If your Poncho suffered from any cooling system problems before storing it for the season, you still have time to address the issues and ensure that overheating becomes a distant memory. For those of you lucky enough to have a top-notch cooling system, maybe it's time to shift your focus to how much additional horsepower can be gained by reducing the parasitic drag of the factory water pump and engine cooling fan.

In Part I of this story, we introduced you to Floyd Hand's '66 Tempest. This 0.030-over 455-equipped car is used for both cruises and heading out to the track to knock down mid-11 second quarter-mile times. After determining that the stock-type cooling system was in need of an upgrade, we took you through the installation of a custom aluminum radiator from Performance Rod and Custom (PRC), a SPAL 16-inch electric fan, Meziere electric water pump and Butler Performance Alternator Relocation kit.

Then in Part II, we tested the effectiveness of the cooling system upgrade and finished up by providing temperature test results that detailed improving cooling system performance for drag racing, around-town driving, and extended highway use. When you are able to drive for 50 highway miles at the posted speeds and maintain 190-degree coolant temps in the Texas heat, you know you have an efficient system. Though a Meziere electric water pump is primarily used by bracket racers, we proved that it was very capable for street and highway driving.

Now that the system has been installed and the basic temperature tests are complete, it's time to find out if there is a horsepower advantage to employing an electric water pump and fan over the factory-based components.

The '66 utilized an OEM-style four-core brass-and-copper radiator with a shroud from a GTO. Equipped with a stock-type iron water pump and 7-blade factory clutch fan, the cooling system was in good working order, but was due for an upgrade.

The '66 utilized an OEM-style four-core brass-and-copper radiator with a shroud from a GTO. Equipped with a stock-type iron water pump and 7-blade factory clutch fan, the cooling system was in good working order, but was due for an upgrade.

Tag along with us to Real Performance Motorsports (RPM) in Lewisville, Texas, as we hunker the Tempest down onto a DynoJet 248 chassis dyno. So confident were we that the installation would be a breeze that our mechanics Floyd Hand and Marty Parker never bothered to ask that the Tempest be unshackled from the dyno to swap components.

The Parts

The baseline setup consists of a stock-style belt-driven iron water pump and a factory 7-blade clutch fan. The hydraulic clutch allows the fan to freewheel and save some horsepower until the fluid heats up to a predetermined temperature. The fan then engages and spins at the same speed as the water pump pulley, via the fan belt. When the temperature drops, the fan once again freewheels. By having to rotate the water pump and fan via the crank pulley and a belt, the engine will be using power to spin the components, thereby reducing the available amount of power that can be transmitted through the driveline and, ultimately, to the rear wheels.

In contrast to the factory parts, the Meziere heavy-duty water pump is electric-powered so the belt that drives a stock-type water pump is completely eliminated. Since the pump is powered by a self-contained electric motor, there's no mechanical power required by the engine to turn it. The same set of factors applies to the SPAL16-inch electric puller fan and the electrical accessories that regulate its operation. By eliminating the engine fan belt and the mass (fan and hydraulic clutch) that the engine must turn to produce enough air for low- and high-speed cooling, there is less parasitic drag.

Testing

Since the basis of the dyno session was to determine any power gains that could be attributed to a reduction in parasitic accessory drag associated with the factory water pump and 7-blade clutch fan, both the original OEM-style setup and the upgraded components had to be tested. To ensure comparable results, both configurations were tested at the same session.

Because the Tempest's upgraded cooling system was already installed, it would have been easier to test it first, then convert back to the OEM-style setup once testing concluded. Rather than test in this order, we instead converted the car back to the stock-type system and had all components of the new system ready to install at the conclusion of the baseline pulls.

To be sure no false readings occurred attributable to differences in the cooling capabilities of the radiators, the new PRC radiator was left in place (minus the factory shroud).

This also provided a force function to ensure that none of the components of the stock system were left behind or went missing. An added bonus was that a stopwatch could be used to time how long it took to swap over the parts without unnecessary delay, such as having to slow down for step-by-step photographs. Since Meziere advertises that its water pump can be "changed in the pits," the challenge was on!

Dyno Results

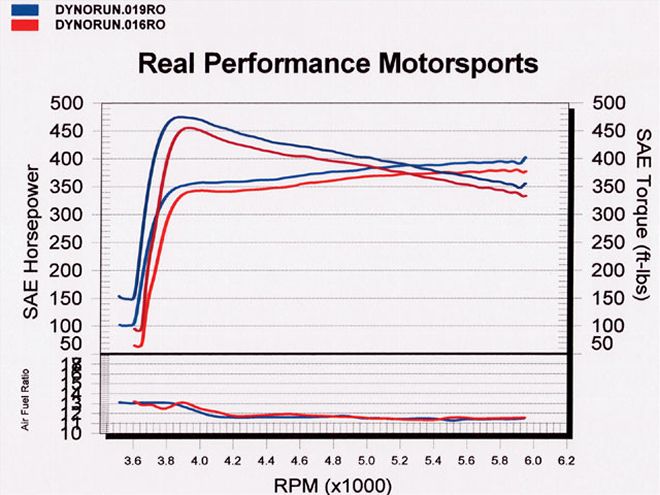

Tests were conducted on a Dynojet 248 chassis dynamometer equipped with a wide-band O2 sensor. All horsepower and torque readings were converted back to SAE. Average horsepower and torque were taken from 3,900-5,900 rpm. In both the baseline- and dyno-tuned configurations, the peak horsepower and torque numbers were recorded at the same rpm levels. Peak horsepower occurred at 5,850 rpm, while peak torque registered at 3,950 rpm. Since the Tempest was equipped with a Turbo 400 automatic transmission and a 3,200 stall tight 10-inch Continental torque converter (Jim Hand Special), the car was pulled in Third gear. Rather than simply romping on it, which caused the car to downshift into Second (and invalidate the dyno pull), the throttle was eased down until just over 3,200 rpm, then mashed to the gunwales.

One glance at the dyno chart is all it takes to notice that the upgraded parts made power all across the rpm band. Note the broad torque and horsepower curves. This torque monster is even more impressive, considering that it runs conservatively-ported iron heads and a hydraulic cam. When converting back to flywheel horsepower, a 20-25 percent factor is generally used for drivetrain losses, putting this Hand-powered engine around 500/600 crankshaft hp/tq.

One glance at the dyno chart is all it takes to notice that the upgraded parts made power all across the rpm band. Note the broad torque and horsepower curves. This torque monster is even more impressive, considering that it runs conservatively-ported iron heads and a hydraulic cam. When converting back to flywheel horsepower, a 20-25 percent factor is generally used for drivetrain losses, putting this Hand-powered engine around 500/600 crankshaft hp/tq.

Conclusion

After testing-of both the OEM-style water pump and fan on the dyno versus the Meziere electric water pump and SPAL 16-inch puller fan-the results were in a word, shocking. While expectations prior to testing were to gain 5-10 hp, a gain of 19 hp at the peak was phenomenal, especially when torque followed right along.

Keith Lohse of RPM states, "Dynos are simply tuning aids that provide relative power and torque gains, and with that in mind, we like to focus on the area under the curve and the averages rather than the absolute peak numbers. Average horsepower and torque are better indicators of real-world gains, and in this case almost 15 hp and 16 lb-ft of torque are impressive. Those types of gains will definitely be felt on the street and should be recordable at the dragstrip."

After sharing the results with David Butler of Butler Performance, he commented, "Our testing on engine dynos consistently shows gains in the 10-15 crankshaft horsepower range. Although the HPP tests showed higher gains, factors such as the brand and relative condition of the water pump and hydraulic clutch fan can definitely make a difference. There is no doubt that the reduction in parasitic drag allows gains. Our customers attest to that on a regular basis."

As time marches on, the OEMs have slowly but surely replaced belt-driven fans with electric fans in order to have less parasitic drag and improve upon their corporate fuel economy standards. Although electric water pumps have not been widely used by the OEMs, it's a pretty safe bet that the decision has more to do with the economics of the parts rather than the efficiency. Let's face it, a cast water pump most likely costs less than an advanced design electric motor such as those found on the Meziere pump. Although costs and fuel economy weigh into the decision-making process of the enthusiast so, too, does the allure of increased power.

If your ride is in need of a cooling system upgrade, there are many avenues to explore. For those enthusiasts who aren't concerned with keeping a "stock-appearing" system, consider checking in with the vendors outlined in "Cool Winds." In addition to significant cooling system performance gains, it's nice to know that you can have your cake and eat at the horsepower trough at the same time.