Back to the Westech dyno we go. This time around we're checking out what gains we might make with the addition of a set of roller rockers from COMP Cams.

Back to the Westech dyno we go. This time around we're checking out what gains we might make with the addition of a set of roller rockers from COMP Cams.

The first two installments of this series touched on the myriad of choices available to us as we build a couple of engine we're doing for upcoming Street Rodder project vehicles, along with how Editor Brennan chose a few affordable, base-model factory small-block crate long-blocks (a 350 from Chevrolet and a 302 from Ford) as the foundations for those project-vehicle powerplants in question.

As we've mentioned, it'd be interesting to chronicle not only what it takes to transform a pair of factory long-block crate assemblies into complete and running engines, but to perform a series of tweaks and upgrades to them using a combination of OEM and aftermarket parts.

This month we're back to our 350-cube Chevy long-block assembly (GM PN 12499529). It's an affordable starting point for a street rod powerplant that delivers a claimed 290 hp @ 5,100 rpm and a solid 326 lb-ft of torque at 3,750 rpm. We initially set it up on Westech Performance's dyno to get some baselines. After a pull or two, Steve Brule of Westech thought it was running a bit fat. He had a jet assortment on hand so he swapped out the stock 72s for a pair of 65s and tried it again. That time it dyno'd (with the smaller jets) at 309.5 hp and 340.2 lb-ft at the aforementioned rpm readings-not too shabby at all.

Another set of baseline pulls was the first step.

Another set of baseline pulls was the first step.

Steve then decided to see what'd happen with a bit of a distributor re-curve, so he swapped out the stock weights and springs for some aftermarket pieces to see what we'd get. The re-curve netted 8 hp and 3 lb-ft of torque (for 317 hp @ 5,100 rpm and 343 lb-ft @ 3,750 rpm). We did one last set of pulls before we wrapped up that first day, swapping out the existing plug wires with a set of solid-core performance wires from Granatelli Motor Sports. The wires netted us an additional 3 hp and 1.9 lb-ft of torque for a total of 320 hp and 344.9 lb-ft total-another respectable gain for little labor and cost.

This time around, we thought we'd see what kind of results we'd get if we swapped out the stock stamped rockers for a set of roller rockers. From what I understand, though conventional rockers get the job done they can do so less than optimally. More often than not, a factory rocker arm's ratio is less than specified. For example, many stock Chevy small-block rockers "check" at between 1.4:1 and 1.47:1, so obviously not all attain the advertised number of 1.5:1. No big deal? Maybe not for a grocery-getter, but it does matter for a performance vehicle. For example, if a camshaft has a lift of .300, multiplying by the advertised rocker ratio of 1.5:1 gives the engine a theoretical valve lift of .450. If the stock rockers only have a ratio of 1.4:1, then the real valve lift is actually .420.

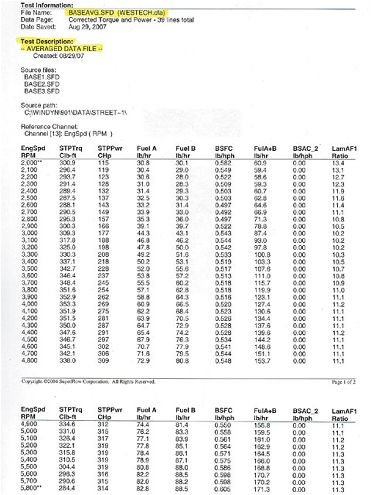

The corrected baseline torque and power numbers for this set of tests (with stock 1.50-ratio stamped rockers) ended up with maximums of 319 hp @ 5,300 rpm and 351.9 lb-ft of torque @ 4,100 rpm.

The corrected baseline torque and power numbers for this set of tests (with stock 1.50-ratio stamped rockers) ended up with maximums of 319 hp @ 5,300 rpm and 351.9 lb-ft of torque @ 4,100 rpm.

You are not only more assured of correct ratios with performance rockers, but you can also play with alternate ratios. Swapping rockers is easier than swapping a cam, and often you can pick up a decent power increase with a simple rocker-arm swap alone.

Aftermarket performance rockers offer improvements over stock. Stamped-steel models might look similar to stock components, but actually aren't. The ratios are held to much tighter tolerances, and typical features include grooved rocker balls along with jam nuts, longer-than-stock slots, and higher-than-stock ratios. Constructed from high-strength steel, aftermarket rockers usually feature more material in the pushrod cup location. Plus, the valve-tip contact surface is often smoother than the corresponding stock mass-produced rockers.

Other benefits of rockers such as COMP Cams' Hi-Tech and Pro Magnum series roller rockers include a stronger-than-stock pushrod cup area. Also, many of these rocker arms have grooves that direct oil from the pushrod to the rocker ball. With a conventional stamped-steel rocker, the tip (the area that contacts the top of the valve) is pushed and dragged across the tip of the valve as the rocker nose is forced down by the camshaft and lifted by the spring. Instead of dragging a steel rocker across the valve tip, the roller rocker rolls over the valve tip. Consequently, wear to both the valve guide and tip's face is reduced.

Once the baselines were completed, Eugene (one of the talented Westech dyno technicians on staff) began swapping out the stock stamped rockers.

Once the baselines were completed, Eugene (one of the talented Westech dyno technicians on staff) began swapping out the stock stamped rockers.

Roller rockers offer another advantage in their pivot or fulcrum area. As engine speed increases, the rockers are cycled at a higher rate. Higher in the rpm range, the rockers are almost always stressed. Lubrication between the rocker arm body and the rocker ball can be less than generous under these conditions in standard stamped rockers; oil is supplied through the pushrod hole but unfortunately not specifically directed to the rocker-ball area.

Some performance roller rockers solve this problem by using roller bearings instead of rocker-ball pivots. A roller bearing produces far less friction and heat than the stock rocker's sliding action. Because of this, oil flow to the topside of the engine can be restricted. Not only does this reduce the overall engine oil temperature, it can help produce more usable horsepower.

There's also a distinct difference when it comes to rocker ratios (the ratio is the distance between the pushrod cup and the rocker's pivot point). A small-block Chevy has a stock theoretical ratio of 1.5:1. If that ratio is modified to 1.6:1, then the gross valve-lift numbers increase without affecting the valve-seat timing, so the advertised duration actually stays the same, but the lift is increases.

In addition to increased lift, a larger-than-stock-ratio rocker also opens the valve quicker and closes the valve slightly later-but there are some possible trade-offs, like spring coil bind. It's also possible that the faster acceleration and deceleration rates produced by high-ratio rockers may produce a certain amount of valvetrain instability at high rpm with stock-rate springs.

With that said, let's get back to the dyno room at Westech and see what happens with our mule. Who knows-there could be some extra horsepower lurking under those valve covers.