deck.

Speed equipment for the poly motors is another story. New, long-tube headers are available, but no shorties. Several companies can sell you 3/8-inch-thick flange plates to make your own if you want shorties or outside headers. The intake is the real problem. Back in the day, all the major players in manifolds each had something for the polys (a small market even then), and Weiand had a nice aluminum four-barrel manifold, but discontinued it a few years ago. You'll have to hunt the swaps meets, online discussion groups, and eBay for anything other than a stock two-barrel intake. We don't have room here for all the machinations some poly fans have gone to in adapting other intakes, but one that should be mentioned is using a small-block Ford Windsor or early FE Ford Hilborn intake, since the ports are spaced very close to the poly design. Width across the engine and the flange angle aren't issues for fuel injection, and today shops around the country are converting Hilborns to EFI-an expensive route, but radically cool. If you have an early Dodge poly, things are a little easier, as these engines can use manifolds made for that size Dodge Hemi, and that might be easier to find.

One possibility that has arisen to fill a need in the vintage engine arena is Gear Drive Speed & Custom in Minnesota. Owner Matt Legare makes lakes headers and log-style multi-carb intakes for almost any vintage engine, and also offers the components in kit form for you to weld. Log manifolds are easy to adapt to engines that have a valley cover, and the width variations on engines aren't a problem because the two logs are connected by rubber hoses. You'll have to fabricate a custom valley cover to use log-type intakes on the A polys. You can "make lemonade" out of this seeming drawback by using thick aluminum and have some fins milled in.

You can even get a supercharger kit for the poly from Dick Landy Industries, but you have to supply them with an aluminum intake first, which they set up for a Weiand 174 blower. Cams are available from several old-school grinders like Isky, as well as newschoolers like Nielson Vintage Cams. Stock-compression, cast replacement pistons are readily available, and for more compression, the aftermarket companies have forged blanks that can be machined to whatever you need.

You should be able to easily produce 300 hp out of the larger-displacement poly motors with a little more bore, a little more compression, mild performance cam, headers, and a modern four-barrel intake. These engines already have excellent low-end torque, which in street use is what you really feel in the seat of your Mexican-blanket upholstery, not horsepower. For example, the '58 Dodge 325ci poly developed 355 lb-ft at just 2,800 rpm. Compare that to the Dodge 325 Hemi with 350 lb-ft at a higher 3,200 rpm. The last Chrysler Spitfire, the '58 354-incher, made 385 lb-ft at 2,400 rpm, and that's with a two-barrel carb. Rebuild one of these to stock specifications, add a modern ignition system, full-flow oiling, and adapted spin-on filter setup, side headers, and a four-barrel, and you'll make some Chevys eat your vintage dust.

Transmission availability is an important factor when choosing an alternative powerplant for street rod use. There isn't much to choose from for the poly engines, or the early Hemis for that matter, without the good folks at Wilcap, who produce kits to adapt just about any modern transmission to the poly block. Mopar favorites such as the 727 TorqueFlite can be utilized, as well as GM 350 and 400 THs, plus overdrive automatics. For the three-pedal rodders, there are kits for the Mopar A-883 as well as Ford Top Loaders, Muncie four-speeds, early Ford trannies, Cad-LaSalle vintage trannies, and the modern close-ratio Ford T5 five-speed. The early polys share the same block bolt-pattern and eight-bolt crankshaft flange as all their Hemi brothers (except for the '51-53 "extended-bellhousing" Hemi blocks), so Wilcap has these swaps down to a science.

At this point, you're asking yourself, what's been holding me back from having one of these cool and different motors? We know you've been tortured by the choice between paying dearly for a pre-'58 283 just because it doesn't have side-mounts or spending 10-large to build a 150hp Flathead. Think of a Mopar poly in your rod and the stories you can tell when people ask, "What the hell is that?" Your reply could be a "rare '50s British engine designed for channel-racing boats," or "the last Packard V-8 of the 1950s," or "a Marmon-Herrington OHV conversion for a Flathead." Just be wary of anyone who recognizes it right away. He's apt to be a member of the Mopar cult, and liable to talk your ear off with poly trivia.